Interview with Paul Clipson

By Joel Schlemowitz

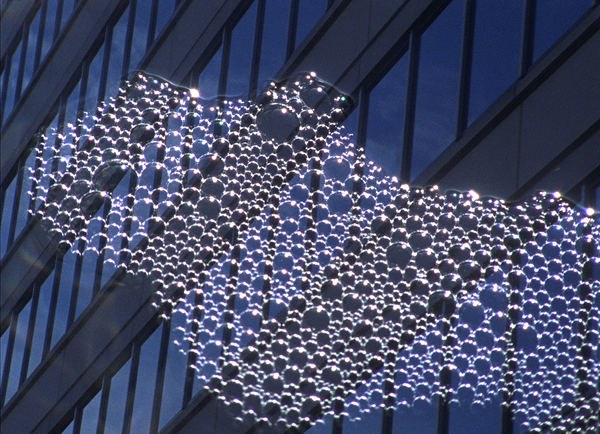

BLACK FIELD / Paul Clipson

BLACK FIELD / Paul Clipson

The death of Paul Clipson in February 2018 was stunning, tragic news. It’s all the more difficult to comprehend when thoughts turn to his films, which are exaltations of the world of the living: the extreme close-up of an insect grasping a spikelet atop wild grass gently shaking in the breeze; the reflections of nocturnal neon in an eye, its lashes like arching cables of a suspension bridge when seen at this perplexingly microscopic scale; a woman, her back to us, walking under heavy clouds, the camera tilting slightly upward to emphasize the dreary beauty of overcast skies; scenes of lights at night again – a symphony of superimposition – with green, red, white, and yellow neon thrown by the camera lens onto the film in multiple layers of patterns and visual counterpoint. The stacked nighttime images are an astonishing achievement considering they are largely created in Super 8 – a format where the film can only be rewound a few seconds at a time, making it quite unsuited to double-exposure! The experience of watching a Paul Clipson film often feels akin in scale and unity to a Franz Liszt symphonic poem – Les Preludes for the eye. Clipson’s films were near-exclusively shown with live music with a sensitivity to the balance of visual and aural, the experience of both together as two sides of a sensory coin, avoiding one becoming reduced to an accompaniment of the other.

This exchange took place in 2014 while Paul was touring his films, arriving in New York, for a screening at Issue Project Room. What had been intended to be a short interview kept going on and I was reluctant to cut the conversation short, intending to edit it down after transcription. But even what seemed a bit off-topic was nonetheless interesting, and so the interesting but too-lengthy interview was set aside for some quiet time when I could give it its due. Now it seems more appropriate to share this interview as a whole – a eulogy to this maker of beloved and beauteous camera-music.

Paul Clipson / Photo: Tony Cross

Paul Clipson / Photo: Tony Cross

Joel Schlemowitz: Can we talk about how you started making films in Super 8?

Paul Clipson: On a certain level some of the films are documentaries about the camera, but I’m never thinking to do an effect because of a concept. It’s more about becoming fascinated with something I’ve become aware of with the camera – like the macro lens or the rack focus, and the feeling that they relate to some sort of consciousness.

I’m completed attuned [with] and wrapped up in narrative cinema. My background is narrative cinema. I’m a film geek. I love films with stories. I love films by Welles, Antonioni, Godard. I don’t see any difference. I don’t see myself as an experimental filmmaker; I just enjoy studying film. I became interested in how when you’re making a narrative, if you have a close-up of somebody and it’s out of focus, obviously that’s terrible. But in a frame there’s always something in focus. Even if it’s all out of focus, it’s just the setting of the lens. Some people think of focus like it’s lost or it’s there. I began to be fascinated with the idea of moving through space with focus, not with the zoom or the camera, but with the focus moving like a wave. Almost like a thought moving, passing over. I was trying to think of environments where there would always be something in focus, because with the Super 8 camera you can focus from the surface of the lens to infinity. CHORUS (2009) is shot in Brooklyn at night, with neon through surfaces, fences, and things, where the focus is moving through the space. [Editor’s Note: Clipson preferred that all his film titles be set in uppercase, citing Bruce Conner as an influence on the matter. A comprehensive filmography of Clipson’s work is available here.] It’s kind of a weird, abstract study – the motivation is this lens. It’s not conceptual, it’s like working with a paintbrush; I’m studying the pull and the tension of mixing different colors. Sometimes the color of the stock chooses the film I’ll make.

All sorts of things grab me, but it’s always from an emotional register. That’s another reason I’m always working with music – I have a very emotional connection to music. SPHINX ON THE SEINE (2008–09) was a way to summarize and reflect on aspects of how I film. The entire film is summoned out of the music. I have this metabolism of wanting to do live shows, and the live shows are an environment, a space. For me to make films I have to have a sense of where they exist. It’s a social process. I never make films just for them to be done – it’s always about showing them somewhere. I don’t watch my films at home. Sometimes I’ve gone to Nick Dorsky’s place and watched a film in his basement, but I don’t have screenings at home. I always do it with a musician and an audience. Very often the experience is the first time for me. So I’m very excited, I don’t know the music, and it’s very intense, even scary. And that reaction is also what I’m trying to do in my films.

SPHINX ON THE SEINE is a crystallization of some of these experiences. I work with people live, like Jefre Cantu-Ledesma, who did the music, who said, “Hey, I’ve been doing some recordings, listen to this.” And I listen to it, and over the course of weeks or months, I hear a piece that summons something. It just has a resonance to me. One of these pieces became SPHINX ON THE SEINE, but it was in the midst of a seventy-minute mediation of music. At first I had the sense of the journey of some train footage I’d shot in St. Petersburg, going to Moscow. And so I put that with the music, and I’m having shivers. Then I didn’t have any more train images, but I tried to relate a sense of movement, of travel, but travel as conscious mental process. I started to look at my other films and find images that related, and slowly it became a kind of poetic sense of rhymes of image, forms, and clusters of tone and texture that related to that music, which itself is very enigmatic. I preserved a sense of letting the images be separate, but like skipping stones over water – how many times could I get it farther out with all these relationships that were completely formal? But the gravity is all within the emotional register of the music, and that’s where that film came from.

I think the films are experiential. That’s where it is. There can be lots of meanings. It’s like having that moment where you’re taking a walk. Walks don’t immediately become transcendent. You could go on a hundred walks and then one of them changes your life. That’s what I want my films to do.

MADE OF AIR / Paul Clipson

MADE OF AIR / Paul Clipson

Schlemowitz: How much of that emotional quality happens in the shooting? Or do you have to wait until the experience of seeing it on the screen?

Clipson: There are streams of work processes. The shorts are crystallizations of a process that’s been happening well beforehand. I feel like everyone has their secrets, their tricks, their cheats, and for me the biggest and most incredible thing is having met musicians because of my work process. I just liked the way they work, a malleable process that is more changing, flexible, loose, and amorphous than filmmaking as I studied it. With narrative you’ve got a script, you’re saving money, you plan, you arrange to meet actors, et cetera. I wanted to get up and shoot in the morning, like a painter or a writer: you get out of bed and you start writing. You don’t think about it and say, “In three months I’m going to shoot a film because I’ll have the budget by then.” I just wanted it to be immediate, and that’s how I saw musicians: they make an album, they work with different people, they play live, and the music changes slowly – you don’t have to play the song the same way.

The live shows where I collaborate are a kind of salon. There’s no finished film. Everybody asks, “What’s the title?” There is no title. I’m just showing rushes – it’s very loose, it’s diaristic, like recording a feeling. When I go out and shoot it’s like recording a musical performance. It’s just like playing a guitar, the repetition and the layers, and getting lost in a walk, and finding things that within months or years of my process I’ve been interested in, like surface reflections. Sometimes I’ve gotten interested in eyes, or nighttime, or insects. Sometimes I think of things to collect at a time when I’m shooting.

I received a commission from the Exploratorium in San Francisco to make a series of surrealist insect films [COMPOUND EYES Nos. 1-5 (2011)]. So there I was focused on a particular subject, but drawing other things towards it, like combining fish with the city at night. But sometimes I’ll be working for months with no design at all, and no end point besides the fact I have shows coming up. The shows are a way of pacing work – it’s given me a drive to work very quickly, and also a looseness and freedom that doesn’t relate to film the way that people normally do, that a film is “finished.” The live shows are just collections of things, and maybe I show the same thing, or just half of it, and by the next show I have new footage and I show half of that. It’s the way music is. So sometimes you’ll see something you’ve seen before, or sometimes you’ll see a totally new thing. I’m always working with different musicians; it’s not like I find one musician and say, “Oh, this is the best, I think I’ll just keep working with them.” In different weeks or months I’ll work with different people, and that influences my filmmaking because I’ll hear rhythms or structural approaches in the use of sound, and absorb those influences.

For me, Orson Welles is one of the greatest experimental filmmakers. The first three minutes of Macbeth (1948) is one of the greatest experimental films. It stands right next to Dog Star Man (1961-64). The witches sequence at the beginning, which is only a minute and a half or so, has all these dissolves. That influenced my films quite dramatically. Bruce Baillie’s Quick Billy (1971) also had a gigantic influence on me. Some of these films were ones that were somewhat late for me to see, and it was like, “Oh this is what I had always wanted.” Sometimes you make what you don’t see, like there must be movies out in the world with all this stuff happening, and after about ten years, you’re like, “Okay, I guess I’ll do some.” And then later, you see Marie Menken, and think, “I’ve been doing films like Marie Menken and I didn’t know it.”

My film UNION (2010) is very influenced by Welles’ Lady From Shanghai (1947). Not that I thought it when I was making it, but when I watched the rushes I wondered, “What is that reminding me of?” And then I saw Welles in the Caligari-esque moments in the funhouse. Welles’ use of camera movement, and the wide-angle lens, and editing, I just don’t see that anywhere else. I don’t see anybody who has carried on with that. Welles is one of those people where I don’t think his discoveries are followed, so I’ve been studying his work. Even if my films don’t look like it, they are echoes of his films. Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point (1970) is my favorite film of all time. I don’t like masterpieces, I’m more interested in films that are doing things. Whether or not they achieve them, I’m fascinated with what the attempt was. Welles was often remembered for what he didn’t do or what wasn’t finished, or how mutilated something was. But when I saw Mr. Arkadin (1955) at the Everyman Cinema in 1985, I staggered out of the film a changed person, absolutely just blown away by it. And that’s a film where he’d likely say, “That was one of the worst experiences of my life.” I think that’s important to remember, because for me, when I’m filming, it’s about battling preconception. When I do performances the planned result is that I want a resonance. But the specificity of what that is, and the meaning of it for each person, myself included, is open. I don’t have any result in mind, because I don’t know what the music will be.

LIGHT YEAR / Paul Clipson

LIGHT YEAR / Paul Clipson

Schlemowitz: Back to the shooting process: all the layers of double-exposures, is that a sort of feeling of not knowing exactly what the result is going to be?

Clipson: When I go out to film, it’s like meditation. Meditation is a struggle against yourself, you’re trying to calm yourself because your faculties are also measuring instruments, and so you’re resistant to calming down because you’re constantly looking and analyzing. I think life and experience is an experimental film. When you’re on a bus, everybody is seeing layers, just as in my films. On a bus at night there are layers going by on the windows, the reflection of people in the window, the reflections of light on the window, there are things going by, neon going by. But most people siphon it out because they’re thinking about the grocery store three stops ahead. They’re looking for that, and don’t see layers because their mind is focused on the aim.

Usually, when people see an experimental film, they think, “Well what does that mean?” And part of it is just letting whatever catches your eye actually catch your eye. When I go out and film, the battle is sometimes that I have an idea – the light has been a certain way, and I want to go to Chinatown because I want to see shadows hitting these old, beautiful buildings where people are shopping in the market, or I want to see light in a hallway, or on a window on the side of a building – so I take the bus, or bike over there and it’s not the way I imagined. I was preconceiving something, and I’m let down and depressed. I wasted an hour coming over here, and the light is falling, it’s almost sunset. I’m going to lose light, and I’ve got to get some work done. So I think I’ll go down to the market because there’s less horizon obscured, some long shadows. I go over there and the sun is already getting obscured by clouds. It just doesn’t look the way I wanted it to look. So now I’ve almost lost the whole day. I’m walking back, and it’s getting dark, and I’m by a huge baseball park, and there is this canal of water, with these old iron-wrought bridges. And as I’m walking by, the sign from the baseball stadium, which is ugliness itself, is reflected in the water and creates the most unbelievably saturated red, an animation of red swirls. I would never have looked at that sign to find that reflection. I was only looking at it because of the despondency of the mental process of trying to find this light through the city. But it brought me to this discovery. And that was from being open, because if I had been too despondent I would have stopped looking.

Everything is recordable, there’s always something. If the light is flat there’s something. If the light is sharp there’s something – it’s your state, it’s your openness to be able to draw from it. That’s the battle I’m talking about. And so the causality and randomness in the films is something like what I just described, this walk where meaning is a struggle of looking and not finding, and then finding.

BLACK FIELD / Paul Clipson

BLACK FIELD / Paul Clipson

Schlemowitz: Something I think about is also the way the camera mediates things – looking for things the way the camera would see them.

Clipson: The whole thing with focus I was describing is that. I started using the macro lens on the Nikon R10, and becoming fascinated by everything it could do. I intuited that this sense of moving the lens to infinity is just this lovely focal spectrum of moving through space. Not moving the camera, not zooming, but moving through focus. And asking myself, could you sustain a whole film by rack focusing and then dissolving at the same time to another rack focus and dissolve? It’s not moving, and the camera isn’t moving, but something is happening. The focus is changing and is a source of movement. I thought it was like a conscious process of moving through space. Maybe that’s thinking through space? I’m not thinking about that too much, I’m not defining it and saying, “Well that means this.” It’s just a starting point. It’s like a random woolgathering: “Okay, that’s enough, I’ll do a film.” Then, what you actually get is these weird congealing of color relations that are registering focus in space. I love the idea of out-of-focus. I love the milkiness. Because when something is in focus after being out of focus there’s a lovely accentuation and exaggeration.

I think the chance element of layers is exactly like drip painting, and the acceptance of gravity as an influence. The choice of color, the choice of gesture, the choice of time, and emotion, the metabolism of letting the paint drip onto the canvas is controlled, but the gravity and the distance is random, and so there’s this looseness. In zooming at neon, and shifting focus, and panning, and reacting, and having only a certain amount of time with an actor or friend to lend their eye, these elements are rewound and layered five or six times over each other with no idea how they’re going to move together, which is very exciting to me. I like that looseness where what I get back is something that I have no idea of what it will look like, although I know the intent, I know what I’ve been doing. It’s more extraordinary to me when I have to ask, “Oh how did that happen?” It’s like I’m the audience member, it’s not like I’m making it as the filmmaker with the idea, I’m watching it as though I didn’t make it. It’s very strange, like a dream.

Schlemowitz: I think that some people might hear “I don’t know what it’s going to look like,” and get the wrong impression. From my own experience, it’s a lot about that balance between anticipating what will happen and not knowing exactly how it will look.

Clipson: I’m a control freak, so it’s exactly that, a mixture. It’s pivoting between an extreme, fixated interest in the study of effects with a lot of interest in exactly how that will come off, and at the same time a loose structure that allows for unexpected qualities. I might have an inkling from bit of footage, and then I work on that specifically to annunciate its qualities. One thing that happened with eyes was that I realized I could just focus on the surface of the eye, and get reflections on the eye, and so I became obsessed with that, and obsessed with the use of the macro lens, and the limpid quality of the colors at night that blend and blur into the softness of the eye. But then the fragility of the surface of the eye has all sorts of associations: Argento and horror films, dreams and nightmares, Buñuel and surrealism, Kubrick’s 2001 (1968). I don’t think of them at the time, but I accept them if they occur to me later. I’m student of film, and I think there are lots of echoes, as I said, without needing to be referential or specific.

Schlemowitz: You had mentioned Bruce Baillie and Marie Menken.

Clipson: I really love Bruce Conner too, because he has a shamanistic, ritualistic aspect but then also references the music video. He uses pop imagery like the atomic bomb explosion, in a pulpy type of way, but then also in an incredibly meditative way, using people like Terry Riley on his soundtracks, and I like that tension. I worked with Bruce in the sense of having the pleasure of being a projectionist of his films at SFMOMA. I saw the films very closely; we did complete retrospectives while he was alive.

Bruce’s use of music was an influence. I like the openness that things don’t have to be completely together. I don’t think it’s important that people understand the work the whole time. I think people are meeting it throughout, and coming out of it. I think that happens with all music and film – it’s about the different times it connects that affect you.

I’ve thought about it a lot with Nick Dorsky’s films, because his films are so studied and silent. Film is an incantation or a spell, you don’t have an epiphany 30 seconds in – maybe it’s eight minutes in, maybe it’s six minutes in, maybe it’s 15. Because of the layers of things within the montage of the cuts, these are triggering things within you as you watch it, and I’m fascinated by watching one of his films that somewhere within 20 minutes – it’s almost like a mediation or a walk – you get hit by it at a certain time.

HYPNOSIS DISPLAY / Paul Clipson

HYPNOSIS DISPLAY / Paul Clipson

With HYPNOSIS DISPLAY (2014), the beginning was very quick – I tried to make it intense right away. But sometimes with my live shows it’s very slow. It’s like a walk where at first it’s all literal and you’re looking at the buildings, and you’re thinking about what you were doing, but then slowly your thoughts about what you were doing earlier in the day start to slowly expand apart, and you pick out details, and then the details start to become abstract. Like an object that was with you earlier in the day, and then that becomes associated with a memory, a building rhymes with the memory. I like that sort of exploration, and I don’t think it happens with everybody at the same pace. And that’s a kind of experimentation for me during the live shows of seeing how my cluster of images, almost like a book where the pages are going by, and images are accumulating, and not all of them are stored because we don’t have the attention to remember every shot, or every movement. It’s like you have a net that’s passing through the images and some of them are collecting associations.

Schlemowitz: Could we talk a bit about the difference in your shooting processes between Super 8 and 16mm?

Clipson: The important thing about Super 8 is the immediacy of it. Godard was trying to get Aaton in the 1980s to make a 35mm camera that could shoot like a Super 8, because he was driving and wanted to shoot sky and the clouds. I think the Super 8 camera is the entire history of the motion picture process in one camera, and all technologies are trying to do that at all times – an iPhone, any video camera. Super 8 is so quick; you can see something and capture it right at that moment. The ending of SPHINX ON THE SEINE is sunlight in a puddle with people walking over it in Moscow, with light diffused by clouds from a rainfall a few minutes before. And the light was like that only for the amount of time I was shooting it. I had no preconception, it was the fact of being near those puddles at the moment I saw them, and it was just because I happened to be there. It’s the end of the film, and I only could do it because of Super 8. The camera and its aptitude, its dexterity, is something I’ve depended upon. Temporally, the camera has allowed me to find things and react with a dexterity because of its quickness. With a 16mm Bolex you have to switch lenses, so if I was switching lenses to get some of the things in SPHINX ON THE SEINE, they would have already left. So the camera is actually defining the world of the film.

There is also a charge to film images. You could say, “Well, why not video?” But I think that film is like an etching, the way that acid is on metal – the feeling of the worth and the loss. I always feel a sense of loss when I’m filming, and it’s a wonderful feeling, because there’s value, there’s a danger of wasted film, and asking, “Will it turn out?” and not knowing what you’re getting. All of that stuff gives me an emotional charge on the surface of the images. The camera is part of that. How quickly it can change focus or zoom, I can zoom quickly within half a second, so to me it’s like sports, it’s like how quickly you can throw a ball. Or like a musician: you don’t think the musical notes, you do the gesture first. When I’m shooting I don’t often frame the image – it’s like learning notes and scales. When Coltrane goes to abstraction, it’s after ten years when he’d been doing ballads and standards. I’ve studied composition, but sometimes I’ll bring the camera up to my eye and film at the moment I see – I don’t stop – because some of the things I see only happen for a moment. In SPHINX ON THE SEINE, there’s a shot of Mt. Fuji from a plane that’s banking over fog, and that’s literally the moment that I looked through the camera that it went by.

Filming for me is like being in a car on a highway. You’re passing by all these things, and in a film like Vertigo (1958), if there’s supposed to be a shot of a tower, it goes by but you’re like, “It looked good, but there was a bump in the highway, so let’s go back and do it again.” And so you go back and do it again, and then think, “Okay, let’s do a third just to make sure.” Well, filmmaking for me is like I’m a passenger, somebody’s driving, I’m looking down, the tower comes by, it’s the most beautiful tower I’ve seen, I’m trying to get the camera out, and the tower is gone. But it’s a six-hour drive, and there’s all these things going on constantly. It’s an acceptance that it’s not what you’re looking for, it’s what you see. It’s a Zen-like acceptance of loss. The films are just an accumulation of things that were permitted to happen because I am working with a process, not because of saying, “I’m making a film about the tower that already went by and I’ve just lost the subject of my film.”

LIGHTHOUSE / Paul Clipson

LIGHTHOUSE / Paul Clipson

Schlemowitz: Of course, with Hitchcock they wouldn’t have even drive by the tower, it would have been a rear projection – so even more artifice, like you say. The thing that strikes me about Super 8 in your work is, on the one hand, the aspect of being unencumbered, but then you’re also going against inherent qualities by rewinding. It’s a struggle against the film cartridge that isn’t designed to do this so easily. So it isn’t a complete submerging of yourself in the medium’s possibilities, maybe “hacking” is not the right word…

Clipson: You mean subverting it, because the cartridge isn’t supposed to go backwards. I didn’t even understand this when I started. It’s been very incremental. I was discovering the camera and the rack focus, and it occurred to me only after years of filming. I realized with the Nikon camera that I could be cutting during a dissolve. Then I asked myself, “Well, what’s going to happen if I’m cutting into a fade, and then I rewind and fade in so the images are overlapping?” But I’m cutting during different shots and don’t even know what some of those shots are, or the order of them, because I’m doing it so quickly. And I found a whole universe just within a dissolve.

These were slow discoveries. The thing about film that nobody talks about, now that everybody’s shooting digital, is that film is so slow. Now I didn’t have an epiphany, but it slowly dawned on me – and it’s what I’d call a philosophical practice – that whenever there is something that doesn’t do something well, if you invert it there is something that it does well because of its malady. What film does very well, if it’s very slow, is that if you’re shooting at night and layer, you can layer ad infinitum. I did not start shooting layers at night with something like six layers. I was trying to get as much light of neon, and I was trying to get dissolves. Then I thought, “If I double expose what’s it going to be? How do I factor that?” And so I thought, “Well, it’s really dark, I’m going to do some double exposures.” I always use automatic exposure on my Super 8 camera. What’s the point of looking at the light meter? That’s the thing about Super 8, it’s built in, so [why not] use everything that it has going for it?

So I just let myself go: I swam further out and realized, “Wait, I can layer some more stuff at night, and I don’t need to care about exposure.” I would get it back and it would be unbelievably saturated, and things would be over each other, and then I just forgot about exposure or how much I should do, and just shoot and rewind. At first I was rewinding long things, and then I thought about how I could do a whole bunch of shots quickly and rewind – it’s only 50 frames – and then shoot some more. And then I realized I could stagger and tile images, and get completely confused. It’s like drawing when you’re crosshatching. As erratic as this way of filming seemed in gesture, the attempt beget beauty. My films are completely about discovering beauty: the beauty of focus, the surface of the screen, the softness and contrast and saturation of the color. So I was layering and forgetting about subject matter and just loving this collaging – letting subject matter come in through just going to spaces outside at night. But more as a container, so that you might have a moment of inspiration or reaction, but not thinking, “How does this define something about the night, or the earth, or the face?” That would not be as experiential.

All the lights in ANOTHER VOID (2012) are beer signs, ATM signs – these things I hate, corporate logos, but it’s all read as out-of-focus light. So I’m using saturation, and it’s changing this world of night that you have to walk around and navigate, some of which is noise and ugliness, trying to make a beautiful, phantasmagorical new experience that could seem drug-induced, but is just a collection of three years of walking through a city compressed into a ten-minute film.

HYPNOSIS DISPLAY / Paul Clipson

HYPNOSIS DISPLAY / Paul Clipson

Schlemowitz: I remember you saying – maybe it was at Projections, at the New York Film Festival – how when you started working in 16mm you had to discover how to do a lot of this all over again.

Clipson: In terms of dexterity and the pace of filming, it was different. The camera is heavier. There’s a grip on the Super 8, and there isn’t on the Bolex. You can get a handgrip, but I don’t have one. So I’m holding the camera differently, the whole movement is different. But I also did new things. I would never use a tripod in Super 8. The first project that lead me to 16mm was LIGHT YEAR (2013). It was a commission and they wanted prints, but I didn’t want to blow up from Super 8. I didn’t feel like I wanted to translate it. My Super 8 films which are on 16mm were blown up by Bill Brand, and he’s fantastic, but at the same time they’re like translations of French surrealist poetry into English. I love them, but it’s not the same thing.

I thought I’ll do a 16mm film because it’ll be a challenge. And the first thing I told myself was, “Don’t just think that now I have to do what I did in Super 8.” So I shot a lot of it with a tripod, and some of HYPNOSIS DISPLAY has a tripod too. With a tripod there was a kind of sweeping, lush movement, which I liked because it was a different trajectory. It helped me get into a state of comfort with using 16mm as itself, not in comparison to anything else. Once I did that, I started to loosen up and stretch further. Then I was able to say, “Okay, now I’ll try appropriating some of those techniques from Super 8.” I also had some chance epiphanies of technical things, like taping lenses onto other lenses, and having amazing effects.

LIGHT YEAR got me practicing in 16mm, and then, in HYPNOSIS DISPLAY, I used 16mm again because of practicality – I couldn’t ensure I would always have a Xenon Super 8 for the screenings [with Liz Harris, a.k.a. Grouper, performing live], so that the image would be bright enough. I travel with a GS1200 Super 8 projector, but there’s a limit to some of the environments it can do with the size of the venue. HYPNOSIS DISPLAY has shown in places with one thousand seats, so it was a logistic issue that created this work in 16mm. I didn’t go to 16mm because I wanted to do better. I think Super 8 is incredible. Now I’m doing a lot of things I was doing in Super 8. I’m enjoying that different weight of the Bolex camera.

Schlemowitz: Is there a difference in your process with work you do on your own versus work that’s commissioned?

Clipson: There’s not a huge difference except a kind of mental awareness. For LIGHT YEAR, I had complete latitude, except that they wanted it to be a study of the waterfront in San Francisco. It was a strict choice of environment, but I could do whatever I wanted to. That helped create focus. HYPNOSIS DISPLAY I found daunting only because they wanted it to be about “America.” And Liz and I both didn’t want to be making statements (although I think her approach was similar, I’m not talking for her), it was about trying to create a metabolic experience of whatever this is, the space, the landscape. The reaction to moving through the space, and if there were associative, thematic, historic, experiential, personal things about America that related to this, I wanted it to be through a metabolic relation, not through a literal history.

I felt like that related to my practice anyway, and I was filming in America and could make the decision to film certain things, but I tried to keep it distant, like a telephoto view. I wasn’t trying to say, “These colors are about America.” So there was a starting point with that subject. It was like getting lost in the forest – you know the parameters, but once you’re in it, there’s this infinitude. The interesting thing about shooting in the forest, like in UNION, was how wherever I reframed the camera there was no relation to what could be seen a slight pivot away, because the design of nature, and leaves, and all of it, is infinite in each frame. When you’re looking at a building or a street, the style of the building relates because it’s man-made. But nature is infinite at each moment of perspective. It’s always changing, so you can only measure it in some geometric process you put over it and say, “That’s a horizon.” But if you reframe and look down only at the water, there is no relation, only the sense of time. Visually, you’re lost. I don’t know how [else] to put it.

MADE OF AIR / Paul Clipson

MADE OF AIR / Paul Clipson

For many years, I was making films and there were no people in them. I think I made a decision to just siphon out things to find a manner in which to shoot. I thought, “Well, if I don’t shoot people, what do I do?” That’s what made me look at things, because I was working to limit myself. When I was shooting without people for a long time I didn’t even think about it after a while – it defined a new kind of way of looking at all kinds of surfaces and spaces, because of that limitation. Occasionally, after a few years, people would say, “Paul, you never have people [in your films].” And I was like, “Yeah, you’re right, I didn’t think about it.” I didn’t necessarily decide not to, I’d forced myself to look at certain things and not look other ways. But when you’re looking at one thing, you’re really studying it, like Monet looking at lily pads or Morandi painting just objects. There’s a lot not there, but then there’s a lot of what’s there there.

But then I thought, “Well, maybe I’ll put some people in.” In SPHINX ON THE SEINE, there is a moment when my girlfriend in Paris appeared on the Seine. That was the only thing I’d shot around that time where there was the silhouette of a woman’s face. Then, at a certain point, I thought of Muybridge and wondered, “What if I could do a whole film-study of a figure? How would that be?” I thought it would be too hard to siphon it into the specificity of just the figure in movement if it was in the city, because there’d be things around it. So then I thought, if the figure was in the forest with a cacophony of surrounding elements, it would be this constancy, and it might allow you to get lost within the forest but also hold onto the figure – to hold onto the figure by focus, by movement, and to define what space is through the figure in it. That changed the gravity and sense of dimensionality, because all the films from five years before it without figures were free of the sense of seeing things in human scale. And that’s how we experience the world.

It became the camera’s experience of the world, with a weight within the frame which I had never felt, and all of the kind of meaning of what a figure is too, because the first thing that happened was that people ascribed meaning and it became a narrative. People said, “That looks like a horror film. She’s being followed.” It’s me following her, but I didn’t think about that.

Schlemowitz: Can we talk about your background in film before you started making these works?

Clipson: I began making films when I was about 15 in Super 8, but very narrative-minded. I didn’t come to what is known as experimental film until the mid-90s, and that’s 20 years later. That’s a lot of time to have been studying narrative, being fascinated with narrative, wanting to make narrative films. That’s kind of why I did HYPNOSIS DISPLAY – it’s like a weird attempt at narrative, but not. I was studying Hitchcock, Godard, Buñuel. I’ve got a huge library of film books. I have original scripts by Jerry Lewis, with the set designs and written stuff on them. I love the history of film. So I did experiments in film when I went to film school.

Schlemowitz: Where was that?

Clipson: University of Michigan. I hated the school, but I loved my fellow students, and U of M and Ann Arbor in the 80s was an incredible film environment. There were four film groups, there was the Michigan Theater, where the Ann Arbor Film Festival still takes place, there were regular first-run films, and even some repertory theaters. For a city of that size it was absolutely fantastic. I did performances at the Ann Arbor Film Festival in 1984, which nobody there remembers. When I went back two years ago for the festival’s 50th anniversary and met Ruth Bradley, who was the director in the 80s and had invited me to perform, she didn’t remember me. But I wasn’t an experimental filmmaker then, it’s like I’m a different person. I was doing a more narrative thing, and I moved to San Francisco, and made some experimental films that are comedy-related – think Beckett, Jacques Tati, and the Lumière Brothers, with Jerry Lewis-style physical comedy. They’re single-takes, nothing like what I do now. But I still really like them.

I started working at SFMOMA as a projectionist, and met Jefre Cantu-Ledesma, who was working there as a technician. I’d never worked the way I do now up until that point. I’d been a student and a monk of film, but I had not been living it. I had been struggling with it – asking myself, “How do I find this process?” I draw, I paint, I do collages and photography, but film I absolutely love. When it ends, that’s fine – it’s a mortality – but I love film. But the question of how to make films I hadn’t solved. I met Jefre and we became friends. He’d done a live show where he’d shown some of Bruce Conner’s films, and I knew Bruce. I wouldn’t say we were friends, but we were friendly – I’d worked with him professionally, and I revere him as an artist. My friend had shown his films on DVD with his own music, and I told him, “You know Bruce would strangle you if he knew you were showing them this way,” because they have their own soundtracks. But then he said, “Well why don’t we do something original with your stuff?”

HYPNOSIS DISPLAY / Paul Clipson

HYPNOSIS DISPLAY / Paul Clipson

I didn’t have films ready for his show. I just took a bunch of stuff I’d shot over time, films shot out trains, towers from a car window, things I liked but never used. They said, “We’ll play around 40 minutes.” So I made an assembly of 40 minutes of random stuff in a way that I think will somehow flow, I go to the show and I project it, and – just like the show I did last night at Issue Project Room – that first show, I feel like it’s the soundtrack to this film. They never looked at the film. I never heard their music before. They’re reacting to each other; there is no connection between the music and the film. Since then I’ve used this process of a sharing between two forms. It taught me there’s no reason to rehearse, or say something like, “Oh when it transitions from daytime footage at 15 minutes in we’re going to transition to drums.” What the point of that? That’s ascribing meaning. I was much more excited by the fact that these things are not connected, and the audience is bridging them. To me the coincidence that we’re in the same room at the same time, that’s very connected right there. People’s reasoning and understanding of sight and sound is the meaning. There is no connection at all – it’s just turning on two things and then people react.

I’ll give you an example. One time there was a film I showed and there were birds in the film. The musicians didn’t know the film, had no experience of the film, and never saw the film. Somebody was playing bird sounds and it was completely by accident. Bird sounds were on while the birds were on. Somebody said afterwards, “Well, that was kind of obvious.” Well yeah, it was obvious, but it wasn’t obvious by intent. I like the disparity.

Schlemowitz: The famous example is Cage and Cunningham’s collaborations, where they created the composition and choreography totally separate from one another. I once heard Robert Breer talking about how he saw picture and sound as two separate things that were autonomous and just happened to be occurring at the same time.

Clipson: Exactly. I do love music scored to film, but this is just another way to do it, that’s all.

Schlemowitz: For Breer, I recall him saying it was his reaction against the sort of “Mickey Mouse” cartoon soundtrack where the sound is too synchronized.

Clipson: Yes, like the birds and the film where it was by chance, but if we had been doing it on purpose I’d hate that.

Schlemowitz: That initial screening experience brought you to this place?

Clipson: That brought me to where I am. And also helped create this practice of mine as a social practice. Seeing how the musicians worked in their daily practice, I found a way to do filmmaking in a more immediate manner. They were doing shows very often, and I was starting to work with different musicians, so I had all these opportunities. I started working faster because I wanted to do this more. If I didn’t have the deadline of a show, I’d be like “Well, I’m going to make a film, and I’ll finish it at the end of the year, or in six months.” But because of the shows it was like, “No, there’s a show in three weeks, I’ve got to shoot some film.” I really liked that, because it didn’t give me enough time to think too much about the film: is it going to be good? Is this different from what I’ve been doing? I didn’t have time to look back, I had to just keep working. Up until that point, which was my late-30s, I had not worked with that sort of structure, at that rate. I became a filmmaker, even though I’ve been making films since I was 15 years old. That was when I was living, breathing it – sometimes getting sick and going too far physically. I realized I had created this space in which I could make films.

BLACK FIELD / Paul Clipson

BLACK FIELD / Paul Clipson

Schlemowitz: I think that energy shows up on the screen: taking the creative process and pushing yourself to move through it.

Clipson: The energy and the excitement, that’s the films. It’s not the technique. The technique is used in practice and is integral, but the experience of the films is the excitement I feel. I’m not premeditating what I want someone else to experience, but I feel if it’s shared, something will be there. When you’re listening to music it affects you, it’s instantaneous. There is no mental process, there is no intellectual trigger that tells you to have an emotional reaction. Only in the recounting does that happen. It sweeps over you as an experience. You suddenly have emotion, and that’s how I like the experience of film to be as well. That’s why I like fragmentation and layers. It starts to impress on you the way that music just passes over you. Because I think in a symphony, or a rock show, or any sort of musical performance, I may be absolutely transfigured, like I’m electrified, but somebody next to me probably is not, because it’s internal. It’s not the same for everybody, and I love the quality of experiencing work. I want to move through that. For film that’s my way of moving through these emotional experiences, navigating through these shots. The shots are this emotional charge, just like the charge of music.

It’s very social, the musicians are important. I would never make a film to finish a film – the film is to be playing, it’s the experience. The film is a mental thing, and you’re in it. Some films are a box and the screen is there; some films there is no screen and you’re in it; and some films are everything outside of the screen. Like with Hitchcock, there’s nothing outside the film – when there’s a close-up, that is the universe. A bottle, a watch, a lighter under a sewer grate. I like that films are defining some weird experiential plane.

TENDERNESS / Paul Clipson

This interview has been lightly edited for flow and clarity by Dan Browne. You can also read Browne’s essay about Clipson’s work on the San Francisco Cinematheque’s website here.

Published June 5, 2018

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Joel Schlemowitz is an experimental filmmaker based in Brooklyn who works in 16mm film, shadowplay, and stereographic media. His first feature film, 78rpm, is an experimental documentary about the gramophone. His short works have been shown at the Ann Arbor Film Festival, New York Film Festival, and Tribeca Film Festival and have received awards from the Chicago Underground Film Festival, The Dallas Video Festival, and elsewhere. Shows of installation artworks include Anthology Film Archives, and Microscope Gallery. He teaches experimental filmmaking at The New School and was the Resident Film Programmer and Arcane Media Specialist at the Morbid Anatomy Museum.