Issue #7/8: Sports

Introduction:

A Non-Zero-Sum Game

By Astria Suparak and Brett Kashmere

For millennia, sports have been intrinsic to daily life, physical well-being, education, civic identity, and social harmony.1 That presence has expanded in the last century to occupy entire sections of newspapers and news hours, in turn begetting 24-hour television channels, talk radio stations, and endless punditry devoted to sports. We contend that over the past decade, sports have assumed an even larger, more multidimensional place in our culture, advancing, for instance, further into the fields of contemporary film, art, and media. This move, facilitated by projects such as ESPN’s prominent 30 for 30 documentary series, the founding of sport film festivals,2 a rise in sports-themed gallery exhibitions,3 and the births of Twitter, sports blogging, and localized, fan-driven websites like those comprising SB Nation, is reflected in the ongoing legitimation of sport within the academy. As Jennifer Hargreaves noted in 1982, although “Sport has traditionally been accorded low academic status in higher education… there has developed an increasing interest in sport as a cultural phenomenon”4 which carries through to today.

Just as sport has been embraced by artists across mediums and genres, so too has it been taken up as an object of study, broadly; traversing physical education, communication studies, the social sciences, and more recently, the humanities. A new academic subfield—critical sport studies—has emerged in response to this swell of cross-disciplinary research. As a result, the traditional schisms, and often times, antagonisms between sports performance and spectatorship, creative production, and scholarly activity (jocks vs nerds, square vs cool), have been blurred. Sports are now readily assimilated into pop culture, celebrity culture, music, and fashion trends. Meanwhile, ancillary aspects of sports have nearly eclipsed the sports themselves. In the information age, fans are the new experts and athletes are objectified as data, becoming sets of statistical profiles and avatars. Sports economies are shifting towards the virtual; the daily fantasy site FanDuel pays out more than $500 million in cash prizes annually, streaming platforms have emerged for live viewing of video game play, and eSports leagues are increasingly lucrative.

Considering these developments, this issue asks: What can the media arts provide sport studies? And conversely, how might theorizations of sport enrich nontraditional approaches to representing and examining athletics? We conceive the relationship as a non-zero-sum game, where both sides (potentially) benefit. Or one that opens a space for productive failures. In the era of instant analysis, flashy data visualization, Twitter journalism, the rumor mill, Insiders, the superfan, and the hot take, experimental media offers a critical tool for addressing deeper meanings, concerns, connections, contradictions, and ideologies. It also provides a set of tactics for unhooking the poetic and aesthetic aspects of sport from the encompassing spectacle.

Why Sports?

This past June the Golden State Warriors won their second National Basketball Association championship in three seasons. Having also set the NBA record for wins last year, the team is enjoying one of the greatest runs in the history of the league. Along the way, the Warriors have revolutionized how the game is conceptualized and played at the highest level, through their embrace of advanced data analytics and privileging of the three-point shot, and by dispensing with the reliance on a traditional center—once the most pivotal position on the court—in favor of small-ball lineups that feature interchangeable players. The long-discussed dream of position-less basketball, where on-court actions are governed by flexible roles and responsibilities instead of predetermined, archetypal tasks (the point guards pass, shooting guards shoot, post players rebound, etc.) has been realized, making the Golden State Warriors a fascinating case study in sports innovation.

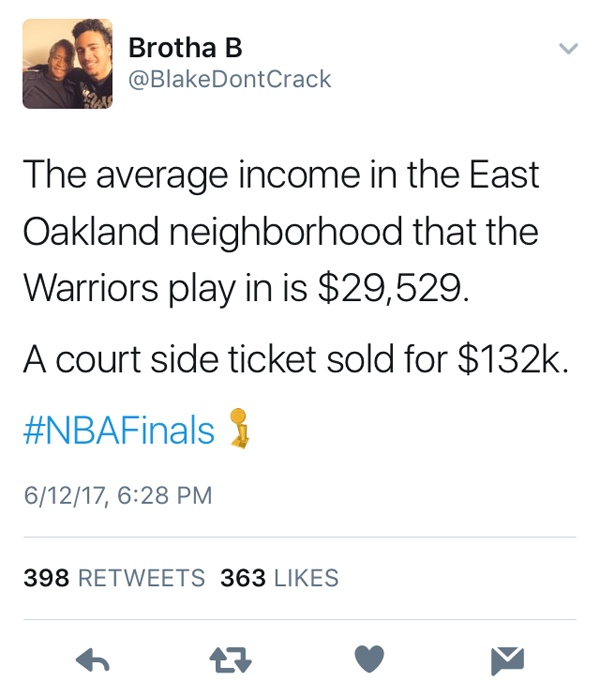

In addition, we have a personal interest. The Warriors reside in Oakland, California, where we’ve been living and working on this issue for the past year. We pass by Oracle Arena, home of the Warriors, on a weekly basis. It’s hard to shake the idea that the current iteration of the Warriors bears a resemblance to Silicon Valley tech businesses, one facet of their present fortunes, which have transformed the Bay Area from a seat of countercultural activity and activism into an upscale, extravagant simulation of its former self. The team is co-owned by Silicon Valley venture capitalist Joe Lacob and Hollywood executive Peter Guber, who together outbid old-school software company Oracle’s CEO Larry Ellison for the team in 2010 with the final price of $450 million dollars. According to Forbes magazine the franchise is now valued at $1.9 billion. Lacob and Guber intend to move the team from East Oakland to San Francisco’s Mission Bay neighborhood, where a new, privately financed, billion-dollar waterfront stadium is being constructed.

Present-day cap (from Bespoke Cut and Sew) referencing both the brief period in which the Warriors basketball team was located in San Francisco (1962-71) and the 1979 cult film of imaginary and outlandish NYC gangs, The Warriors (directed by Walter Hill and based on a 1965 novel by Sol Yurick). Photo: Brett Kashmere.

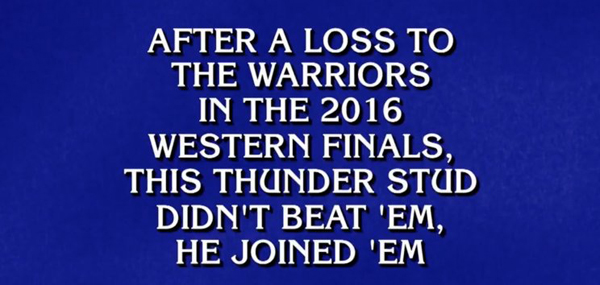

The current version of the Warriors is epitomized by their star player Stephen Curry, a two-time Most Valuable Player. A baby-faced basketball wizard who grew up in NBA arenas, Curry is statistically the best shooter in league history. Steph is the son of Dell Curry, a sharpshooting specialist who played in the NBA for an epically long 16 seasons. (Steph’s brother, Seth, also plays in the NBA.) Steph’s backcourt mate is Klay Thompson, who might be today’s second-best long-range shooter. Klay is the son of Mychal Thompson, a former first overall draft pick in the NBA who also had a lengthy professional career. The Warriors’ third superstar, Kevin Durant, is likewise one of the greatest shooters in league history and a former MVP. He signed with the Warriors before the start of the 2016-17 season, after spending the first seven years of his career with the Oklahoma City Thunder (who relocated from Seattle under questionable circumstances after Durant’s second season, in 2008).5 Many considered Durant’s decision to leave Oklahoma City for Golden State as a free agent to be an act of disloyalty (the teams had been rivals) and a sign of economic and competitive imbalance, with large coastal markets having an upper hand. Although the league has always had super teams, the clustering of this much talent and similar skill-sets on one roster is unprecedented.

“Who is Kevin Durant?” Screen capture of Jeopardy! television broadcast,June 12, 2017. From the internet.

Embedded in these narratives are what draw us to sport—more than the unscripted drama of live competition, or the aesthetic brilliance of elite athletes performing at the height of their abilities, or the bonding in common allegiance with strangers across divisions of gender, race and ethnicity, class, and sexuality. Labor issues, complicated legacies, transactions, personalities, power moves, economics, politics, the impact on ordinary peoples’ lives—these are the dynamics we find most interesting and most in need of closer scrutiny.

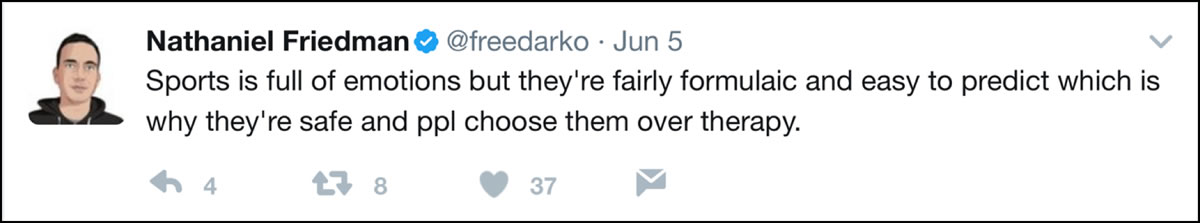

Basketball writer and founder of the influential blog FreeDarko, Nathaniel Friedman, pointed out on Twitter recently:

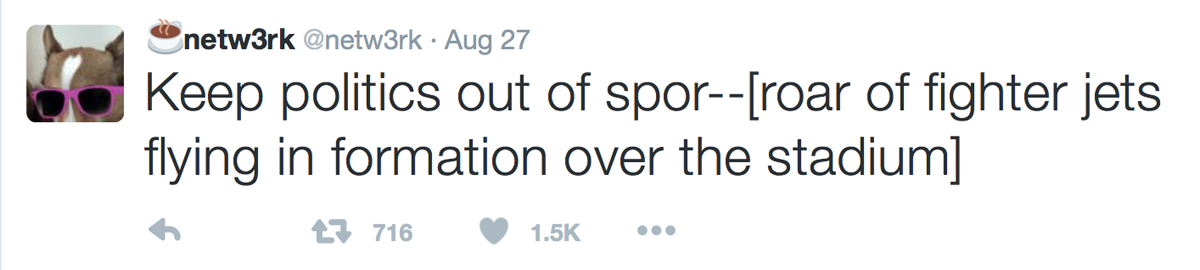

As Friedman suggests, for many, sports are a comfort, providing a temporary haven from political, social, and economic concerns. This is in line with a tradition of writing about sports, mainly from the left, that has considered sport “an opiate of the masses” and a distraction from the more significant aspects of life.6 A prevailing attitude among sports fans and commentators entails that athletes should shut up and play, and that sports should be maintained and treasured as a refuge from politics. This attitude ignores the fact that sports are always already political. Sports are used for political purposes all the time at different scales, and offer an important site of struggle that often goes unrecognized or underreported. Global mega-events like the Olympics are instrumentalized to serve interests such as nation-building and redevelopment. At the municipal level, tax dollars are leveraged by billionaire owners to build new stadiums that sit empty and unused for much of the year. Organizations like professional sports leagues, the International Olympics Committee, and corporate media, what the sociologist Sut Jhally calls the “sports-media complex,” work hard to conceal these political motivations and dealings.

It’s useful here to mobilize cultural critic and public policy consultant Varda Burstyn’s related concept of the “sports nexus,” a web of lucrative “interdependent relationships between the athletic, industrial, and media sectors” that combines cultural and economic influence to generate and assert an elitist, hypermasculine account of power and social order.7 In The Rites of Men: Manhood, Politics, and the Culture of Sports, she convincingly argues that sport is a gendered institution that perpetuates inequality and homophobia. It also reinforces ideas of gender normativity (including humiliating “sex verification” requirements that are woefully out of step with current understandings of gender) and body purity (e.g., the ever-changing set of allowable or punishable drugs and performance-enhancing treatments). Paradoxically, sports can also provide, as author and scholar Julia Bryan-Wilson writes, “a place where such normativity is constantly being discomfited and departed from. Queer and trans-people of course participate widely in sports (so much so, that they have in some instances become a kind of stereotype, as in the paradigmatic dyke softball team).”8 By forging links between manhood, militarism, violence, and the elevation of ever bigger and faster warrior-athletes, Burstyn demonstrates how male dominated, gender-segregated organized sports have become a central factor in how contemporary social and political life is constituted and fortified. Sport is undeniably a hegemonic force, but Burstyn and Bryan-Wilson offer models for how sport can be critically analyzed through a plurality of lenses, including political science, feminist theory, queer theory, disability studies, sociology, economics, infrastructure, cultural studies, and so on.

Why Experimental Media?

Sport films are by and large deeply conservative and conventional. Even when they break from standard approaches they often service hagiographic and/or nationalistic agendas. One sees this as far back as Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia (1938), which harnessed groundbreaking camera and editing techniques in its glorification of fascist Nazi values and able white bodies. And as the film scholar Vivian Sobchack summarizes, “American baseball movies have always seemed connected to questions of nationalism.”9 She notes that the 35 baseball films produced between 1942 and 1989 were released in cycles that closely track America’s involvement in World War II, the Cold War, and the first Gulf War, while only a single American baseball film appeared between 1958 and 1973, a period marked by Vietnam War resistance, civil rights protest, rioting, the rise of second wave feminism, and the integration of professional sports.10 In the United States, the sports film genre, as it has come to be defined through its codes, scholarship, production and broadcast platforms, and dedicated festivals, divides into two categories: Hollywood narratives, like Hoosiers (1986) and White Men Can’t Jump (1992), which often reinforce dominant attitudes and cultural stereotypes while distorting or whitewashing history; and single-topic documentaries, including most of the titles in ESPN’s 30 for 30 catalogue, which focus on exceptional individual players and teams. An apotheosis of the form, O.J.: Made in America (2016) is the exception that proves the rule, offering a micro and macro exploration of modern American life told through the rise and fall of football star turned actor and murderer O.J. Simpson. For all its comprehensive detail and rigor, the movie, formatted as a television series, sticks close to thestandard sports-doc formula (mixing interviews with reenactment and ample archival photo and footage illustration, in a mostly chronological structure). As such, it implies a limit case for what’s possible in documentary mainstream production.

Promotional image for O.J.: Made in America (Ezra Edelman, 2016). From the internet.

Exceptions and antidotes to the modern mainstream sports film can be found by looking to art and experimental media. The paradoxical nature of sport—exhibiting both “manipulative manifestations” and “liberating tendencies”11—is what makes it a rich and fascinating subject, and is why it should be taken seriously as a legitimate area of study, practice, research, and thinking. Art has a role to play in fostering a more comprehensive and critical understanding of sport but thus far has seldom been engaged in the scholarly work of critical sport studies. Adding experimental media into the mix gives more breadth to the potential form an analysis of mediated sports might take while also opening the work up to new audiences and potentials for exchange between theory and practice.

The queer theorist, art critic, and sportswriter Jennifer Doyle describes an “athletic turn” in contemporary art and performance, which we have noticed as well.12 Some of today’s most powerful and insightful critiques on sport and its media is taking place within the realms of experimental film, artists’ cinema, video art, and moving image installation. By engaging a diversity of approaches and perspectives, this issue of INCITE seeks to address some of the unseen political and economic flows of the sports-media complex and the sports nexus. The pieces that follow provide reevaluations of the lines distinguishing sport and game; historical contextualization of professional sport as a locus of pop culture imagery and attention; a partial genealogy of the convergences between sports media and experimental media; and a survey of examples from the recent athletic turn in art, focused mainly on moving image work. Debunking the conventional wisdom that the worlds of sport and art are mutually exclusive, many of the contributors write from a position immersed in sports culture and critically aware fandom. Some are athletes, or used to be. Our goal is to bring spectator sports, play, and experimental media—the corporate/standardized and the individual/deviant—into a productive dialogue, and to consider what kinds of new knowledge might emerge from deconstructions and re-workings of old and new sports imagery, media, and performance.

NOTES

1. As an exhibition currently up at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) notes, “Native peoples across the Americas have played ball games for thousands of years. Many of the games represent ritual battles or echo contests in Native creation stories. Some reenact the struggle between good and evil; others show nonviolent ways to settle disputes. In general, ball games teach social values such as courage, respect, trust, and cooperation.” Emil Her Many Horses, “Ball Games,” wall text, Our Universes: Traditional Knowledge Shapes Our World, National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, D.C., September 2004–September 2020. In a separate display of sports-related ephemera from the NMAI collection, a wall label reads: “Rubber balls are a Native invention. People in Mexico and Central America were making balls out of rubber and playing ballgames more than 3,500 years ago”.

2. For more on this, see Russell Field’s essay “Film Festival Programming and the Cultural Production of Sport” later in the issue.

3. A partial roundup includes: Mixed Signals, a 2009 touring exhibition curated by Christopher Bedford, organized and circulated by Independent Curators International, New York; Hard Targets (a revised version of Mixed Signals), Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio, January 30, 2010–April 11, 2010; Whatever It Takes: Steelers Fan Collections, Rituals, and Obsessions, curated by Jon Rubin and Astria Suparak, Miller Gallery at Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, August 27, 2010–January 30, 2011; Spectator Sports, curated by Allison Grant, Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, April 12–July 3, 2013; Game Changer, curated Ruth Bruno and Cortney Lane Stell, Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art, Boulder, Colorado, July 17–September 14, 2014; Over and Back, curated by Roz Crews and Ryan Woodring, Surplus Space, Portland, Oregon, April 25–May 31, 2015; March Madness, curated by Hank Willis Thomas and Adam Shopkorn, Fort Gansevoort, New York City, March 18–May 1, 2016. A second version of March Madness was organized in spring 2017.

4. Jennifer Hargreaves, “Theorising Sport: An Introduction,” in Sport, Culture and Ideology, ed. Jennifer Hargreaves (London: Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1982), 1.

5. After failing to leverage the city of Seattle into paying for a new $500 million dollar arena, owner Clay Bennett moved the franchise, despite having an arena lease that required the team to play in Seattle through 2010. The Wikipedia page, “Seattle SuperSonics relocation to Oklahoma City,” provides extensive background on the move. See: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seattle_SuperSonics_relocation_to_Oklahoma_City

6. Sut Jhally summarizes this tradition in his essay “Cultural Studies and the Sports/Media Complex,” in Media, Sports, and Society, edited by Lawrence A. Wenner (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1989); see the first section, “The Critical Legacy: Circuses, Opiates, and Ideology,” 70-72.

7. Varda Burstyn, The Rites of Men: Manhood, Politics, and the Culture of Sports (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999), 4.

8. Julia Bryan-Wilson, “Unruliness, Or When Practice Isn’t Perfect,” Mixed Signals: Artists Consider Masculinity in Sports (New York: Independent Curators International, 2009), 60.

9. Vivian Sobchack, “Baseball in the Post-American Cinema, or, Life in the Minor Leagues,” in Out of Bounds: Sports, Media, and the Politics of Identity, edited by Aaron Baker and Todd Boyd (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997), 191.

10. Ibid., 182.

11. Hargreaves, “Theorising Sport,” 23.

12. This is the subject of Doyle’s forthcoming book, The Athletic Turn: Contemporary Art and the Sport Spectacle. Doyle, who formerly published the feminist soccer blog “From a Left Wing” (2007-2013), currently blogs about her research at thesportspectacle.com.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Astria Suparak pledges allegiance to no team, but has curated sports-adjacent exhibitions and programs including Whatever It Takes: Steelers Fan Collections, Rituals, and Obsessions with Jon Rubin at Carnegie Mellon, Elusive Quality with Lauren Cornell at Participant Inc. and The Liverpool Biennial 2004, and the touring program Adolescent boys, and living rooms.

Brett Kashmere is the founding editor and publisher of INCITE.