Interview with Jodie Mack

By Jennifer Stob

Jodie Mack at the Gene Siskel Film Center /Photo: Alex Inglizian

Jodie Mack gleans images from the postmodern plentitude of fabric swatches, magazines, wrapping paper, and the Pennysaver. Her work is strikingly original and impossible to forget, but perhaps also hard to truly see the first time around. I count myself amongst those who needed a repeat viewing in order to fully understand the complexity in her films’ tragicomic lyricism. I assumed a figurative mini-moral piece like Yard Work is Hard Work (2008) was perhaps as visually pleasurable as The Future is Bright (2011), one of her pulsing abstract pattern films, but that their meanings were sealed off from one another. Catching one of the last screenings of Mack’s five-film touring program in October 2014 transformed my thinking on all of her work to date. The program was called “Let Your Light Shine,” and paired four short abstract animation films with a 41-minute experimental musical called Dusty Stacks of Mom: The Poster Project (2013). Dusty Stacks documents the foundering of Mack’s mother’s poster business to the tune of Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon. Mack began touring internationally with “Let Your Light Shine” in the fall of 2013, and it quickly garnered widespread critical acclaim. Her live performance of the lyrics for the songs in Dusty Stacks of Mom was the program’s highlight and the key to the program’s deeper associative logic.

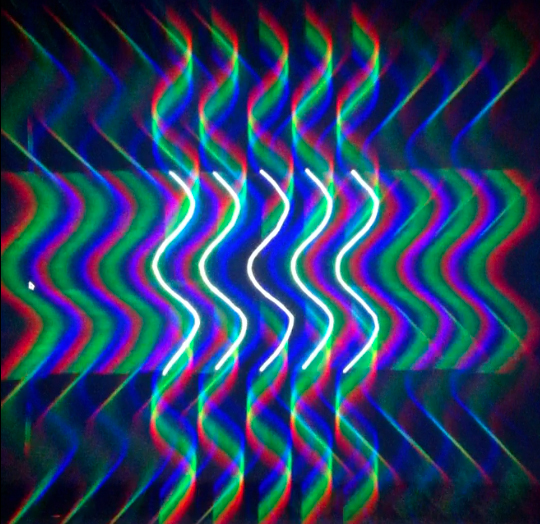

“Let Your Light Shine” was so smartly curated and its individual films so thoughtfully created that it made the interconnectivity of all of Mack’s films clearer to me. As her admirers and detractors both point out, her labor-intensive practice of stop-action animation and her content sourcing from everyday kitsch can be interpreted as a subversion of abstraction’s purism as well as of the long-suffering reverence associated with masculine-dominated avant-garde filmmaking since the late-1960s. However, I believe that “Let Your Light Shine” dialogues less with film art history than her previous work. It does something far more novel and impressive: the labor intensiveness of its process (from material assemblage to film montage to projection to real time musical accompaniment) combines with its subject matter to open up a formal allegory of our 21st century economy. A concept like the “supply chain,” introduced into our vernacular by the tech industry, is humorously and poignantly traced in Dusty Stacks of Mom. The film asks us to contemplate the almost overpowering glut of free images on the Internet replacing the defunct business it eulogizes. New Fancy Foils (2013) rifles systematically through paper sample booklets, themselves foils for the unsystematic archive of contemporary digital images and transformed methods of order placement and fulfillment. Continuing in this vein, Undertone Overture (2013) and Glistening Thrills (2013) could be said to allude to our current societal obsession with scaling, in start-ups as well as in digital imaging: when projected, the tie-dyed fabric and dollar store gift bags in these films are blown up into affective environments. The eponymous final film of “Let Your Light Shine” was a delightful but wistful consumer experience: Mack passed around prismatic glasses so that film-goers could enjoy the illusion of rainbows emanating from the screen and filling the movie theatre.

To allegorize capitalism’s systemic patterns using the patterns of goods themselves was always a goal of Mack’s filmmaking, but “Let Your Light Shine,” presented that goal more lucidly than ever before. It left plenty of room for alternative filmic readings, as well. This spring I had the pleasure of speaking with Mack about her ingenious and gutsy program. We also talked – and laughed – about film sound, the heterogeneous audiences her films bring together, and close-knit and far-flung experimental film communities. We finished with a tantalizing discussion of her plans for another, even more ambitious experimental film musical that focuses on systems of global culture and capital, and that stars alphabets in addition to fabric patterns.

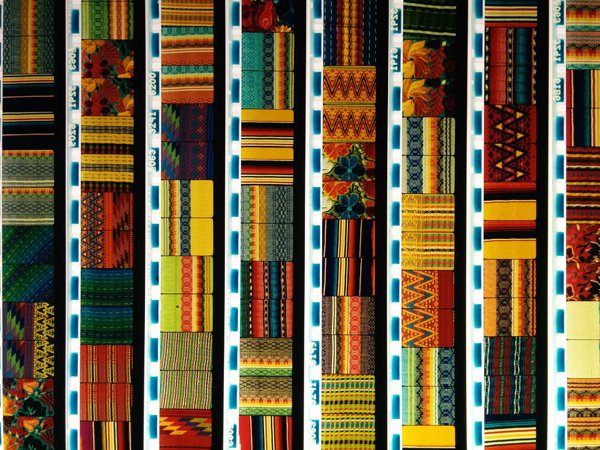

Film strips featuring textiles from Oaxaca / Jodie Mack

Jennifer Stob: Let’s start with your most recent live performance of Dusty Stacks of Mom, in March 2015 at Anthology Film Archives (programmed by Sierra Pettengill and Pacho Velez as a part of their Flaherty NYC 2015 series, That Obscure Object of Desire). What has your experience been with that live component? Will you continue to perform with the film?

Jodie Mack: It's been a big surprise to add this performance component to a screening. I think in general as an experimental filmmaker, you want to be present with your work as much as possible. It's one of the reasons to be an experimental filmmaker: to have that conversation with the audience. But the demands of needing to perform this 40-minute musical composition every couple of days has been strange. For a while, it was great and I felt like I was still really with the work, and it was fun to be with it over and over again. Now, after about a year and a half – a little over a year and a half – of traveling the show around, I'm trying to work on other things. I don't know how often I'll be able to perform with the piece anymore. Being with the piece over and over again and traveling with this kind of show is reminiscent of the origins of both cinema and theatre. For me, cinema's never untied from the theatre, so this performative aspect – allowing a performance to have moments of surprise or unexpected errors – feels vital to me, especially in a culture where we need to stick up for cinema or at least stick up for doing things outside of profit-generating motives. So it’s been all sorts of things; above all, it’s been weird to have this really strange movie, and to put myself out on the line time and time again to all sorts of people with all sorts of attitudes towards what I’m doing.

Stob: You've talked about how this is coming out of an interest in early cinema and mixing cinema with theatre, but you didn’t call it expanded cinema, which is a term that’s really present in experimental filmmaking and experimental film scholarship right now. How important is that term to you, and that you are placed in that framework?

Mack: That’s actually a really good question. Terms, terms. “Expanded cinema,” “experimental cinema.” (Laughter.) I don’t know. I don’t want to criticize the term “expanded cinema” because I think it is important to locate a lot of types of work within that term. But I do want to point out that it doesn’t really acknowledge the cinema’s relationship to theatre or the act of spectatorship with everyone sitting together and looking into this proscenium. Even if we’re actually going to have five or ten screens, we’re still all together sitting in this fixed perspective, watching something. So I think a lot of notions of expanded cinema aren’t even that… you know…

Stob: … expanded?

Mack: It starts to blur. You know, when you’re really expanding it, you’ve almost constricted it again! So I think that term can be a bit slippery. I definitely think that inserting an element of performativity into cinema through notions that could be associated with expanded cinema feels very important – a way of maintaining cinema’s vitality – even though it can also be very cumbersome. One technical element I didn’t mention about the performance is that it’s always a challenge to sing over a karaoke track that’s coming from 16mm. This type of thing almost demands a real traveling roadshow, with the same equipment every time, because it’s not really something that a cinema is designed for. Of course, when you walk into a theater, a space that is quite similar to a cinema, the context shifts completely. Projection is so popular in theatre now that it’s basically the new set design. Expanded cinema isn’t even on the table, you know? It’s just like, “Yes, you’ve put this projector up here, we’re all lighting technician gurus that see it as another element of what constitutes the show.”

Let Your Light Shine / Jodie Mack

Stob: This makes me think of one of the audience questions you got when you toured the show in Austin as a part of Experimental Response Cinema’s fall 2014 line-up: “Are you ever going to do this in a way that people can dance to it?”

Mack: That would be really fun. I did do a screening at the Exploratorium in San Francisco, a museum of science and perception that has an interesting cinema arts program and that locates a lot of experimental film practice within scientific exploration. When I was there in the middle of the day doing this thing for all these families, I tried to make an association between some of the abstract films they were watching and a dance party, and got all of these children up on stage to start writhing around. (Laughter.) I think that’s a great way to think about viewing a lot of this type of work, because it is so inspired by motion. It is a form of dance on its own.

Stob: That’s really interesting. So when you’re making all of your films, there’s a sense in which you’re thinking about bodily movement?

Mack: Yeah, absolutely. I pay a lot of attention to a sense of kinetic energy surrounding me and the way things move, and the way to sort of generate or illustrate the rhythms and feelings associated with many different types of motion. I’m always talking to my classes about how you don’t really need to be able to draw to animate, but you do need to know how to dance. Animation is the manipulation of motion. Time is the other important factor. You need to think of yourself as a practitioner of time: a choreographer of time. Of course in animation, time scientifically orchestrates how certain realistic motions will work based on certain curves of physics, and whatnot. But I’m often thinking of it in a more rhythmic sense, and how temporal rhythms often share a lot of systemic components with patterns – visual patterns – and the construction of fabric itself.

Stob: Over what time period did you make the films in the program, “Let Your Light Shine”?

Mack: Well, I worked on Dusty Stacks from about 2009 to 2013, and then finished the other films in the summer of 2013. While I started Dusty Stacks in 2009, I can’t say that I really worked on it much. I shot about 13 minutes of it and then kind of sat on it for a couple of years and made 12 short little films on the side. Then I went back to it in 2012, and just worked constantly on it every day, every holiday, every spare moment that I had.

Stob: Were you on sabbatical?

Mack: No, I was teaching. Yeah, I don't know how that happened. I just got really inspired with Dusty Stacks. I had all this footage, and I just didn’t know what to do with it for so long. Then, when I had the structural element of the Dark Side of the Moon, I knew how I could send it forward. I went and captured all this material, and I was doing the sound but then realized, “oh, man, sculpting this thing is a whole other element.” After I finished Dusty Stacks, I was like, “I can make a 10-minute abstract film, nooooo problem.” (Laughter.) So Undertone Overture and New Fancy Foils – they just sort of rolled off the tongue. I had a working method for shooting that type of flicker material film, and at that point it was quite easy. Then I wanted to go outside and shoot Glistening Thrills. Let Your Light Shine was just an excuse to work with a film that wanted to be a film. Mixing the soundtrack and getting the soundtrack sandwiched within the optical track range for such a crazy piece was a big challenge, and mixing the sound in general for 16mm is a challenge, so that’s why I wanted to attack the sound that way.

Stob: You’ve got a fabulous voice and it’s clear from your sound design that sound plays an important role in how you make film. Can you talk a little more about that? Did you start out as a musician and found your way to filmmaking?

Mack: I don’t really feel like a musician and honestly, I don’t even feel like singing is something I take as seriously as I want to take it. My formative experiences in art were in being a showman. I was in the musical theatre, so I was singing and dancing and painting sets and doing all sorts of things. Musical theatre is just like live movies, pretty much. I actually went to a magnet high school for performing, and then about two years in, I didn’t like that anymore and changed majors, and started directing.

This experience with singing and dancing again ties into my interest in exploring time for its rhythmic bounty. My first interests were in canonical visual musicians of experimental animation, and when you think about their treatment of sound and time and the way animation functions, it all makes a lot of sense. As I see it, computers then complicated this treatment of image and sound. They actually made it like the introduction of the camera to painting all over again, but with rhythm, because all of a sudden the computer can create this algorithm and make the image move to the sound whereas others had just spent their entire life timing out a Bach piece to make the shapes move. At that point, the integrity of the treatment of time becomes questionable, and so my perspective on sound and my treatment of sound takes sound’s historical relevance to experimental animation into consideration.

There are many rhythmic and musical elements involved in my soundtracks, but with Dusty Stacks, for example, I thought a lot about the role of sound in documentary: how do you convey information in documentary? I thought about the limits of documentary forms as we know them, and how sound plays a role in them. That’s why I decided to sing this documentary. I’ve made another musical, Yard Work is Hard Work (2008),and as I’ve explained I’ve had this interest in musical theatre for a while, so it seemed like an interesting combination. Something that you wouldn’t really consider, and something that really upsets, you know, the hater vibes of audiences in avant-garde film. (Laughter.) I knew this sonic choice was going to be a little uncomfortable, but that to me is the interesting direction to follow. There was a lot of sonic risk-taking within that, and it was very scary.

Stob: So do you think that sound in some sense requires more risk and more vulnerability than composing the image track?

Mack: I think in the particular case of Dusty Stacks, yes. I don’t know about all the time. Definitely saying, “Yeah, I’m just going to sing this to you guys, this experimental film about my mom”: there’s all sorts of no’s going on as far as experimental film is concerned. (Laughter.) So I don't know that it necessarily has more vulnerability than the image for me, but it does sort of unlock the powers of codification within the image, and how those powers can function within a linear temporal trajectory. The relationship there is becoming more and more present to me. That is so important as far as my bigger projects are concerned.

Stob: Since we’re on Dusty Stacks, one of the things that I imagine was part of this vulnerability is the fact that, although there’s this pretty big biographical chunk at the center of the film, it’s not biography. You shift the emphasis to the network or the economy around biography. You must have gotten a lot of questions at these live performances along the lines of "How is your mom? Is she OK?" Hers is a micro-narrative that I think a lot of Americans and probably a lot of people globally relate to because of the economic crisis. I’m curious whether you found it to be a lightening rod for people wanting to emotionally invest in that way.

Dusty Stacks of Mom / Jodie Mack

Mack: Yeah, I think that the story is relatable and a lot of times I’ll sort of correct people: they’ll be like, “well you made this film about your mom” and I’ll be like, “No, it’s not just about my mom, it’s about how this story functions as a result of global capitalism.” I think when bad things happen you have to experience it on that level in some way. “This is my experience, and it’s so awful, yet I’m just this tiny being that is experiencing this along with everyone else experiencing it.” So many people from all over the world have sort of latched on to the micro-narrative of mom within the piece. I thought about that very carefully. During one edit she was sort of all over the piece, but then it became very important to just put her in one or two sections so that other ideas could assert themselves. And yes, there’s a sentimentality within the piece that is of course felt, but was definitely hammed up for this whole “essence of musical theatre documentary with a singing voice-of-god narrator/cabaret griote” or something like that. The great thing about Dusty Stacks is that people that don’t like experimental film really like it because it has that little bit of sentimentality in it; the part that hardcore avant-garde people sort of wince at. But I do want to draw parallels between these two different types of audiences to serve as a mirror for both, and see where these elements that cross over are reflected in each one’s existence.

Stob: Did your mom easily give her consent for participating in Dusty Stacks?

Mack: Yeah, she did.

Stob: What a good mom!

Mack: Yes! And, actually, she wasn’t supposed to be in it at all at first. It was all going to be about the stuff, the materials. There is this moment in Dusty Stacks during the “Time” song that is just all the postcards in alphabetical order. I shot that the first time I went down there. Then I came back and thought, “I want to make this big thing. Or… I could just use this one little part and have it silent… and it would get screened all over the place.” You know what I mean? (Laughter.) When I started shooting that first time, I just took one little shot of her. I also made some voiceover recordings that were terrible, did some interviews, and it was not going well (too predictable!). Naomi Uman saw the shot I had done with her and she said, “I love this shot and this whole element. There’s your story.” Mom was totally fine with it. Yeah, she was great about it.

Stob: The way you’ve described the importance in this period of economic crisis, of seeing oneself as part of something systemic obviously sounds very Marxist to me. I’m assuming theory influences your work, but it’s nothing that you care to spell out and kill a film with. Did your mom see herself in that systemic light?

Mack: I think my work is self-conscious, and yeah, it’s not hitting you over the head but it is sort of implying things here and there through different indicators. I don’t think my mom really thinks about things in those terms. Yeah, she understands that many people are going through this, especially in Florida, because everyone’s jobless and there was a huge housing hit. When she lost her business, other things became a big problem, too. My parents started their business when they were really young and then all of a sudden it was gone, and they didn’t have degrees; they could barely get any type of job. They are immigrants and their Social Security was messed up. So yeah, I think she does understand that. I don't know that she thinks about economic history and political theory. She doesn’t think about art. The nature of my parents’ business fooled me into thinking that they did care about art. When I was younger, I thought they made the posters or designed them, and so I was like, "You guys are artists, right?" and they were like, “No, we’re business people, and we’re basically just the people schlepping this merch around and selling it at the concerts.”

Stob: I read a review of your work by Phil Coldiron in Cinema Scope, and there’s a section in the review that stood out to me. He talks about the “total absence of irony” in your engagement “with things that are generally taken today as tokens of the most frivolous strains of bourgeois culture.” I thought that was off the mark; your work is so ironic. What it’s not is unsentimentally ironic. You’ve got these two audiences, avant-garde film lovers and then a film public without that education or inclination, a larger film festival public. You probably also have a big split in terms of people who do or don’t understand the real sadness in some of your films, and your subtle critique of the materials you use. What’s your take on the fact that you always seem to be working on two or more registers at the same time, and many of your audiences are only getting one, because they’re only looking for one?

Mack: Yeah, that’s true. I think that my films are deceptive on many levels to some people. And they’re deceptive in different ways. Someone might look at some of my fabric flicker films and think that they’re cute or girly or…

Stob: Or straight-out celebratory...

Mack: … or completely celebrating those things, or just another abstract film. I started out making camera-less films, and when I transitioned to making films with the camera, I wanted to approximate the speed of camera-less film motion and bring visual music or abstract animation past their modernist aesthetic origin. I thought, “well, could I make an abstract film with these objects and think about what they actually signify?” That’s what becomes more interesting with each material I work with: they don’t just signify one thing. In my film Persian Pickles (2012), the paisley material is signifying on so many different levels, as an ancient artisanal motif to its appropriated form in psychedelic culture, which is of course linked to the history of experimental animation. I choose to draw from really different places, like musical theatre, head shops, classic rock, and experimental film and force them upon each other, as I said before. That’s what can form something new, but you carry the weight of all of those traditions you’ve drawn from as well. You know, some avant-garde people either hate musical theatre or came up doing musical theatre. (Laughter.)

Stob: I’m thinking about my own love of the super-purist-avant-garde, but also the fact that all of the films I first watched were musicals.

Mack: There’s no denying that the early avant-garde shared a lot of the same impulses with those creating the musical numbers in musicals. The notion of spectacle that was set forth in the musical number creates this whole separate narrative space that doesn’t necessarily need to be a narrative space any more, it could be a dream space or a dance space. That’s something I think about a lot as well: the function of abstraction as a narrative device or a declarative device. The power of declaration was what I was working on in these flicker films.

Because I’m pulling from all of these different elements, you’re right, I don’t think that everyone is getting the full picture all of the time. And I don’t know if that’s a problem or not. I think it can be, but I’m feeling like over the past few years I’ve had the opportunity to speak for myself about a lot of my work, and my work has received critical attention. And, some people have stood up for me and said, “this isn’t just cute.” You know, I do not want to be the Zooey Deschanel of avant-garde film! (Laughter.) You don’t have any choice in how people perceive it once you put it out there anyway, so I’m just happy that it’s rich. You don’t want people to just be so-so on your films. Let them either love them or hate them. If you’re in the middle, then you’re not really hitting anything memorable. I’m coming from a context where having a neighborhood head shop or tie dye t-shirt shop was the closest thing to counterculture growing up. I’m interested in the way that fuels people’s development. Now I’ve been exposed to this universe of people that are like from generations of New England cultural opulence (laughter), and I’m thinking, “Do you guys realize there’s this other world that exists outside of this very niche of a niche of a niche of a niche thing that we’re doing?” I do see experimental film closer to folk art than I do to fine art.

Stob: You mention your New England context or I guess your East Coast context: you live in New Hampshire and are Assistant Professor of Film and Media Studies at Dartmouth College. That makes me wonder about your relationship with this current renaissance of experimental filmmaking that is so exciting to me as an experimental film lover and film-goer. Do you feel a sense of cohort or coalescence? I would also like to hear you talk about your mentors Roger Beebe and Shellie Fleming, as well.

Mack: I think both your questions address a notion of community and how that sort of evolves over time. Just really quick: is there a New England renaissance right now?

Stob: Maybe not New England...

Mack: Or experimental film in general?

Stob: I think so. There are so many youngish experimental filmmakers who are making work that I think is really exciting.

Mack: I get what you’re saying. As far as what’s going on in contemporary experimental filmmaking in general, yeah, I agree, there are so many exciting things to see and experience every time I go to a festival. And there are many inspiring artists out there that are taking the codes and strategies of experimental film of yesteryear and making it relevant for today, and transcending the nitpicking about constantly changing technologies that forces a divide in what we’re doing. Since moving to New England I think my sense of community has definitely shifted, because before that, I was living in Chicago where there’s a very tight-knit sense of experimental film community, and of course it’s bonded by geography and the proximity of everyone in the city. Now my life is definitely a lot more alone time. For a while I felt a sense of absence, but after a few years I realized, “Wow, look at all these new people and experiences that have come into my life this way.” I’ve really benefited from many hours with Cecile Starr – she passed away recently – who is the author of Experimental Animation: Origins of a New Art with Robert Russett. She was there for some of the first Flaherty Film Seminars. I went to her house in Burlington, Vermont to visit her as much as possible, to just absorb knowledge. Someone like Jonathan Schwartz, a filmmaker in Brattleboro, Vermont has become really influential to me. Going back and forth to New York, I have realized that everything is scattered in New England, and that that functions historically: cycles of experimental film history and activity have always flurried through New England.

Cecile Starr riding Mack's bicycle-powered zoetrope / Courtesy of the artist

To get back to your question about Roger Beebe: at University of Florida, and at University of Central Florida as well, where Chris Harris is teaching, for some of the first times you’re seeing undergraduates coming out of these schools with an interest in experimental film. Roger was my teacher at University of Florida. He was very much like I am here at Dartmouth now: active and engaged with the students because there’s not really much else happening here, building all of these great things. We were hungry for it then. I didn’t even have a class with him until my senior year, but I had taken some experimental film classes out in Berkeley the summer before. Then some of us stayed after graduation and started FLEX: The Florida Experimental Film/Video Festival with him, and started meeting all these experimental filmmakers and getting a sense of the experimental film scene at large, so Roger was influential in that.

After undergrad I went to Portland for a few months and interned at a festival, and then attended the SAIC [School of the Art Institute of Chicago], where I worked with Shellie – another great member of the community and someone who also spent her youth in Florida. She was someone who was very maternal with the graduate students and would really encourage you to find your own voice as opposed to putting her voice on your voice. Yard Work is Hard Work is dedicated to Shellie. That was when she fought cancer the first time. We were in communication all the way through some of the final films in the “Let Your Light Shine” program. I had sent her Dusty Stacks. She said to me, “There’s a lot going on here on the superficial level. Have you ever thought of really going down deep?” I think that was an interesting thing to say and an interesting marker of our different generations. Her generation did want to go inwards and mine almost has no choice but to look at things from a wide angle because there are so many things going on.

So yeah, New England. The cycling of experimental film histories. Teachers, and the way they swim around and really color the areas they are in. It’s interesting that there’s this no-man’s-land of experimental film history, and yet all these people did instill and inform my knowledge of film community.

Stob: I would love to see a history of experimental film that highlights the itinerant professors who are spreading the culture.

Mack: Yeah.

Stob: When you were here in Austin, Scott Stark asked you if you think you’re reaching the end of stop-action filmmaking’s potential. You said no.

Mack: I think the beauty of it is that it’s infinite; there are infinite possibilities there. I started out making camera-less films, and when I made films with a camera I wanted to approximate the feeling of camera-less animation. When you’re working so tiny, this stuff has a really fast metabolism because there isn’t registration from frame to frame and there are dots dancing all over the place. I really see a correlation between the camera-less films by people like Stan Brakhage, Len Lye, and Harry Smith. Also the animation of people like Paul Sharits, Paul Glabicki, and Robert Breer: they worked in non-continuous ways that do things to the eyes in similar ways that the camera-less film does. One reason I enjoy animation is that each time you think you’re nearing the end of your range with it you just invent something else. You can back yourself into a corner and get yourself out in a couple of frames. Somebody pointed out that the “Let Your Light Shine” program starts out very flat, and then you get into Glistening Thrills and the depth of real space, and then of course you have the 3D glasses and things coming out at you. I think that the “Let Your Light Shine” program marks this merging fascination with flat, two-dimensional objects, the treatment of light in space, and the treatment of sound on the filmstrip.

Stob: OK, so tell me about what’s up next. I’m intrigued to hear that there is going to be a language component, because it’s obvious from what you’ve written about your films that you’ve got a gift for poetry in addition to working that poetry into images.

Mack: Thank you for your kind words! Well, it was all an accident. Basically, I put in an application to make a film about sarees and their relationship to the landscape of London, where I’m from. Then when I tried to make this film about sarees, it wasn’t really working. I was going to these sarees shops in England being like, “Hi, can I animate with your sarees?” The women were like, “No, these sarees cost a thousand pounds. Get out of here. Do you have a permit?” (Laughter.) One person was like, “OK, go ahead,” and then 10 minutes later they’re like, “Sorry, the boss called, you need to leave.” (Laughter.) It was just not going well. Then my friend Federico Windhausen said, “You need to go to Oaxaca because they have this big fabric tradition and you’re just going to go crazy there.” I met Beto Ruiz, who is a contemporary artist from a family of rug weavers in a whole village of rug weavers, and I shot all this animation at his village for about a week. Then I went to Oaxaca and got more fabric: embroidery and weaving that exemplify a shift from handmade production to industrialized machine production.

Mack filming in Oaxaca, Mexico / Courtesy of the artist

Stob: Trying to keep that cultural cachet despite the shift to mass production...

Mack: But where's the cultural cachet? This is my question. At first this movie was maybe going to deal with Mexican American immigration. I went to Mexico and then I went and shot a bunch of footage in California and it was going to be about that, but then I got invited to China. In China, I went to a fabric district and found all of these samples that were patterned in a similar way as the Mexican rugs. Then I went to Florida, and my friend’s mom has an embroidery company, and she showed me this clip art book of Southwest designs, some of the same that I had found in China. Already in Mexico the question became apparent to me: are these indigenous motifs or did they arrive with Spanish colonization? Did the Spanish get them from Turkey, or Morocco, or India? What’s more important than what they signify is actually what they don't signify. I’m thinking about topologies of codification. My film is going to try to trace the development of fabric production and technology, and map that onto the spread of global capital and the dilution of language. I’m animating charts of alphabets thinking about a shift from pictorial language to the Greco-Roman alphabet, and the way that spoken and written visual languages function as parts of larger systems, just like an embroidery thread.

The outsourcing of fabric production is something that’s going to be a big concern of this movie, as well. In China, everyone was telling me that China is becoming less of a nation of production and more of a nation of consumption. Where is the fabric being produced? India. Where did the motifs I’m looking at come from in the first place? India, I think, or pretty darn close to there. So that’s another interesting element to it.

Mack filming Chinese fabric samples / Courtesy of the artist

Stob: It seems another parallel you’re preparing to make is between fabric and all of the film theoretical debates on whether or not film is a language and whether or not film form can be encoded or deciphered like language can.

Mack: Yes, absolutely. What’s becoming interesting to me is that our desire to communicate really just goes back to this age-old tension between representation and abstraction. You can’t actually abstract something without a notion of representation. All abstract forms are pointing back to nature. I’m also interested in how important sound is in language – Chinese, for example, where you have to sing it. Right now the working title for this is “The Pleasure of the Textile.” (Laughter.) Obviously, I'm not calling it that…

Stob: I don't know. One half of your audience would be very happy. (Laughter.)

Mack: So many people hate puns! Anyway, I’m glad you’re on board with that, but the problem of this movie is the problem of Dusty Stacks is the problem of every movie: how is language going to convey information here? The film is not going to tell its own story; you do need language to get some of these ideas across. I’m thinking I need to go back to hip hop, because hip hop is sonic fabric that has been appropriated in all these different ways. I’m thinking about trying to examine rhythms in the same way I’m examining these alphabets, to see how they've been diluted.

Stob: You’ll resist the impulse to make this film into a documentary?

Mack: This will be a documentary for sure, but it’s going to be a weird one. It might try to interrupt documentary’s codes. One early strategy I had was that each scene could tackle a different problem of documentary – like one scene as cinéma vérité – but we’ve already seen that. So… it needs to be another musical. (Laughter.) I’ve already shot probably about 40 minutes in Mexico, California, Guangzhou – where I did crazy, guerilla-style stop motion animation shooting in the middle of fabric markets – and in Hong Kong. Now I’m going to Argentina in a couple of weeks. I hope to shoot there, but I really feel like I’m just at the beginning of this. I’m also working on another short piece right now that I shot last year while I was traveling. It’s another offshoot of the failed sari project because I obtained a bunch of broken costume jewelry while going from shop to shop, asking to shoot. It’s called Something Between Us. It’s rainbows and diamonds in space, something more lyrical. Just something small to hold me over.

Frame enlargements of Something Between Us (work-in-progress) / Jodie Mack

Published June 4, 2015

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jennifer Stob is a scholar of experimental film and video. Her work focuses on the intersection of contemporary art and moving images, particularly the place of film in the Situationist International and the Austria Filmmakers Cooperative. Her articles have appeared in Evental Aesthetics, Moving Image Review and Art Journal (MIRAJ), and Studies in French Cinema. She is an assistant professor of art history in the School of Art and Design at Texas State University and a co-programmer for Experimental Response Cinema in Austin, Texas.