Interview with Margaret Rorison

By Joel Schlemowitz

As the lights dimmed at the Mono No Aware film event in December 2013, held within the dark and cavernous chamber of LightSpace Studios in Bushwick, Brooklyn, the audience turned their attention to the screen. Extended, low tones of electronic music, performed live, filled the theater. The streaks of light from camera flares, indicating the beginning of a roll of 16mm film, moved across the screen like the opening of a curtain, revealing black-and-white images of dancers clad in white walking together in step through a woodland. In pairs they carried long, gray panels. Later on, with the panels placed upright on the ground, pairs of dancers leaned on either side, pushing and supporting the panel positioned between them. The camera panned across the scene, and the light streaks reappeared as the film roll came to an end. White and yellow flares washed over the screen, indicating a change to color film. In the missing time between the rolls of film the panels had been assembled into a raft, drifting in a river at the bottom of a sloping bank. Two dancers moved together in unison on its deck. Pairs of large, blue plastic barrels acted as floats on either end. The other dancers treaded water beside the floating platform, extending their arms to hang on to the edge of the raft. A subsequent camera roll took us slightly back in time, to the assembling of the raft. The film was PULL/DRIFT (2013) by Margaret Rorison. I found her unthreading the projector just after the film ended, and recall mentioning how every time I saw one of her films I liked her work even more.

In 2012 I saw Rorison’s The Birds of Chernobyl (2012) at Microscope Gallery’s “now what” screening. The film is structured around an elderly male voice heard on the soundtrack, at times clearly and then indistinctly, as the camera moved searchingly through a birch forest. Subsequently, I saw her Gowanus Haze (2012) at the Another Experiment by Women Film Festival. The film meshes the materiality of the gray, hazy, black-and-white 16mm stock with the urban, industrial dereliction of the film’s location. There was a compelling ambiguity to the images. Did the gray dust of Gowanus reflect what we saw on screen, or was the grainy, gray emulsion responsible?

With an opportunity to view more of her films in preparation for this interview, we sat down to talk about her work. The following interview was edited for length and clarity.

PULL/DRIFT / Margaret Rorison

Joel Schlemowitz: I have an interest in camera roll films. Was PULL/DRIFT mostly edited in-camera?

Margaret Rorison: Yes, PULL/DRIFT was, and so was another film of mine, DER SPAZIERGANG (2013). I started to use that as a limitation because film is expensive. I enjoy it, because it also gets me to focus on the moment. With PULL/DRIFT I was documenting a choreographed dance performance, and there wasn’t much time to continuously load film – I had to work with the moment. I’d been watching the Effervescent Dance Collective (who perform in the film) practice throughout the summer, so I could already anticipate the movement of their bodies as I filmed their final performance. I think that you can often create a nice rhythm with in-camera work because you’re so in tune with the direct energy of the moment, you are experiencing the unfolding in real time and so I think the direct response to the charged moment can be captured quite wonderfully. Gowanus Haze too, was mostly in camera. That was my first film. I filmed it while going around on my bike to different locations. I went back to the neighborhood where I lived the summer before I left New York. I biked around and mapped out all the places I needed to have, but I didn’t edit much.

I think there’s a rhythm to looking when you’re shooting in-camera and I think it’s quite natural and intuitive with the Bolex. You have to wind the camera, pause, compose, engage. For me, the camera seems to mimic thought. It’s a direct and simple design: I can focus on what I see without getting caught up in all the variables and options of capturing, like with digital.

I made DER SPAZIERGANG in Berlin. My DSLR (digital still camera) had been stolen in the middle of the night while I was subletting a friend’s studio in Berlin. Some kids broke in and stole my laptop and camera. So, I guess in my mind I desired all these single images of Berlin. There were all these spaces I wanted to remember. I was staying at my friend Sophie Hamacher’s apartment in Tiergarten for a week, while she was on holiday. I borrowed her Bolex and walked and walked and walked, shooting single frames of the city. I liked this rhythm. It was a very different rhythm, different than shooting film with the motor. For the soundtrack, I incorporated field recordings of Berlin and this little beat sequencer, which I had soldered together while in Berlin. I made an electromagnetic pickup, which I used to capture the sound of my 16mm projector and ran that into the beat sequencer, which created this heavier thudding sound. I recorded this all, which became the soundtrack. I see DER SPAZIERGANG as an ode to Berlin and a record of my memories and the materials I discovered there.

JS: What do you think set you on the path towards working with film?

MR: When I was younger, and up until I was 25 or so, I wrote a lot of poetry. My grandfather was a painter, and so is my uncle. I also loved painting and drawing, and getting energy out this way. But I felt limited by painting. I had been painting for just a year or two intensively. I wasn’t really trained; it was an intuitive act. I didn’t know a lot about color theory, or keeping a good, clean palette – my uncle started to show me a bit of that. My paintings were really expressive, lots of movement and I started to ruin them because I didn’t know when to stop. It was then that I began to realize that I needed to work with multiple frames, to explore the progression of time. I felt like poetry was limiting because there was no direct visual element. I thought, okay, I’d really like to work with the moving image. I’m nostalgic, and I like narrating, and telling stories. I played a bit with animation. I did one really small animation, animating some bright tangerine dresses that my mom had made for the play, Into the Woods. I was tentatively going towards the moving image. I also didn’t connect with video the same way. I felt frustrated because working with video meant dealing with codecs and compression rates, glitches, exporting issues… I didn’t have the patience for it at the time.

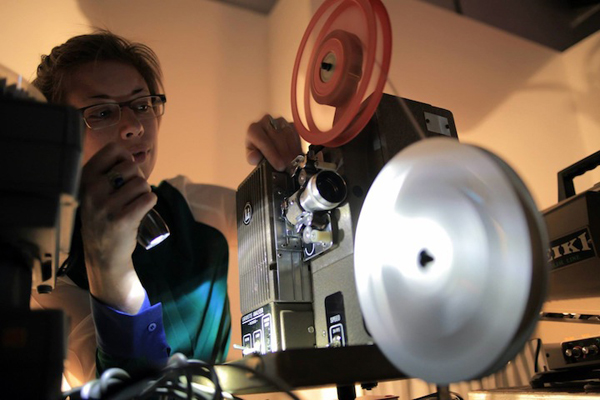

Then I took an introduction to filmmaking class with the documentary photographer, Allen Moore. I got so excited when I was introduced to editing on a Steenbeck. I loved the directness and physical nature of film. It reminded me a lot of painting. From the start, 16mm triggered a lot of excitement. I loved the sound of the projector and the ritual of setting it up, pulling out the arms, and turning on the light beam. It was exciting right from the start.

JS: Where was that class?

MR: It was at MICA [Maryland Institute College of Art]. I originally went there for a one-year, post-baccalaureate program. I’d never gone to art school, and I was painting a lot at the time and wanted the opportunity to work in this type of community, take classes, meet new people, and just make art. It was then that I met, Timothy Druckery. He was the graduate director of MICA’s Photographic and Electronic Media program and was also teaching a seminar called “Crisis Century.” I got along with him really well. He’s a critic and theorist, and a really brilliant guy. I decided I wanted to work with him, and applied to his graduate program. I was still painting but wanted to find a way to further explore the image. That’s when I decided to take Allen Moore’s intro to film class at MICA.

Gowanus Haze / Margaret Rorison

JS: Going back to Gowanus Haze: What was the feeling, or the satisfaction, resulting from that, in terms of then going on to make other work?

MR: Growing up, I always had a journal, and when we went on vacations I often had a disposable camera. I would think about every shot I wanted to get with that camera to perfectly describe my travel experiences. I think I was doing the same thing with that first film. I get really obsessive, and had to get at these certain memories. I had just moved back to Baltimore from New York and I felt really nostalgic. I had to get the energy of that space that I really missed. I think it translated well – I got what I needed. When I watched the footage I didn’t want to do much editing. Later that year, Lea Bertucci got in touch with me; she was doing a mini tour with some musicians from New York, including Josh Millrod, who later did the score for PULL/DRIFT – that’s when I met Josh. They were planning a gig in Baltimore. I was putting on a lot of music shows at the time, so I set up a show for them at my house. Lea asked if I wanted to do something as well, and I thought I would use this as an opportunity to project a film. I was quite nervous – I go to a lot of shows and I have a lot of friends who are musicians, so I really wanted to make a good soundtrack. I spent a lot of time on it, sculpting the sound. Also, I made it without watching the film, and they just sort of married well together.

When I projected it, and people were responding, and they liked it, it made me feel confident about doing this again. I think I was most nervous about the construction. For example, working with a single image, like a painting or a photograph, it can be a lot simpler to come to an understanding of completion or finalization. But I was working to craft a temporal experience that I wanted to be interesting and engaging until the reel ended. After that film I began projecting with other musicians, at music shows and random spaces in Baltimore. One time, I put on a show in the basement of The Red Room. It was really small and narrow, and you had to sit alongside chicken wire and against some old electrical boxes; I projected down the hall. Once I projected over a fire in the backyard onto someone’s house. I always liked activating spaces. But then Lorenzo [Gattorna] said, “Meg, you should submit it as a film to a festival.” So I had to rethink how I would approach that, because up until then, there was a performative nature to projecting the films. They altered with each space and for each performance.

JS: Why don’t we talk a little bit about Sight Unseen?

MR: I guess it got started with meeting Lorenzo Gattorna online. He had just moved to Baltimore with his girlfriend. I noticed that he was an experimental filmmaker. By then I had started putting on experimental film shows in Baltimore but didn’t know many other people who were interested in doing this. So I contacted him; we arranged a meeting and started talking about programming some screenings together. I reached out to this other girl, Kate Ewald, as well. I knew Kate was also in Baltimore because she would often respond to my film-related inquiries on a Google Group called Elfwire, a forum for local artists in Baltimore. Elfwire has since gone downhill, but for a while it was a vital underground space for people to share and exchange equipment and ideas online. There was a lot of incredible discussion happening. I met a lot of friends through this. It was like a virtual coffee house, or meeting space, where people were developing projects. So the three of us met in person, then I found out that MICA was offering these new grants called Launch Artists in Baltimore (LAB Grants) to graduating MFA students. They were large grants, given to graduates to start new projects in Baltimore. It was an incentive for people to stay in the city after graduating. A lot of the time people don’t want to stay in Baltimore; they think it’s too dangerous. That’s changing, but for a while a lot of MICA grad students would just stay in their studio and work and leave after graduation. They never really took time to explore the city.

So, throughout a series of meetings, Lorenzo, Kate and I wrote a proposal for a roaming film series. We proposed a one-year program to begin with. We included letters of support from all of the artists we wanted to show and the different venues where we were planning to do screenings. That’s how it started. We were so enthusiastic, which really drove it for a while. It’s been kind of exhausting though, recently. It’s all-volunteer, and we’re all artists too. And now it’s just Lorenzo and I. We’ve started to work with a few other people. A lot of filmmakers are contacting us to screen. It’s exciting that it’s gotten to that point; there’s a lot of momentum. But we’re also trying to make our own art, and make a living. Lorenzo also wants to go to grad school next year.

JS: You mentioned that Sight Unseen was moving from venue to venue?

MR: There are a lot of venues in Baltimore that are good to project in. Sometime are bars, some are collectively-run spaces. They’re all really different. We liked the idea that depending on the artist, we would choose a particular venue. We're getting to know which ones we really like and which ones have continuous issues. So now we have our favorites. And actually, this Wednesday [October 8, 2014] – Lorenzo programmed it – we’re presenting a screening of a moon films, outdoors. He had to get a permit, but it’s going to be projected on a big wall outside on North Charles and North Avenue, in the center of the newly-named arts district, Station North. It’ll also be a full moon that night. It’ll be really nice.

We’ve liked having a roaming series. It made sense when we started out. But that’s another question we’ve been asking ourselves, if we should think of getting our own space and equipment. Every month we have to find an appropriate space, and we often borrow Allen Moore’s 16mm projector, which has a nice Xenon bulb.

JS: And then there’s that second project, the artist-run lab?

MR: I was in Berlin in 2013 for two months. I wanted to explore, meet new artists, and shoot some film. I reached out to Caspar Stracke, who I met during a talk he gave at MICA, for information about the film community in Berlin. Caspar put me in touch with the experimental filmmaker Sylvia Schedelbauer, who introduced me to Michel Balagué, the founder of the artist-run film lab, LaborBerlin.

JS: Ah yes, LaborBerlin. Juan David González Monroy and Anja Dornieden are there. They used to be at The New School in New York.

MR: Yeah, so in Berlin I was introduced to the notion of the artist-run lab. That following fall, I went with LaborBerlin to a film festival in Colorado [The International Experimental Cinema Exposition], focusing on the artist-run labs. The festival brought in filmmakers from all over the world. I went with LaborBerlin because I was still a member, and we put together a program to show there. That opened up my eyes: I met so many people from labs in France, Croatia, Australia, Canada, Colorado, and Mono No Aware in Brooklyn. I kept thinking about how incredible it would be to have something like that in Baltimore. Then this student, Chris Cheng, who was in the same program at MICA that I was in, was graduating and asked me to help write a proposal for the MICA LAB award, to start a series of filmmaking workshops in Baltimore. I wrote a budget for chemicals and darkroom equipment, and we contacted an artist-run gallery, Current Space, that has a community darkroom to ask if we could use it for the workshops. We got the grant and had the first workshop in July – a hand-made emulsion workshop organized by Kevin Rice and Andrew Busti of Process Reversal Collective.

Current has a sinkhole now, so we had to move the next workshop. It was really stressful, but we found another place. It’s always something. There was another huge sinkhole in Baltimore and a whole street collapsed. I think people are starting to take sinkholes seriously there now. I don’t know what the status is at this moment at Current, but they had to turn off the water. It was in their garage, right under their space.

PULL/DRIFT / Margaret Rorison

JS: How did you connect with the choreographer and dance troupe in PULL/DRIFT? Are they local to Baltimore as well?

MR: Yes. The artist Clarissa Gregory choreographed the dance. I used to live with her boyfriend, now husband, Jimmy Joe Roche. It’s a small community, so we all know each other. She conceived the idea of the choreographed performance in the woods. She’s very organized. She put together the practice schedule and the performance was planned for September. She wanted to have three people whose work focused around nature to document it, to have that as a whole other element of the piece. We all met together, the three documentarians, and realized we all had very different approaches, which worked out nicely for what we wanted to do.

JS: What were the other two approaches?

MR: Liz Donadio wanted to document the performance with a video camera. She ended up layering the images to create an effect of strange disorientation, which was combined with a recorded soundtrack by Rod Hamilton and Tiffany Seal, who did the original sound for the performance. It was more of a video documentation of the work. She also took large photographic portraits of the woods without the performers. Carr Kizzier made black-and-white, hand-processed portraits of all the performers. He also did a video, too.

PULL/DRIFT / Margaret Rorison

JS: Could you tell me a little bit about filming the part where they’re on the raft in PULL/DRIFT?

MR: The performance took place up in the hills and then moved down to the shoreline. The dancers built a raft and floated down the river, with the dance taking place on the raft. Me and the other two artists who were documenting the performance went along with the audience, walking parallel with the river. Once they entered the river we had to move very quickly. I had three different lenses, but I was kind of far away from the performers. I was filming hand-held through the trees, from on the top of the riverbank looking down. I liked the hand-held look with the trees in the foreground. I wasn’t thinking so much about how to approach it; I was more concerned about getting them in frame because they were moving quite fast. It was sort of like when you’re following a cross-country race and you think about the next perspective and where you’ll see the runners. In this case I knew that they would dock the raft, emerge from the woods, and the final performance would take place on this large, grassy area.

The whole time this was happening we were moving along with the audience. It was a performance that anyone could come to see. There were a lot of people who swam in that part of the river. They had seen us practicing for weeks prior, and so we invited them to come that Sunday at 4pm for the final performance. There ended up being a really large audience. Another artist, Graham Coreil-Allen, led this parade of spectators, using flags to guide everyone along the river.

JS: How many people were there watching the performance?

MR: Maybe about seventy.

JS: You wouldn’t know that from the film.

MR: I really didn’t want the audience in the film, because then it would have been a different piece. I just wanted to document the performance and not the whole event with the audience. I wanted it to be more intimate and more focused on the dancers and the landscape.

JS: Can we talk about SCANSION (2012)? A very Baltimore piece, I guess?

MR: SCANSION was the second film I made; it was for my MFA thesis. We had to exhibit in a white-walled gallery, and I really didn’t connect with that type of exhibition. I wanted to find a way to project film in the gallery space so I started looking at loopers. Then someone put me in touch with Kenny Curwood. He showed me a looper he designed and told me how much it would cost. But he also said, “You can build it yourself easily enough, and here’s a PDF that will show you how.” I ended up buying one from him anyway. It was a very simple, beautiful one. That resolved the problem. So I originally made SCANSION as an installation with 5.1 surround sound. It was installed in an old market on North Avenue. This was the first time that MICA was using a new off-campus space for thesis shows. The space I wanted to exhibit in had sloping floors. It was designed that way. They would clean the space by spraying water that would spill down and out of the building. At first MICA didn’t want me to use this back space. It was a mess and was filled with trash. It was quite disgusting. But I just kept insisting that I’d clean it, and that it would be really nice. In the end, I convinced them and I was able to use it.

The space was a long passageway and I put black curtains up along both walls. You would turn the corner and the projector was right there. The film was about nine minutes, and the soundtrack about 12. At the time I was feeling kind of haunted by Baltimore. The landscape was starting to become very emotional for me. I wanted to have a memory of that, and a film about it. A big part of my winter was spent driving through that landscape, the west side of Baltimore, to this part of town that was abandoned and overgrown. There was such a distinct visual language and energy to it. So I started filming and filming. My friend James Singewald, who does large-format photos of historical buildings in Baltimore would tell me, “You should film on Sundays, when people are at church.” I wanted to imagine the landscape without the people. That was also around the time when I was thinking, “We spend so much time in front of our computers, and what would the world be like if we just never left?”

The title came from a handout for Bruce McClure’s piece, Double Pipes: “Scansion also analyses the rhyme scheme in a poem or stanza, giving alphabetical symbols to the rhymes: abcb or abab in most quatrains, aabba in limericks, for instance” (Bruce McClure, program notes for Double Pipes, 2011). I’ve always loved Bruce’s little papers. That word, “scansion,” I really liked. How it refers to scanning poetry, looking for the inherent rhyme, the stressed and unstressed syllables. I felt like that was the act I was performing when I was editing – I used a Steenbeck to edit – and so I was finding the inherent rhythm of the landscape.

But I didn’t have enough money to make another print. I don’t have another copy of this, and it’s so scratched.

JS: But I think the distressed quality of it blends so well with the distressed city. I wouldn’t make another print. Or if you do make another print, then make an internegative from that worn-out workprint. These images of urban decay, seen on a piece of film that feels like it’s suffering from its own version of urban decay.

MR: That’s good to hear.

JS: But I’m curious – watching it I felt like I was entering it as a linear piece. So as an installation piece, playing as a loop, were you very conscious of that method of presentation, as something to work with in the editing structure? Do you feel it can work in both settings, film loop and screening?

MR: I think it’s definitely a linear piece. Looping it was my way to use film for my thesis show. I added a few feet of black leader between the beginning and ending of the film, and I made the soundtrack longer so that there was always some sort of spatialized experience even when the image disappeared. I thought it worked fine, because it’s more of an abstract narrative. But when I edited it, I did think of it as linear.

The Birds of Chernobyl / Margaret Rorison

JS: The Waiting Sands (2013) and The Birds of Chernobyl – are both of those films about your grandfather?

MR: Yes. In Gowanus Haze I used my grandfather’s voice. I’d always liked his voice. He was living with my mom and he had Alzheimer's. I was really deep into beginning to explore filmmaking, and it was a nice thing that I could share with him, because he was an artist. Before we would always talk about drawing and painting, and therefore I still wanted to include him in my creative process. For The Birds of Chernobyl I used his voice as well. I guess it’s about him. That piece is strange. It was made because I’m in this other collective called The Red Room Collective. It focuses more on improvisational, experimental artists; musicians mainly, and performers. It’s a lot like Issue Project Room, when Suzanne Fiol used to run it. Many of the same people who played at Issue would also come through The Red Room. But there are no paid positions; it’s collectively run. We put on a festival every September. If you’re a member of the collective you can perform every other year. So, the collective nominated me to do a solo performance, but I didn’t know what I was going to do because I wasn’t a musician. I’d started mic’ing my 16mm projectors, using contact mics and electromagnetic pickups. I had some footage that I’d shot that summer in the Ozarks. It was just sort of wandering, landscape footage. I thought I’d sculpt the soundtrack live and incorporate my grandfather. He was getting older and sicker. I felt really emotional about him, so I knew he had to be a part of this. When I was in the Ozarks, at this little residency, I was with this other painter, Jeffrey Vincent. He reminded me of my grandfather. One night he was telling me this story about the birds of Chernobyl, about how they sing louder because they can’t find their mate. I thought that was really haunting and beautiful, the idea that in this destroyed landscape you can hear these bird calls, that are even more heightened and more beautiful. Perhaps this was making me think of my grandfather. I was feeling more melancholy and sad around that time in my life. He watched a lot of the footage and narrated a bit in response to it. I was really into using his voice, and getting as much of him as I could.

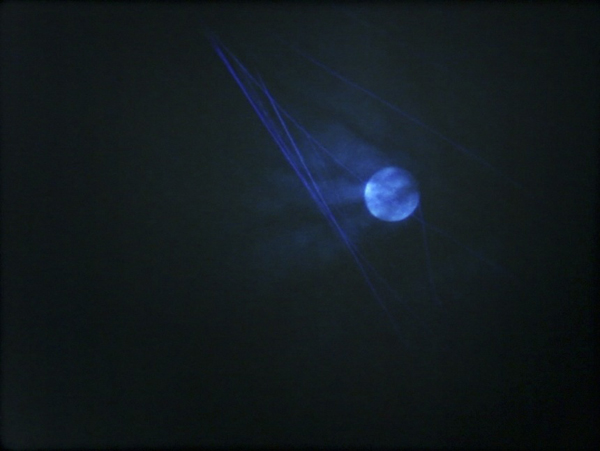

The Waiting Sands / Margaret Rorison

I made The Waiting Sands while he was in the hospital. He was really sick by that time, and I knew he was going to die there. I became consumed by thinking about him, and would go every day to the hospital. I wanted to film him. I don’t have a Bolex, so I borrowed Lorenzo’s. I met Lorenzo one night, and he was like, “Here!” and he gave me a lot of film. I would go to the hospital with my camera, but my grandmother – his wife – didn’t want me to shoot. I felt strange about it, like it was something that I didn’t think I really should do, but that I had to do anyway. One day was feeling very emotional. The film had been loaded in the camera for a few weeks and I needed to do something. During that time, I was staying at my mother’s house to help out. There was a beautiful full moon that night. It was November 28, 2012, the last Harvest Moon of the season. I started filming the moon through the trees. Coincidentally he died that night. I found out the next morning from my mom. He died about three hours after my filming. So I thought of this film as sort of like a documentation of his last breaths, a eulogy. I didn’t edit it at all. I showed the footage to my friend Josh Millrod – who had done the music for PULL/DRIFT – and he made a really beautiful soundtrack for it. I think the sound is a really important, dominant part of it. But the footage is a bit fogged, and there’s some jerky camera movement. Technically I’m not so excited by it. I’m just leaving it at that, as a memory of the moment.

The title, The Waiting Sands, comes from my grandfather’s work as a painter. He did paintings for the covers of romance and gothic novels, as well as illustrations for a translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy. The Waiting Sands is the title of one of the books that he illustrated. I really like that title. The books often have strange stories, and the illustrations that my grandfather did were quite strange as well. A lot of the time the image is of a woman in the foreground, and a man behind her, running after her, and there’s often a moon, or a haunted house.

JS: The basis for some future project?

MR: Yeah, but the paintings are objects, so I keep thinking, “How would I make them an interesting component in a film?” Right now I’m archiving all of the paintings: Photographing them, and finding as much information as I can about the publishers, dates, and authors. It’s fun and I am learning a lot about his professional work in the process.

JS: He saw some of your films, besides The Birds of Chernobyl?

MR: He saw Gowanus Haze and The Birds of Chernobyl. When I showed him Gowanus Haze, at that point I don’t think he realized that it was his voice on the soundtrack, and that made me feel really sad, because I was excited to show it to him. We were really close. He was a deep thinker. We would talk about things I couldn’t discuss with anyone else in my family – it was nice to have that experience.

JS: That’s a really poignant thought, that he hears a voice on the soundtrack and doesn’t realize it’s himself.

MR: Well, I only say that because my mom said that. I would get really excited to work with him. My mom was taking care of him, and she would sometimes ruin the moment by saying, “Meg, I don’t think he knows what’s going on.” So this was what she was saying, but I felt like she knew, because she was always with him. I don’t know why I decided to believe that. That was what was so emotional towards the end, you think about memory differently. Or you ask yourself, how is someone like him responding to a moment? Or when do we perceive that he isn’t aware of what’s happening?

Now I’ve become interested in hand-processing, learning more about that technique. How different developers can create more interesting tones. I also want to explore time differently, using the J-K optical printer. I have 530 frames of film of my grandfather and grandmother on this porch, shot the summer before he died. It’s regular 8mm, so I blew it up to 16mm. I did this calculation, “Okay, I have this many frames. How many do I need to translate this amount of footage to a 100-foot roll of 16mm film?” I’m trying to play with the time, working with those limited frames and slowing things down by re-photographing a lot of the same frames. But I don’t know about the sound. I have this footage and I’m still trying to figure out what I’ll do with it.

Published March 19, 2015

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Joel Schlemowitz is an experimental filmmaker based in Brooklyn, New York. He is also the editor of the film section for the East Village arts/poetry community newspaper Boog City. Screenings of his films have included the Ann Arbor Film Festival, New York Film Festival and Tribeca Film Festival. His work has received awards from the Chicago Underground Film Festival, Dallas Video Festival, and elsewhere. www.joelschlemowitz.com