Interview with Stephanie Barber

By Joanna Raczynska

In the Jungle / Stephanie Barber

In the Jungle / Stephanie Barber

Stephanie Barber writes, performs, makes movies, teaches, and lives in Baltimore, Maryland. Known primarily for her short films, she has more recently been making longer form works that originate from written plays (In the Jungle, 2017) and display a marked interest in exploring performativity (DAREDEVILS, 2013). The text below is from both a conversation and email correspondence we shared during the early months of 2018, when Stephanie was developing her latest play and thinking about its subsequent screen adaptation, Trial in the Woods (2018).

dogs / Stephanie Barber

dogs / Stephanie Barber

Joanna Raczynska: The earliest of your short films I remember seeing is dogs (2000), where two dog hand puppets, Spike and Pocket, debate the meaning of life. It left me wanting to read the transcript of the film to appreciate the text more fully. Not a typical response of mine to short films…

Stephanie Barber: A lot of the films are wordy! The majority are essay films or poems or what might simply be called text pieces, with the medium (film, video) as a secondary, almost ancillary concern to the ideas presented. But, yes, dogs is a dialectic. I’m amazed by the artistic, collaborative nature of conversation. It’s a language piece we construct with each other regularly. Many are just not funny. Some are tedious but then, maybe bordering on a sort of structural tedium that I find nice. I used to have telephone conversations with my grandmother and they would sort of devolve into us just listing foods we did and did not like:

“Tomatoes?”

“If they’re ripe.”

“I like them with cheese.”

“I like Swiss cheese.”

“Yes, and cheddar, you like cheddar?”

“Yes, cheddar and I like Velveeta, your grandfather liked cheddar.”

I’m not sure my patience for this kind of conversation would hold out if I didn’t love the interlocutor, though. Small talk has the potential to become profoundly distressing pretty quickly. Maybe because conversations have the potential to be something truly astounding – a comedy piece or revolutionary starter gun – the duds feel more painful. Regardless, I like the challenge of recreating conversations as text pieces. Dialog, yes, but not dialog as an addendum to the “action” of a story or plot but dialog as the story. Dialog as the art piece. Dogs, the visit and the play (2008), the hunch that caused the winning streak and fought the doldrums mightily (2010), and DAREDEVILS are each exercises in this sort of conceit. Can the conversation itself be the establishing shot, the climax, the closure: the form and the content of the piece?

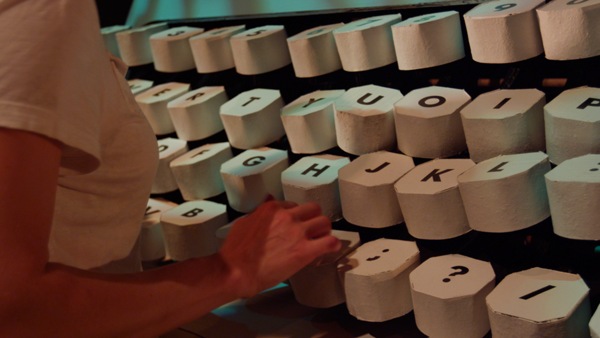

the hunch that caused the winning streak and fought the doldrums mightily / Stephanie Barber

the hunch that caused the winning streak and fought the doldrums mightily / Stephanie Barber

Raczynska: Your writing lives on many public platforms. For instance, you frequently post haikus on Facebook like this one:

the censoring hand

arouses a suspicion

worthy and delight

Barber: I like this one because of the switch of tense and use that “worthy” plays. It’s a different way of using language. I volunteer as a tutor at an adult literacy center here in Baltimore and I learn a lot from people who handle language differently than I always have. I teach a woman who speaks French and Wolof to read in English which is the weakest of her three languages, and she has no relation to written text in any language. She jerry-rigs English because she doesn’t have all the proper tools, and where we end up linguistically in conversation is so intelligent.

Raczynska: The effort involved in translating and relaying meaning is foregrounded in your films. Can you address the role of the audience in your work? A 360-degree pan within In the Jungle directly highlights the faces of the audience watching the play within the film. Why did you decide to do that?

DAREDEVILS / Stephanie Barber

DAREDEVILS / Stephanie Barber

Barber: The 360-degree pan, for me, is doing a few things. One is a release for the camera – these two circular pans are the only camera motions in the piece. All other shots are still, fixed, and passive. I’m interested, musically, in the interplay between camera stasis and motion. In DAREDEVILS a similar game is played. There is one extravagant tilting, tracking, panning, zooming shot at the end of the film after a series of still camera work. In dogs there is one motion at the end of the film, a slow zoom on Spike’s face as he reads his love poem. I like the idea that the camera needs to assert a bit of personality. Something tantrum-esque in the shaking off of its silent watcher role and reveling in a florid motion. Though, in each of these cases the motions are incredibly strict so, alas, the camera is not really partying.

Another architectural motivator for these 360-degree pans comes from the script which is divided into three acts. This is, of course, a classical structure for screenplays (five acts, Shakespeare; three acts, Hollywood). I use this structure all the time but fill it with, perhaps, less recognizable markers of “set-up, confrontation, resolution.” I like the humor in a classic and elegant structure holding a less identifiable story. So these two slow pans articulate the space between the three acts. (De La Soul and Bob Dorough all seem to know).

The role of the audience is an altogether different question and very funny phrase: “role” suggesting something entirely different than audience. I absolutely think about the audience when writing and scheming a piece of work. I think about what I can do to them. What I can poke or press, and I have epic and heartbreaking imaginings of what they will do to me in turn. This awareness of an actual and yet, not actual audience is, for me, the most profound element of art production and the most precise metaphor for existential terror.

Because I am a godless religious fanatic I have, for better or worse, placed my understanding of purpose and meaning at the feet of Art. Art, as a cultural, spiritual grappling with the ineffable nature of consciousness, is necessarily mutable and (like Wittgenstein’s notion of language as a living, changing, growing, dying game) for it to grow and change and die it must be used. Art needs an audience to use it: for solace, for target practice, or to rethink it for a new time, a new place. My students often tell me what their pieces mean, a clear and rigid branding, not an option of many. Or if another student speaks about something they had not intended they dismiss this as the “wrong” interpretation. I’m into Emile Durkheim’s notion of anomie and how it expresses a social (or individual) schism in a society with too rigid a social system OR too loose a social system. How can a piece of art both hold its space and ideas while allowing itself to be altered by all who use and change it?

Raczynska: Nestled within the play and the film In the Jungle is a short, Nature as a Metaphor for Economic, Emotional and Existential Horror (2016),that layers a running tiger animation over a slide show of idealized domestic interiors, presumably from glossy interior decorating magazines. Tell me about your use of short films within the longer form.

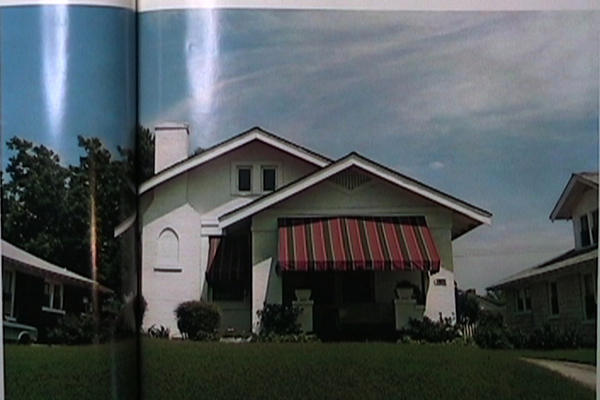

Nature as a Metaphor for Economic, Emotional and Existential Horror / Stephanie Barber

Nature as a Metaphor for Economic, Emotional and Existential Horror / Stephanie Barber

Barber: Thinking about the tiger running through the design magazine living rooms AND the songs that the DJ plays AND the song The Musician in DAREDEVILS creates – or the podcast in that same movie – AND the poem that Spike reads to Pocket in dogs AND the play that the friends go to see in The Visit and The Play (2008)… and I guess I could go on. It does seem to be a move I like to use. I don’t think I’ve ever realized this! I love how Moby Dick is a pretty simple adventure story with all of these other stories and a lot of whale information cleaved into it. Or, Claudia Rankine’s Citizen which is a shifting, wily treatise on contemporary racism and violence which moves searingly between small snippets of story from different perspectives and an internal narrator who uses the second person and scripts for “situation videos,” almost as if all the stories are circumnavigating the ideas, whipping them into a circular frenzy supported by multi-platform ruminations.

In telling stories there is the telling and there is the story. A lot of my work has been engaged in extreme distillation, like the very short sculptural 16mm films I’m making currently and the haiku I write daily and most of my earlier films and videos. In the longer pieces that I’ve been making these last five or so years there is a very different, very musical way of unfolding concepts through time that I am just beginning to be able to upset. How to simultaneously upset and delight? This use of story within story is sometimes a moment away from “the task at hand” and sometimes a summation of the larger form.

the visit and the play / Stephanie Barber

the visit and the play / Stephanie Barber

Raczynska: How does your sound work and song writing function within your films?

Barber: More content, concept, and artistic play is at large in the soundtracks of my films, and yeah, I think less work is being done by the image. This is generally an inversion of the power balance in experimental film, video art, and traditional narrative cinema. It’s not uncommon for artists from each of these traditions to pick someone else’s music to use as background for the piece, with the implicit understanding that the “piece” is the visual component. I’m not sure why I worked against this. Maybe it’s because I was raised in a very musical family or maybe because of poetry or my childish, ever-present rebel stance, but my earliest pieces worked in this way.

It’s possible I think that ears are smarter than eyes. Humans are so ocularcentric but to me this sense is a less riveting relayer of ideas. It also seems to be so co-opted. If I had any filter or pride I would not say that eyes are more entrenched in capitalism’s evil grip. I get physically irritated at work which is visually beautiful. I can’t explain it but I feel as if I am being manipulated, bought and sold for cheap. I want my beauty on the astral plane!

Raczynska: With both of your more recent 16mm sculptures – the parent trap (2017) and 3 peonies (2017) – there is a definite form (presumably the duration of a single roll of film) and a definite medium (16mm). Hole punch, light spill, beginning and end. Describe why you use the term “16mm sculptures.” How are these intended to be viewed? Are they projections on forms, single channel works? Is the term “sculpture” specific to their making, for you?

Barber: I’m thinking about them as sculptures because of the way that the material being shot –in both cases flora is being harassed in some way – is altered by an interaction with a diverging material: peonies and painter’s tape in 3 peonies,and a fern and black paint in the parent trap. In both cases the clarity suggested by the visuals is confounded by the soundtracks which introduce elements of elusive narrative. It’s interesting that sculpture has changed from an art form which was primarily engaged with thoughts about how an artist could mold material, how they could change or shape stone or wood or metal, to what I think of in contemporary sculpture as the deeply poetic gesture of bringing together disparate materials. So much effort is placed upon material. In some ways, this is simply true for all art – art is bringing together materials – but it’s the radical visibility of elements in sculpture which make this structural move so appealing to me.

the parent trap / Stephanie Barber

the parent trap / Stephanie Barber

Raczynska: The parent trap asks, “What goes when the body goes?” I’m interested in the layers of generations you have at play, the consanguinity here. We hear the voices of your grandmother, your mother, and you, is that right? The maternal genealogy, the sharing of memories, these moments of recognition seem so fleeting but so indelible.

Barber: The voices we hear in the parent trap are my mother, my sister and my grandmother as well as a nurse who took care of my grandmother. My voice is heard just for one line at the beginning. My grandmother is trying to remember a song she liked. Later, my mother and sister and the nurse are trying to remember the name of a movie (The Parent Trap, 1961.) Sometimes I try to understand what we as humans have, or own, or are. It seems like our bodies and our memories are those things which, for the most part, we have. But limbs can be lost or uncontrollable and memories too can falter and fade away. We have, in some way, our family. Our friends. But this have is so tenuous. In the collective we have our culture, our songs and movies, and this searching around for the name of the song or the name of the actress, is a beautiful thing we humans do with each other, to try to rebuild our understanding and existence through our shared remembering. We are so often telling each other what is happening. Not just what to think about what is happening, as if that were the only labile force at play, but actually what is happening is something we have decided on and constantly reinforce. The trip during which I recorded those sounds was to Florida, to say goodbye to my grandmother. I had given her a tiger muumuu some years earlier because she loved tigers – there were paintings and pillows and photographs of them torn from magazines all over her house. After she moved on to wherever she has moved on to, my mother and aunts gave me back the muumuu. [At the premiere of In the Jungle at the Parkway, in Baltimore, Stephanie wore this muumuu.]

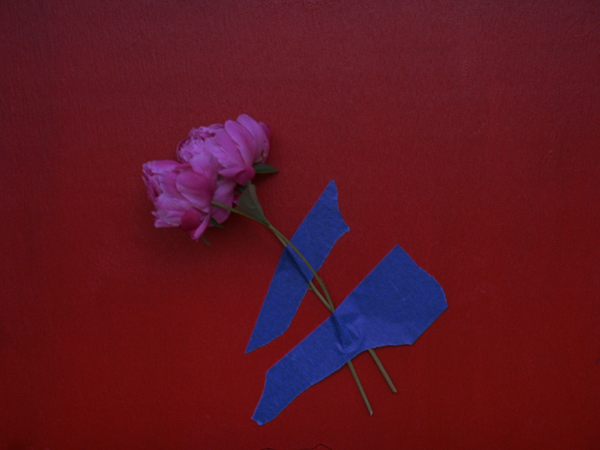

Raczynska: Can you address the decision to pour paint onto a houseplant while we hear the conversation between the women on the soundtrack? It seems to speak to your more general interest in the obfuscation of the natural, or even your question of what “the Natural” means, especially within the domestic sphere. For instance, with 3 peonies, this idea is pushed to the extreme, when cut flowers are shown taped to a red wall with blue masking tape by a woman with perfectly manicured golden nails.

3 peonies / Stephanie Barber

3 peonies / Stephanie Barber

Barber: In each of these there is the sorrow and humor inherent in the plant harassing: a none too subtle comment on the way humans use the plant world. There’s also a sort of joke on Dutch flower paintings of the 17th and 18th centuries, or really any artist’s rendering of nature, though I’m particularly moved by those. It’s true that I’m very interested in how we humans define the Natural world. It is just so childish this separation (and by “childish” I mean myopic, self-centered, uneducated, and cruel). I am also interested in how we bring the natural world into our domestic spaces through house plants and curtain patterns, fish-adorned shower curtains, pets, bird song noise machines! We love the natural world – but just some of it. We don’t want cockroaches or temperatures over 80 degrees or coyotes eating our small dogs. Just soap dishes shaped like acorns. Water in the sink, not dripping in from the roof.

Raczynska: With another recent short, the forest is offended [by suggestions of holiness and the departure of sound] (2017), you return to the use of the artificial computer-generated voice that you employed repeatedly in previous shorts such as Dwarfs the Sea (2007). Can you tell me more about your use of the automated voice in your work, across time?

Barber: The computerized voice in some of my films and videos is an attempt to sidestep the “personality” of a voice actor, and all of the implications of personhood – class, race, age, gender – that are attributed to a person’s voice, and which might confound the meaning of the words. Certainly, this is not a foolproof solution. A computerized voice itself comes with implication but it is less nuanced than human implication. I’m more interested in ideas about humanness than the specifics of a particular human experience. This is a place in which the technology of the written word is so extraordinary! The way that the pacing, accent, emphasis, etc. of the written word is translated through each reader’s inner (or outer) voice. I also just happen to like the computer voices. I like the way words are mispronounced or differently articulated, I like the strange pacing and thinness of the tone.

Raczynska: You continue to explore voices and shifting power dynamics through the personification of animals in your latest play, Trial in the Woods. How are you upending the cultural associations we have with specific animals: the lone, fierce wolf; the cute otter; the loyal elephant with a terrific memory? How does this dovetail – or does it – with pathetic fallacy?

Barber: Trial in the Woods was commissioned by director Sarah Jacqueline, and I finished writing it at the beginning of the year. It’ll premiere at the Mercury Theater, Baltimore, in June 2018. I’m beginning to translate the piece to a screenplay, as opposed to a script for the theater as I originally wrote it. The play is a crime procedural and an animal fable. An otter has murdered a wolf and is now on trial. It is primarily a play about ethics, the efficacy of punishment, and the challenge of understanding a particular happening through an array of perspectives. I was the victim of some serious violence last summer and spent a great deal of time contemplating the ethics of our (human, American) criminal justice system. Was alerting authorities the more moral path or could I exercise a sort of radical forgiveness, and which of these choices would be most helpful to my community and the person who committed the crime? When asked to write a play I was happy to work with these ideas that I had been swimming around in but wanted, very much, to avoid the specificity of particular human interactions.

Casting each character as a different animal helped me to skip the gender, race, age, class, etc. assumptions about crime in the USA but this also allowed me to consider what you’ve referenced earlier: my interest in the way humans contemplate the natural world. Several times throughout the play an animal will question the process of the trial, the validity of the set-up which had been devised by humans (the flaws inherent in regulation at all really) and the judge will admonish “the humans are not on trial here.” The animals are totally personified. Certainly, they are judges and lawyers and defendants and jurors but they try here and there to assert themselves as distinctly NOT human. As far as cultural associations, I worked hard against the animal stereotypes. The otter is not cute, the wolves are not lone, the owl is not wise, and the snake is not wily. Gender is pretty fluid throughout and will, hopefully at some points, be completely obscured; the voices are scripted to represent a variety of ages, locales, races, and classes. Trying to avoid ageist, classicist, racist implications when pairing a vernacular with an animal was a challenge, though the alternative seemed equally untenable: a cast of almost 20 different animals all with the same vernacular (mine?) seemed a cruel way to write. The piece is very sad and very funny, and, as is only natural, ends in song.

Raczynska: And naturally, the only way to end this discussion is with the last haiku of yours I read:

water is the way

the end and the beginning

pools, oceans, lakes, eyes

Thanks Stephanie.

Stephanie Barber / Photo: Stacy Szymaszek

Stephanie Barber / Photo: Stacy Szymaszek

Published September 5, 2018

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Joanna Raczynska is a writer and film programmer at the National Gallery of Art.