Slow Pulsing Rhythms:

An Interview with Nazlı Dinçel

By Clint Enns

Solitary Acts #5 / Nazlı Dinçel

Solitary Acts #5 / Nazlı Dinçel

I was recently introduced to the work of filmmaker Nazlı Dinçel through a touring program titled Note to Self: The Psychosexual Films of Nazlı Dinçel. A private screening of this program took place in an editing suite at LIFT: The Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto, a cozy location given that the room normally seats three people comfortably and there were ten of us. Prior, I had only seen Nazlı's Her Silent Seaming (2014) at the Images Festival in 2015. The LIFT screening was extremely affective given the intimate, informal environment in combination with the personal nature of her films. The work confronts difficult, sometimes taboo subject matters and often focuses on moments that are generally regarded as private. The program consisted of seven of her own films and one found film, a 70’s adult educational film designed to teach couples the importance of sexual communication titled Sharing Orgasm: Communicating Your Sexual Responses (1977). It neatly complemented many of Nazlı's films, producing a Cinema 16-like experience, where documentaries, education films, and experimental films co-existed peacefully. This interview was conducted by e-mail and edited into the following form.

* * *

Clint Enns: Naz, given the intimate nature of your work who is your intended audience? What are your ideal screening conditions?

Nazlı Dinçel: When I watch single channel work, I am mainly interested in the relationship between the recorder and the recorded. In transitional phenomena, the object must survive the destruction by the subject in order to be used. This dynamic should be justified or at least addressed in any relationship including filmmaking. Making work about something other than yourself, in some ways, is more egotistical since your audience is deprived of your complete embodiment. It is impossible to completely remove “the self” from anything one makes, and sharing the body of this “self” to the point of vulnerability is a form of deprivation for the filmmaker. It allows an audience to project themselves towards something other than the(ir) self. My failures (sexual or otherwise) have the potential to evoke sensory reaction, producing either comfort or discomfort within an audience.

Any black box with a good 16mm projector would do for an “ideal” screening. I am not against sharing work on video and I believe in making work accessible, but given the nature of the sexual content it has proven impossible to make things available publicly since websites like Vimeo or Facebook have removed them in the past. If “ideal screening conditions” was meant to be taken abstractly, this moment would be right after I process my images, in the darkroom, watching the raw material I have just created before it turns into anything else. There is nothing more satisfying or terrifying than this.

Reframe / Nazlı Dinçel

Reframe / Nazlı Dinçel

Enns: Your film Reframe (2009) is a hand-processed color film constructed from eight stereoscopic slides using an optical printer. The slides were shot by an army official in Cuba between 1948 and 1950. Can you talk more about the source material and what attracted you to it? Was it the political and historical context of the photos, given that they were taken before the Cuban Revolution, or was it the way in which many of the subjects in the photographs defiantly looked toward the camera, thereby confronting the touristic gaze?

Dinçel: I found the box of stereoscopic slides in a thrift store in Milwaukee while I was learning how to use a JK optical printer. The idea was to physically transform the stereoscopic slides into a film (a two dimensional object) while maintaining the three dimensional effect of the stereoscopic image. Since the chemical process for both the stereoscopic slides and the film I was using to rephotograph them are the same (i.e. reversal film), the film became more about the projected image, or the projector rather than the film strip. I removed the gate from the printer in order to fit 35mm slide holders into the filter gate. I shot the entire film frame-by-frame, removing the slides and putting them back in by hand. I selected the eight slides thinking that the people in them might have perished in the subsequent revolution in Cuba. The photographs were taken by a U.S. Army official traveling on an army ship. He embodied the politically privileged, and may have even been responsible for the deaths of those in the photographs despite making them “immortal” in a photograph. I wanted to subvert his gaze by using an act similar to his, where the subjects of the photographs first become displaced through my optical work and in the end return the gaze. This is why it made sense to use reversal film and to hand process, which is now the only method I make work. I shoot and hand process every image I make. I feel that this is the only way I can justify using any kind of imagery. It is all realized with my own hands.

Leafless / Nazlı Dinçel

Leafless / Nazlı Dinçel

Enns: Leafless (2011) is a hand-processed film that depicts living bodies in relation to other organic materials creating a poetic textural comparison. Despite including images of physical and sexual intimacy, the work has an entirely different tone and is less aggressive than most of your other films. This film is also firmly embedded in the lyrical tradition. Moreover, the film is about a different type of bodily failure, that is, not a sexual failure but death. Your recent series Failures (2016-ongoing) seems to be following a similar trajectory. Is this series an attempt to return to these types of existential questions?

Dinçel: I don’t think death is a failure. It might be the opposite of failure, because you cannot succeed it and it ends every bodily failure. Leafless is more about decay than death. It turned into a diary film as I was collecting imagery of the body of my ex-husband and of things found during long walks along the Milwaukee River. It was only after I sat down to edit the film that I realized that the way I was framing both subjects was extremely similar. This is also why the film is silent: the images are supposed to function as rhythms, as something to purely see.

Failures will be a feature-length film divided into 28-30 sections. I have finished four sections thus far including Forgetting, Pain, Redundancy, and Inability (which is one of the films that played as part of my tour recently, under the title Void). I am not sure how long this piece will take to finish. Failures is still a working title, I am also considering renaming the series Success or Accomplishments. I think you are right in naming these concerns as existential questions. I have achieved most things by learning how to accept failure and it is something that everyone can relate to. I want to dedicate the next few years of my life to the study of human failure, but I am not sure about the final structure of the film.

Her Silent Seaming / Nazlı Dinçel

Her Silent Seaming / Nazlı Dinçel

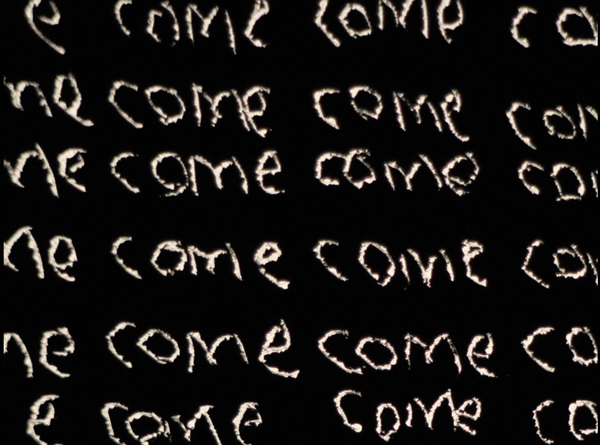

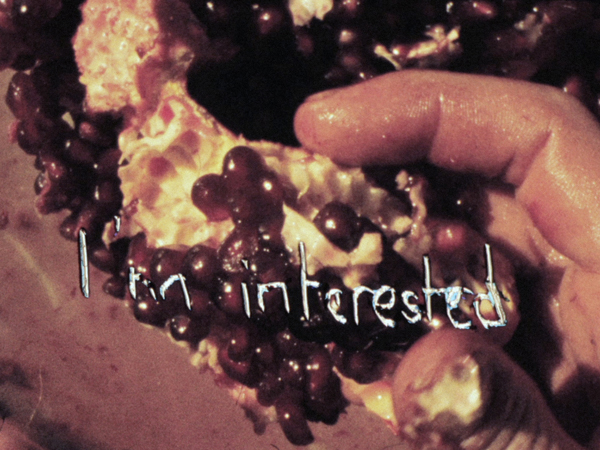

Enns: Her Silent Seaming is a handmade film involving written text between two lovers, degraded images from Leafless, the act of putting on make-up, and a pomegranate sensually being put back together. The soundtrack consists of a projector optically reading the image projected 26 frames earlier (or approximately one second earlier), a result of the optical sound mechanics on a 16mm projector. Can you talk about the significance of the title in relation to the film’s content?

Dinçel: 26 frames is the standard frame difference between the image and sound on a 16mm projector. Traditionally labs sync the sound 26 frames ahead of the image with an optical soundtrack for synchronization. Her Silent Seaming is composed of 26 frames entirely, so what you are hearing is the previous image. There is a fake "sync" throughout the whole film, which is also a failure. My sexual relationships are failing, so is my communication, and you can’t quite catch up. There is also technically no sound in the film. What produces the sound are the images themselves that are scratched as well as the cuts in the film, which also create a rhythmic quality of a metronome. I think of mathematical equations representing sexual relationships, which cannot be mathematical. But just as in Reframe, the apparatus makes these rhythmic choices, and not me.

I originally titled the film Her Silent Seeming since my voice is removed from the film. I don’t respond to the men in the text, so the film itself is supposed to function as my voice. There are over 710 splices in the film, and the text is scratched on the emulsion frame-by-frame. All 26 frame fragments were cut piece-by-piece and put up on my studio wall. They looked chaotic on the wall, but became linear when they were placed into the film. I felt like a seamstress that was making a garment (a notion further explored in Solitary Acts #5 [2015]) so I decided to change “Seeming” to “Seaming” in order to describe the labor involved.

Her Silent Seaming / Nazlı Dinçel

Her Silent Seaming / Nazlı Dinçel

Enns: The first time I watched the film, I felt the men who are quoted in it (introduced as Henry, Adam, Ben) are being insensitive. On second viewing, it seems like they are simply attempting to navigate awkward sexual encounters. I am curious about your thoughts surrounding the ethical nature of putting private conversations in the public sphere. Do you ask for consent?

Dinçel: Always. Also, I don’t feel that the men are being insensitive, I am. I was having intimate mishaps because I was sleeping with people to ease the pain of separating from my husband. Humans are often self-destructive while going through a painful process. Making this film was a form of meditation. It was an attempt to understand my own behavior and, in certain ways, it has nothing to do with the men that I’m portraying.

Solitary Acts #6 / Nazlı Dinçel

Solitary Acts #6 / Nazlı Dinçel

Enns: What about the text in Solitary Acts #6 (2015)? The text seemingly condemns your use of private conversations. You respond by having the text read out loud and played backwards. Can you talk about this gesture?

Dinçel: This all stemmed from a very sadistic/masochist friendship I had with another filmmaker. I made Her Silent Seaming with his consent, and when I was done I offered many opportunities for him to watch the film with me. He seemed indifferent to my offers and I thought that he was fearful of seeing his own behavior projected. At CUFF [Chicago Underground Film Festival] our films were programmed in the same screening and this was the first time he saw the film in public, as an audience member. He said things to me before our screening in anticipation, which he later regretted and attempted to apologize for. This is the text I used in Solitary Acts #6.

After this, he agreed to masturbate for me on film, he allowed me to use his letter, and he let me record him reading a letter I wrote to him analyzing our relationship. I was studying our actions, taking a motherly role that accepted his erratic behavior and his vapid female conquests that hurt me deeply. I was also doing research on the Oedipal complex, and realized that even if the theory has some validity, no one was considering the perspective of the mother figure. The psychoanalysis only considers the male child, and not the female that finds herself on the other side of the dynamic. I wanted to confront him (my friend and Freud) by connecting his masturbation to an imaginary child who survived an abortion I had as a teenager. His masturbation was his need to be exposed, while fearing exposure and the solitude of experiencing a sexual act with someone else. This is also connected to my solitude because I neither had him nor the child. In the film, I read his letter and he reads my words written to him, as we would read a letter in private. The text that he reads is backwards and therefore abstracted since I don’t feel that the words hold any meaning. The reversing is also gestural because my words, read by his voice, mimic the image since the image is backwards as well.

Enns: What happened to Solitary Acts #1-3? Do those parts not exist yet?

Dinçel: I want to make them after going through menopause since elderly sexuality is as taboo as childhood sexuality. I am thinking they could be masturbation films as well, but I haven’t decided yet.

Solitary Acts #4 / Nazlı Dinçel

Solitary Acts #4 / Nazlı Dinçel

Enns: One of the major strategies you employ is to address private/taboo subject matters in the public sphere. For instance, in the triptych Solitary Acts #4-6 you deal with experiences that are not often talked about, like child masturbation, abortion, and sexual intimacy. By bring these topics into the public sphere are you attempting to subvert cultural and social norms or are you intending the work to be cathartic, a gentle reminder to the audience that their traumatic or embarrassing experiences are commonplace?

Dinçel: I don’t think these acts are meant to be transgressive or to solely function as feminist gestures. I use strategies that historically subvert the male gaze but these are confrontational gestures rather than cathartic in nature. They seem to be read differently by different people and I don’t mind if I make the audience uncomfortable even though this isn’t my intent. However, I would rather make people uncomfortable than complacent. Art is supposed to make its audience self-aware, and not function as a living room couch. I want to use this as a subversive force, a force that is capable of overthrowing meaningless social structures.

Enns: Given that your work is read differently by different people, do you feel that readings of your work are gendered?

Dinçel: I hope to abolish gender.

Enns: How do you feel your work does this?

Dinçel: Gender is completely a social construction that often disables females. Generalizations made about gender differences, even if they are positive, are problematic in reaching any kind of equality between humans. Second wave feminism didn’t work. There are still inequalities between the sexes. If I (as non-white female) can have the privilege to consider myself an artist, I have an obligation to say something about it. Gender divides society based on our sex organs. If we are born intersex, we are forced into surgery as infants to fit our sex organs to be either male or female. I want to recognize this history and to destroy this construction. I want to record male bodies because I find them beautiful, just as the female bodies that men have had the privilege to represent.

Solitary Acts #6 / Nazlı Dinçel

Solitary Acts #6 / Nazlı Dinçel

Solitary Acts was born from my research into pornography theory. I wanted the framing of the female and the male to be exactly the same. I wanted to be able to show masturbation, close-up, from start to finish, focused on both sex organs unlike commercial pornography. Both hands that masturbate have gold nail polish on. I wanted them to seem like the same organ with the same pleasure. Both organs visibly reach orgasm, in reverse. I cannot make a claim to generalize readings of my work as gendered, because I don’t believe in dividing anything based on gender. I don’t want to limit myself to only a female audience, because ideally any gender should be able to relate to my work, in order to empower all females.

Enns: I am curious as to your thoughts on the term “entitled aesthetics,” coined by Toronto-based curator Amy Fung to describe work that “harkens back to a legacy of experimental artists and their works and aesthetics from the 60s and 70s?”[1] She explains:

By this term, entitled aesthetics, I am speaking to the lineage-chasing artists and curators who choose to regurgitate canonical aesthetics from decades past. Entitled aesthetics inbreeds a type of navel gazer who do [sic] not understand that aesthetics are time-sensitive tangents born of socio-historical contexts. For the genre of experimental cinema, like Abstract Expressionism in painting, or like Beat poetry in literature, the canon has been filled by a very narrow demographic that benefited from a post-war condition that turned towards abstraction in form and content as a reflection of the world, and at the base of this, of course, is a systematically racist, sexist, and ableist society. It wasn’t only white men doing these things, but only they are celebrated and remembered, and as a result, continually re-hashed to stretch their legacies further.[2]

Like Fung I am also critical of this legacy despite feeling that some canonical works have merit and that it is important to critically engage with our cultural history. I also feel that many artists have been overlooked given the oppressive nature of the canon. In contrast to Fung, I do not feel the problem is an aesthetic one nor do I feel it is fair to blame specific artists for engaging with the aesthetic tradition of their choice. I feel the problem is systemic and it is the fault of those who have power, namely, the curators, programmers, and academics. Overcoming this requires serious archival research in order to champion artists that were overlooked and it requires challenging conservative programming practices, that is, programming that simply re-enforces dominant narratives.

Do you feel your work is challenging an “entitled aesthetic” despite engaging with this legacy?

Dinçel: What Amy doesn’t realize is that this statement actually functions to empower the dominant voices (i.e. cis white males) that have been given priority through the showcasing of their work, thereby establishing an experimental film history. She claims that her argument is not medium-specific, but then directly describes the eras of the 60s and 70s where emulsion-based practices and handmade techniques were being explored as something that was “time-sensitive.” She is also forgetting to champion for those minority groups that weren’t entitled and were also engaging in these techniques, but in obscurity, further marginalizing them.

If I am to use a film camera or employ a specific film technique, am I automatically working in this vague aesthetic category Amy has imagined? Am I not making and establishing my own aesthetic choices? Is my framing simply a mirror of those white men who are still prioritized before me because I have decided to hand process my own work? I don’t understand her argument. It seems that she is simply refusing to engage with a certain type of work, the category of work hidden behind “entitled aesthetics,” which is unfortunate. I would like to know the specific classifications and lists of what constitutes an “entitled aesthetic.” How can an aesthetic choice in filmmaking be categorized as another person’s? My work should automatically subvert the white male canon simply because I am not a white male. It isn’t helpful to reject something in order to create inclusion. I do agree with her that artworks should ideally transcend medium specificity. The thought and gesture is more important than the medium that represents the thought.

Enns: Do you ever get sick of working with film?

Dinçel: My relationship with filmmaking is the healthiest relationship I’ve ever had, albeit obsessive. I don’t think it is possible for me to get tired of it in any capacity.

Elements from Failures / Nazlı Dinçel

Elements from Failures / Nazlı Dinçel

NOTES

1. Amy Fung, “Entitled Aesthetics,” POST specific POST, postspecificpost.tumblr.com/post/138866968939/entitled-aesthetics

2. Ibid.

Published September 21, 2016

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Clint Enns is a visual artist living in Toronto, Ontario. His work, which primarily deals with moving images created with broken and/or outdated technologies, has shown both nationally and internationally at festivals, alternative spaces, and microcinemas. He has a Master’s degree in mathematics from the University of Manitoba, and has recently received a Master’s degree in cinema and media from York University where he is currently pursuing a PhD. His writings and interviews have appeared in Leonardo, Millennium Film Journal, INCITE Journal of Experimental Media, and Spectacular Optical.