Three Great Phonographers:

Warhol, Nixon, and Kaufman

By Brian L. Frye

What is phonography? The word is derived from the Greek roots “phon,” which means “sound,” and “graph,” meaning “to write or draw.” So phonography literally means “sound writing.” Historically, phonography referred to Pitman shorthand, an abbreviated system of writing invented by Isaac Pitman in 1837. Stenographers use shorthand to record speech. Pitman shorthand was called phonography because it is a form of phonemic orthography: its symbols correspond to sounds, and words are written phonetically.

Today, phonography refers primarily to field recordings, or audio recordings created outside of a recording studio. Specifically, it refers to field recordings of ambient sounds, which are collaged into soundscapes. So, a phonographer is a person who records ambient sounds and uses them to create soundscapes. As one prominent phonographer explains: “Auditory events are selected, framed by duration and method of capture, and presented in a particular format and context, all of which distinguishes a recording from the original event during which it was captured.”[1]

I will use the term phonography in an amalgam of its historical and modern senses. Historically, phonography meant the use of symbolic representations of phonemes to create a record of speech. Today, phonography means the creation of audio recordings of the natural world. But if phonography means “sound writing,” it seems that it is best understood as a method of capturing how language sounds. Accordingly, I will define phonography as the creation of documentary audio recordings of speech.

Of course, given this definition, there are innumerable incidental or accidental phonographers. Every day we create countless audio recordings of people speaking. A few capture moments of great significance and are preserved, but the rest are mundane and quickly forgotten: voicemails, customer service calls, and so on. Centuries of audio recordings are created every day, only to be destroyed or to sink into an ocean of noise, which amounts to the same.

But certain intrepid phonographers defy this norm of indifference to the sound of speech. They record out of an impulse to preserve the texture of life as it is lived and experienced, in conversation with others. As a result, they produce comprehensive audio archives of remarkable historical value, by capturing the total aural experience of a specific person, at a particular moment in time. In this essay, I will consider the archival contributions of three great phonographers: Andy Warhol, Richard Nixon, and Andy Kaufman.

Warhol, Nixon, and Kaufman exemplify three modes of phonography: anthropological, historical, and psychological. Warhol documented the language and self-perception of a subculture that was ignored or pathologized by mass culture. Nixon created the most comprehensive record of a presidential administration that will ever exist. And Kaufman captured moments in which ordinary people responded to violations of social order.

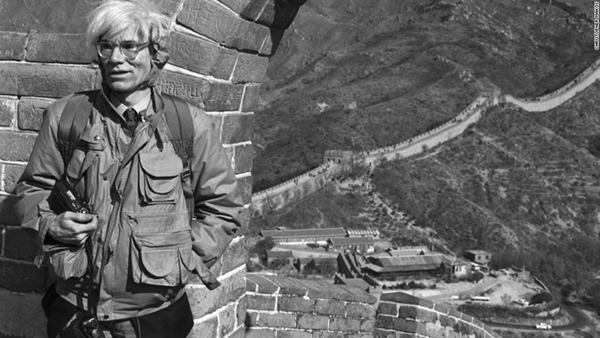

Warhol

Andy Warhol (1928-87) was an American artist, best known for his iconic paintings of commercial products and celebrities, including his Campbell’s Soup Can paintings and his Elvis and Marilyn Monroe portraits. But Warhol was a multi-media artist. He created innumerable drawings, sculptures, photographs, and works of performance art, and was a prolific filmmaker, directing about 600 films between 1963 and 1968.

Warhol religiously collected the ephemera of his daily life: correspondence, photographs, souvenirs, receipts, and so on. In 1974, he began sealing his ephemera into cardboard boxes, which he referred to as Time Capsules. When Warhol died in 1987, he had created 610 Time Capsules, which The Andy Warhol Museum is still cataloguing.

Warhol was also a dedicated phonographer. Beginning in the 1950s, he used a reel-to-reel tape recorder to record his mother Julia Warhola singing the Carpatho-Rusyn folk songs she had learned as a child. Sometime in 1964 or 1965, Warhol purchased one of the first cassette tape recorders and started recording his conversations.[2] Over the course of two years, he recorded 24 hours of conversations with his friend Ondine. Then, he hired four amateur typists to transcribe those conversations and released them as a “novel.”

I did my first tape recording in 1964. I’m trying right now to remember the exact circumstances of what I made my first tape recording of. I remember who it was of, but I can’t remember why I was carrying a tape recorder around with me that day or even why I had gone out and bought one. I think it all started because I was trying to do a book. A friend had written me a note saying that everybody we knew was writing a book, so that made me want to keep up and do one too. So I bought that tape recorder and I taped the most interesting person I knew at the time, Ondine, for a whole day. I was curious about all these new people I was meeting who could stay up for weeks at a time without ever going to sleep. I thought, “These people are so imaginative. I just want to know what they do, why they’re so imaginative and creative, talking all the time, always busy, full of energy… how come they can stay up so late and not be tired,” and pretty soon it would be four days later. I was determined to stay up all day and all night and tape Ondine, the most talkative and energetic of them all. But somewhere along the line, I got tired, so I had to finish taping the rest of the twenty-four hours on a couple of other days. So actually, A, my novel, was a fraud, since it was billed as a consecutive twenty-four hour tape-recorded “novel,” but it was actually taped on a few separate occasions. I used twenty tapes for it because I was using the small cassettes. And right at that point some kids came by the studio and asked if they could do some work, so I asked them to transcribe and type my novel, and it took them a year and a half to type up one day! That seems incredible to me now because I know that if they’d been any good they could have finished it in a week. I would glance over at them sometimes with admiration because they had me convinced that typing was one of the slowest, most painstaking jobs in the world. Now I realize that what I had were leftover typists, but I didn’t know it then. Maybe they just liked being around all the people who hung around at the studio.[3]

In November 1968, Grove Press published the transcripts as a novel. Apparently, Warhol wanted to title it Cock, but agreed to use the title a.[4]

While a purports to be a transcription of a recording of twenty-four consecutive hours of the life of Ondine, it actually consists of transcriptions of five separate recordings: a twelve-hour recording made in August 1965, three recordings made in the summer of 1966, and a recording made in May 1967. Ultimately, Warhol recorded twenty-four one-hour cassette tapes. The tapes were transcribed by four women: Maureen Tucker, the Velvet Underground’s drummer; Susan Pile, a Barnard student and Factory habitue, and two high-school students. None of them were particularly good typists, and they assumed that their transcriptions would be corrected. But Warhol liked their mistakes and decided to keep them in the book. He did change the names of most of the characters, as well as editing comments he liked or disliked. According to Billy Name, the title a was a reference to amphetamine, as well as an homage to e.e. cummings.[5]

As Scherman and Dalton observe, a shows how transcribing a conversation changes its meaning. Not only do the intentionally preserved typos and transcription errors obscure the content of the conversation, but the transcript cannot capture the texture of the voices or the soundscape in which they are embedded. While the transcript present in a is notoriously flat and opaque, the tapes are quite different. “Buried amidst Warhol’s thousands of archived recordings, they convey Warhol’s and Ondine’s mid-sixties world with a fascinating immediacy.”[6]

Warhol also recorded hundreds of hours of conversations with Brigid Berlin (aka Brigid Polk), in which they discussed her family, among other things. In 1971, he wrote Pork, a play based on those conversations. Warhol’s draft of Pork consisted of 29 acts and would have taken about 200 hours to perform. Presumably, he just had all of the tapes transcribed. Playwright Anthony Ingrassia edited the transcripts into a two-act play that opened on May 5, 1971 at La MaMa in New York and ran for two weeks, then moved to the Roundhouse Theater in London. It presented a thinly disguised account of Polk’s antics at the Factory and at home, and was described as “good dirty fun.”[7]

Warhol’s tape recording soon became an obsession, and he recorded everything, everywhere, all the time. As Vogue magazine reported:

Warhol records everything. His portable tape recorder, housed in a black briefcase, is his latest self-protection device. The microphone is pointed at anyone who approaches, turning the situation into a theatre work. He records hours of tape every day but just files the reels away and never listens to them.[8]

Warhol continued to record his conversations until he died in 1987, ultimately creating about 4,000 hours of recordings.[9] His reason for recording is unclear. Scherman and Dalton argue that he had an almost pathological “obsession with the minute particulars of his daily life,” and that recording was just one expression of that obsession.[10] While their observation is consistent with Warhol’s practice of preserving ephemera, it does not explain why he chose to record, or why he chose to record conversations.

Warhol referred to his tape recorder as his “wife,” and explained that he recorded in order to create emotional distance between himself and the world:

So in the late 50s I started an affair with my television which has continued to the present, when I play around in my bedroom with as many as four at a time. But I didn’t get married until 1964 when I got my first tape recorder. My wife. My tape recorder and I have been married for ten years now. When I say ‘we,’ I mean my tape recorder and me. A lot of people don’t understand that.

The acquisition of my tape recorder really finished whatever emotional life I might have had, but I was glad to see it go. Nothing was ever a problem again, because a problem just meant a good tape, and when a problem transforms itself into a good tape it’s not a problem any more. An interesting problem was an interesting tape. You couldn’t tell which problems were real and which problems were exaggerated for the tape. Better yet, the people telling you the problems couldn’t decide any more if they were really having the problems or if they were just performing.[11]

According to Ronald Tavel, Warhol recorded conversations because he was interested in how people sounded, rather than what they said. “For most people a voice conveys information – facts, a narrative. ‘But I don't think that’s what it represented to Andy,’ said Tavel. ‘It was sound. That’s what he was interested in.’”[12] Warhol himself claimed that he was interested in conversation because it is dynamic, rather than static:

I really don’t care that much about ‘Beauties.’ What I really like are Talkers. To me, good talkers are beautiful because good talk is what I love. The word itself shows why I like Talkers better than Beauties, why I tape more than I film. It’s not ‘talkies.’ Talkers are doing something. Beauties are being something. Which isn’t necessarily bad, it’s just that I don’t know what it is they’re being. It’s more fun to be with people who are doing things.[13]

But Warhol also suggested that he recorded his life simply in order to preserve a record of his experiences:

I have no memory. Every day is a new day because I don’t remember the day before. Every minute is like the first minute of my life. I try to remember but I can’t. That’s why I got married – to my tape recorder. That’s why I seek out people with minds like tape recorders to be with. My mind is like a tape recorder with one button – Erase.[14]

Warhol’s archives of recordings absolved him from the obligation to remember, indeed became his memory, translated into a physical form. He preserved his experiences in order to ensure that they outlived him. In a sense, he cheated death by entrusting his memory to technology. He was the original life-logger, preserving an exhaustive record of ephemeral experiences that would otherwise be lost to history.

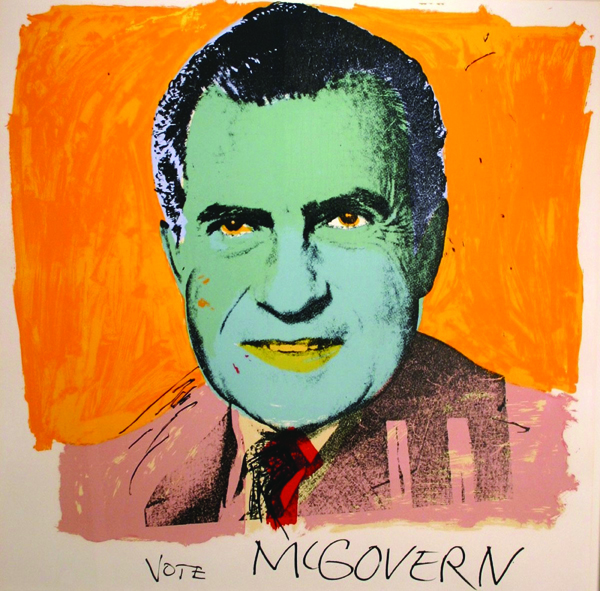

Nixon

Richard Nixon (1913-1994) was the 37th President of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A former United States Representative, Senator, and Vice-President, he was elected President in 1968, re-elected in 1972, and resigned in 1974, in order to avoid impeachment.

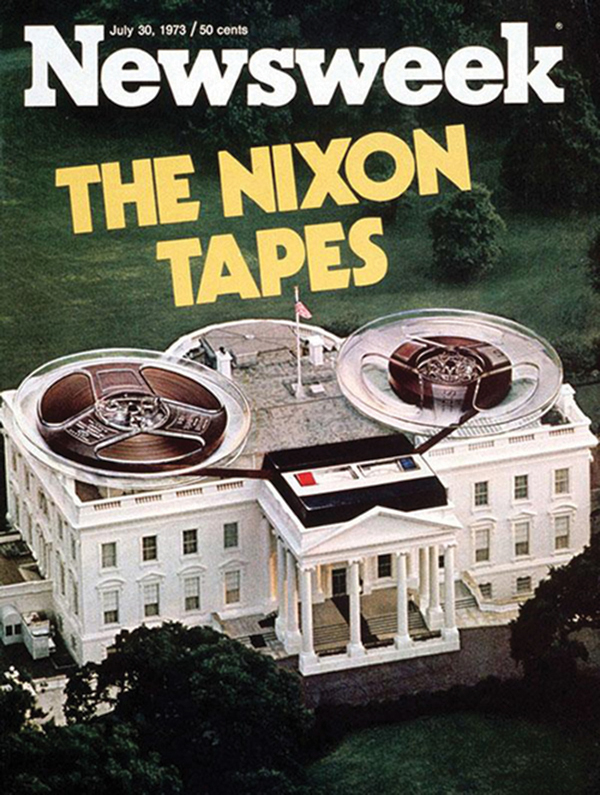

Nixon had many successes. He ended the Vietnam War, opened diplomatic relations with China, signed the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty with the Soviet Union, enforced desegregation, and created the Environmental Protection Agency. But today, Nixon is associated primarily with the Watergate scandal and subsequent investigation, which led to his resignation. Nixon’s implication in the Watergate conspiracy depended primarily on his decision to secretly record many of his conversations. Nixon ordered the installation of a secret taping system and recorded many of his conversations and telephone calls. Those recordings proved his involvement and forced him to resign. As a result, Nixon is probably the most notorious phonographer in history.

However, Nixon was hardly the first president to record his conversations and telephone calls. Presidents Roosevelt, Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson all had secret recording systems of increasing scope and sophistication. Roosevelt installed a secret recording system in 1939, at the suggestion of his stenographer, and recorded about eight hours of press conferences. Truman inherited Roosevelt’s system, which someone used to create about ten hours of largely unintelligible recordings before Truman ordered its removal in 1947.[15] Eisenhower installed a secret recording system in the Oval Office and recorded about 15 hours of meetings, including a meeting with Vice-President Nixon. Kennedy installed a secret recording system in the Oval Office and Cabinet Room and recorded about 260 hours of conversations and telephone calls. Johnson expanded Kennedy’s system and recorded about 800 hours of conversations and telephone calls.[16]

Johnson’s taping system was removed before Nixon took office in 1969. Nixon claimed that he ordered Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman to remove it.[17] But Jack Albright, Commander of the White House Communications Agency, recalled that Johnson ordered its removal after Nixon learned of its existence.[18] In any case, Johnson and Haldeman eventually convinced Nixon to install his own secret taping system.[19] In February 1971, the Secret Service installed hidden microphones in the Oval Office and the Cabinet Room, connected to tape recorders operated by Secret Service agents in the White House basement. In April 1971, the Secret Service installed additional microphones in Nixon’s office in the Executive Office Building and tapped the telephones in the Oval Office, Nixon’s EOB office, and the Lincoln Sitting Room. And in May 1972, the Secret Service installed a taping system in Nixon’s study at Camp David.[20]

Notably, the secret recording systems installed by Nixon’s predecessors all required manual activation. In other words, the President or one of his aides had to decide to create a recording of a conversation or telephone call, although they often created unintentional recordings when they forgot to turn the system off. By contrast, Nixon’s secret taping system was sound-activated and linked to the Presidential Locator System. In other words, the system turned on when Nixon entered the room and automatically recorded any noises made in Nixon’s presence. As a consequence, Nixon’s system recorded all of his conversations and telephone calls, rather than only a selection.[21]

Nixon decided to create a comprehensive record of his administration only because he reasonably believed that it was private and protected from disclosure. Ironically, Nixon’s administration is the most historically transparent presidential administration that will ever exist, precisely because he believed that everything he documented was secret. While Nixon recorded more than 2,500 hours of conversations, the relatively small number relating to the Watergate scandal have received the lion’s share of attention, not to mention the 18.5 minutes that no longer exist. Moreover, most researchers rely on transcripts of the recordings, rather than the recordings themselves, even though the overwhelming majority of the recordings are readily available on the Internet.

Like his predecessors, Nixon had two reasons for secretly taping his conversations: immediate documentation and historic preservation. For example, Roosevelt started recording his press conferences in order to ensure that reporters did not misrepresent his statements. Similarly, Johnson requested transcripts of selected conversations, in order to ensure “that his statements and wishes were accurately reported and carried out.”[22] But Johnson also relied on transcripts of the recordings when preparing his memoir. “Johnson thought that my decision to remove his taping system was a mistake; he felt his tapes were invaluable in writing his memoirs.”[23]

After the fact, Nixon insisted that the primary purpose of his secret taping system was historic preservation:

From the very beginning, I had decided that my administration would be the best chronicled in history. I wanted a record of every major meeting I held, ranging from verbatim transcripts of important national security sessions to ‘color reports’ of ceremonial events. Unfortunately, the system proved cumbersome, because it was not always convenient or appropriate to have someone in the room taking notes. In many cases, it inhibited conversation. We also found that the quality of prose varied as much as the quality of perception, and too many of the reports ended up more hagiography than history. Finally… I decided to reinstall a tape recording system.

The existence of the taping system was never meant to be made public – at least not during my presidency. I thought that afterward I could consult the tapes in preparing whatever books or memoirs I might write. Such an objective record might also be useful to the extent that any President feels vulnerable to revisionist histories – whether from within or without his administration – and particularly so when the issues are as controversial and the personalities as volatile as they were in my first term.[24]

Haldeman suggested that historic preservation was “a secondary benefit,” and that the “primary intent” of the secret taping system was to protect Nixon “from the convenient lapses of memory of his associates.”[25] According to Haldeman, the purpose of the tapes was not “to provide tapes for historians to peruse, but for the President's use alone – for reference when visitors… made statements that conflicted with their private talks with the President.”[26]

However, the design of Nixon’s secret taping system and his actual use of the tapes is consistent with a primarily historical purpose. For one thing, the decision to record all of his conversations, rather than only selected conversations, suggests a focus on documentation:

I thought that recording only selected conversations would completely undercut the purpose of having the taping system; if our tapes were going to be an objective record of my presidency, they could not have such an obviously self-serving bias. I did not want to have to calculate whom or what or when I would tape. Therefore, a system was installed that was voice-activated; talking would trigger the tape machines.[27]

Moreover, Nixon seems to have ignored the secret taping system until it was revealed in the Watergate investigation. “I never listened to a tape until June 4, 1973, when I had to do so because of the Watergate investigation. None of the tapes was transcribed until September 1973, when I was faced with the subpoenas of the Ervin Committee and the Special Prosecutor.”[28] In fact, he may have forgotten it even existed. “Initially, I was conscious of the taping, but before long I accepted it as part of the surroundings.”[29]

It was easy for Nixon to ignore his secret taping system, because his role in creating the recordings was so passive. Unlike Warhol, who carried his tape recorder and consciously chose to record his conversations, Nixon relied on the Secret Service, who effectively recorded all of Nixon’s conversations in the White House. In addition, Warhol created at least some of his recordings with the intention of using them immediately, but Nixon ordered the creation of his recordings with the intention of using them in the future.

Tellingly, Nixon’s secret White House tapes were not his first foray into phonography. As Vice-President, he recorded 112 audio diary entries, memorializing meetings, conversations, and events. “I cannot remember why I started or why I stopped making them, and they cover such a wide variety of subjects and personalities that there does not seem to have been any single purpose behind them.”[30] As President, Nixon occasionally returned to keeping an audio diary. From November 1971 until April 1973 and from June to July 1974, he recorded an audio diary entry almost every day. “These dictated diary entries do not have the orderliness of a written diary – often I would dictate on a subject one day and then expand on the same subject a day or two later.”[31]

The exhaustively comprehensive nature of Nixon’s recordings reflects his investment in his phonographic project. He documented the overwhelming majority of his conversations for three years. And he resisted destroying those recordings, even when it became clear that they could lead to his impeachment. It remains unclear why Nixon chose not to destroy the recordings. Perhaps he believed that they would be protected from disclosure by executive privilege.[32] Perhaps he believed that they were his personal property.[33] And perhaps he was committed to preserving an historical record that he and others had invested so much time and energy in creating. Nixon’s staff believed that his presidency would be epochal. Presumably he did as well.

As I have suggested in a previous article, Nixon was the home movie president, as his staff exhaustively documented his administration on Super 8 film.[34] But he was also our phonographer-in-chief, creating an audio record of his presidency of unparalleled richness and detail, which historians have only just begun to study. Remarkably, almost the entire collection of recordings is available and easily accessible.[35] While scholars have used them primarily to study the Watergate conspiracy and the policies of the Nixon administration, they also provide a uniquely comprehensive document of the transformation of the American Right in the late 60s and early 70s. Presumably, as Warhol’s recordings become available, they will provide a similarly comprehensive document of the art world and urban gay culture during a similar period of transition.

Kaufman

If people buy a record called Andy and His Grandmother, they think, ‘Oh wow, Andy Kaufman made a record with his grandmother. This must be hilarious.’ And they show a picture of me and my grandmother on the cover. And then they put it on, and it’s just a regular conversation. And people are gonna say, ‘What? What is this?’ But I like to do that to people, ya know. It would be like a big practical joke.[36]

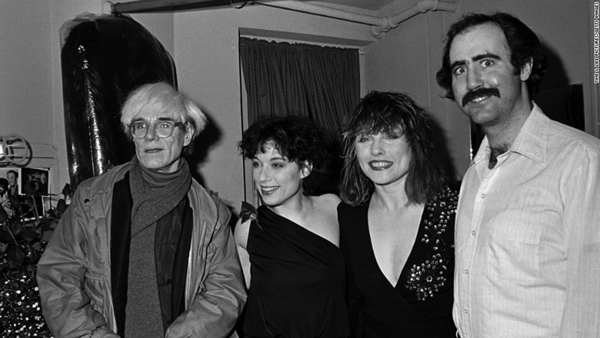

Andy Kaufman (1949-84) was an American performance artist, best known for playing the character Latka Gravas on the television sitcom Taxi. Kaufman was a provocateur. He insisted on confounding expectations, and felt no obligation to tell jokes, or even to make the audience laugh. For example, he would read The Great Gatsby in a bad British accent until the audience rebelled, or lead the audience in childish sing-a-longs. With the help of his friend and writing partner Bob Zmuda, Kaufman used his anarchic sensibility to create a unique style of performance that transformed American comedy.

Kaufman discovered phonography at a tender age. In middle school, he started a small business entertaining at children’s parties. “Sometimes, for added novelty, he brought along a big reel-to-reel tape recorder… on which he would record every kid’s voice, then play it back and make them all happily cringe.”[37] His early success was tied to his character “Foreign Man,” who spoke broken English and claimed to be from “Caspiar,” a fictional island in the Caspian Sea. As Foreign Man, Kaufman would play the theme song to the cartoon Mighty Mouse and lip sync only the line, “Here I come to save the day,” then do a series of unconvincing celebrity impressions, before doing a perfect impression of Elvis Presley. On October 11, 1975, Kaufman appeared as Foreign Man in the premiere of Saturday Night Live and was a hit. He soon became a fixture on late-night television, notorious for his unpredictable behavior.

Kaufman’s primary phonographic project began in 1977, when he bought a microcassette recorder and started recording his life. And, like Warhol, he recorded everything. Between 1977 and 1979, he recorded 82 hours of audio, from conversations with his friends and family, to arguments with his girlfriends, to provocative exchanges with strangers. For example, in one recording he talks to a group of prostitutes: “You wanna date? You wanna go dancing? You wanna have a pizza? Oh, they want money. Oh, prostitutes. I didn’t know that.”[38]

In 1978, Kaufman was cast as Latka Gravas on Taxi. Latka was based on Foreign Man. He spoke a nonsense language and routinely violated social conventions, through a combination of naiveté and perversity. Taxi was immensely popular, and Latka was a key element of its success. While Kaufman hated the sitcom format, he appreciated the opportunities provided by his new fame.

He used that fame to enable further provocation. In 1979, Kaufman incorporated professional wrestling into his act, staging televised bouts with women and proclaiming himself the “Inter-Gender Wrestling Champion of the World.” Kaufman’s wrestling character was the consummate heel, a deliberately outrageous misogynist who offered $1,000 to any woman who could pin him.[39] “He wrestled mostly female volunteers, because he couldn’t wrestle that well, and because he liked wrestling women. He’d taunt them with sexist trash talk first. He’d say women belonged in the kitchen, that they had nothing but oatmeal in their heads.”[40] Many women wrote letters to Kaufman, challenging him to wrestle, and he often agreed, if he found them attractive.[41]

Kaufman developed friendships with many professional wrestlers, including Jerry “the King” Lawler and “Classy” Freddie Blassie. In 1982, Kaufman and Blassie co-starred in My Breakfast With Blassie (1983), a parody of Louis Malle’s existential arthouse film My Dinner With Andre (1981), set in a Sambo’s Restaurant.[42] On the set, Kaufman met Lynne Margolies, who edited the film and appeared as an extra, and they soon became a couple.

It is unclear why Kaufman decided to start recording. According to Margolies, he was inspired by Steve Allen’s recordings of prank phone calls:

Andy loved comedy records like Steve Allen’s Funny Fone Calls, and he always had the idea of making a record with these recordings. He told me about it, and when he was sick he made me promise to get as much as I could out there. It was always in my head that I was always going to try, but I didn’t have the faintest idea of how I was going to do it.[43]

But Zmuda claims that Kaufman’s inspiration was Norman Wexler, a mentally ill screenwriter who would intentionally provoke and record fights for use as writing aids.[44] Zmuda briefly worked for Wexler, who he identifies only as “Mr. X,” out of fear.[45] According to Zmuda, every day Wexler purchased three tape recorders and a suitcase, which he filled with thousands of dollars in cash. Then they would travel around New York, looking for someone to provoke. For example, on one occasion Wexler crashed the birthday party of a mafia don’s mother and insulted her. On another he defecated on the floor at JFK airport.[46]

According to Zmuda, Kaufman was enthralled by Wexler and decided to emulate his methods:

Andy was mesmerized by Mr. X’s commitment to anarchy and professional sociopathy. He became so obsessed with Mr. X’s methodology and dedication to creating and then channeling mayhem that Andy persuaded me to help manufacture incidents on the street where he recorded them with his little handheld tape recorder. Later we’d listen to the results, which would provide the jumping-off point for dialing in his material.[47]

Zmuda also suggests that his stories about Wexler’s mania inspired Kaufman to create Tony Clifton, his brutally aggressive lounge-lizard alter ego.[48] Of course, Zmuda is the consummate unreliable narrator.

In any case, Kaufman at least considered using his recordings to make an album. In a conversation with Zmuda, he expressed an interest in using his recordings of his conversations with a woman who was upset about being recorded as the basis for an album: “The concept would be funny because it’s real, but it would be dramatic at the same time… Wouldn’t it be great if she killed me and you have the tapes?”[49]

On May 16, 1984, Kaufman died of kidney failure caused by lung cancer. Margolies kept his possessions, including a box of audiotapes. In 2009, she published Dear Andy Kaufman: I Hate Your Guts!, a compilation of letters written to Kaufman by women who wanted to wrestle him. As a result, she met Dan Koretzy, a co-founder of the record label Drag City, who decided to release an album based on Kaufman’s recordings. Vernon Chatman and Rodney Ascher spent three years listening to all of the tapes and editing them into a 49-minute collage album titled Andy and His Grandmother (2013).[50] According to Zmuda’s liner notes:

Andy Kaufman never stopped performing. When he stepped off-stage back into real life, his mischievous antics only intensified – and these intimate recordings that he himself made attest to that. What a treasure trove! It’s some of his best work and gives a rare insight into the maestro’s most masterful manipulations.[51]

Chatman and Ascher decided to edit the recordings into a form that resembled a traditional comedy album:

I got the sense that he wanted [the record] to be presented pretty much in the form of the popular comedy albums of the day. That was a legit format in the late ’70s – Steve Martin had massive, massive hits. It was a medium that had a cultural relevance that I think he was trying to play with.[52]

They focused on the recordings in which Kaufman was most aggressively provocative:

There weren’t directions on [the recordings themselves], but it was pretty clear during the tapes what he was most enthusiastic about. The weird thing was the parts where he was being the most unlikable – when he’s being really aggressive and pushing people to the point where they’re upset – I just thought, that is so him. It’s such a driving point of what makes him so entertaining.[53]

Many of Kaufman’s subjects asked – or insisted – that he stop recording. In fact, one track consists entirely of people asking Kaufman to stop recording. But Kaufman resists. “Why is it that nobody understands that the kind of conversations that nobody wants me to tape are the kind of conversations that should be taped?” He understood that choosing what to record is a way of invisibly falsifying the historical record. People choose not to record when they are ashamed, and thereby erase both their desires and the social forces that cause them to repress those desires.

In another track, Kaufman and a woman talk about relationships, sex, and sexually transmitted diseases, then Kaufman springs a surprise: “You know why I’m taping all this? Why? Because I’m going to be making a record for Columbia Records. You’re probably joking around now. Yeah, I am, but how would you feel if I put this on a record?”[54] Of course, he wasn’t joking. But he did want to know how she would feel if her private conversation became public. He wanted the record to document the anticipation of the shame that the record itself would cause.

Kaufman was not a comedian, because comedy was only incidental to his performances, which were intended to force people to acknowledge their discomfort with desires and experiences they do not understand. Phonography was ideal medium because it enabled him to capture the struggle to express that discomfort. In a tape he recorded a tape for his friend Elayne Boosler, Kaufman explained his theory of performance:

You’re on a railroad train, you go through a tunnel. The tunnel is dark but you’re still going forward. Just remember that. But if you’re not gonna get up onstage for one night, because you’re discouraged or something, then the train’s gonna stop. You’re still in the tunnel, but the train’s gonna stop. [So] you [have to] just keep going… It’s gonna take a lot of times going onstage before you can come out of the tunnel and things get bright again. But you keep going onstage – go forward! Every night, you go onstage.[55]

And he never did stop. He kept pushing the same buttons, as long as he was able, daring people to transcend shame by embracing it, and laughing at themselves, rather than someone else.

Conclusion

Journalists record in order to produce an article and substantiate factual assertions but phonographers record in order to produce an audio recording. For a journalist, phonography is a means to an end, but for a phonographer, it is an end in itself.

The original phonographers had to choose what to preserve and laboriously record it in shorthand. Unsurprisingly, few recordings of everyday life were preserved.[56] By contrast, modern phonographers can use audio recording equipment to easily record whatever they choose. But few choose to record their conversations, and fewer still choose to preserve them. Warhol, Nixon, and Kaufman are great phonographers because they chose to create and preserve the mundane conversations of their everyday lives. By capturing the banality of their lives, they demystified their own celebrity, and recast themselves as ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances. Like everyone else. And in so doing, they enabled us to better understand the societies in which they lived, even while remaining enigmas themselves. Because ironically, as every biographer knows, while the record of a person’s life can help us better understand the society in which that person lived, it can never enable us to fully understand that person.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Franklin Runge for research assistance and Katrina Dixon for comments.

NOTES

1. Yitzchak Dumiel (Isaac Sterling), “What is Phonography?,” at www.phonography.org/whatis.htm

2. Tony Scherman and David Dalton, Pop: The Genius of Andy Warhol (New York: HarperCollins, 2009), 259.

3. Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B & Back Again) (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975), 95.

4. Victor Bockris, Warhol: The Biography (New York: Bantam, 1989), 318-19.

5. Victor Bockris, “a: A Glossary,” in Andy Warhol, a (New York: Grove Press, 1968), 453.

6. Scherman and Dalton, Pop: The Genius of Andy Warhol, 260-61.

7. Trudy Ring, “PHOTOS: A Serving of Andy Warhol's Pork,” The Advocate (September 10, 2013), at www.advocate.com/arts-entertainment/art/2013/09/10/photos-serving-andy-warhols-pork; David Bourdon, Warhol (New York: Abrams, 1989), 312-14.

8. John Perrault, “Andy Warhol,” Vogue 155 (March 1970). See also Tony Scherman and David Dalton, Pop: The Genius of Andy Warhol, 259.

9. See www.warhol.org/collection/archives

10. Scherman and Dalton, Pop: The Genius of Andy Warhol, 259.

11. Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, 26-27.

12. Ibid., 245.

13. Ibid., 62.

14. Ibid., 199.

15. Truman’s recordings were probably created by his stenographer while testing the machine. See John Powers, “The History of Presidential Audio Recordings and the Archival Issues Surrounding Their Use,” CIDs Paper, National Archives and Records Administration, 12 July 1996.

16. See John Powers, “The History of Presidential Audio Recordings”; millercenter.org/presidentialrecordings; Alexander B. Magoun, “Did You Know? U.S. Presidents Have Secretly Recorded Conversations Since 1940,” at theinstitute.ieee.org/technology-focus/technology-history/did-you-know-us-presidents-have-secretly-recorded-conversations-since-1940

17. Richard Nixon, RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1978), 501.

18. Powers, “The History of Presidential Audio Recordings.”

19. Nixon, RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon, 501.

20. Nixon’s staffers were impressive phonographers in their own right. Haldeman kept an audio diary every day from December 2, 1970 until he resigned on April 30, 1973. H.R. Haldeman, The Haldeman Diaries: Inside the White House (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1994). Domestic Policy Adviser John Ehrlichman also recorded many of his telephone conversations.

21. Powers, “The History of Presidential Audio Recordings.”

22. Ibid.

23. Nixon, RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon, 501.

24. Ibid.

25. H. R. Haldeman, The Ends of Power (New York: New York Times Books, 1978), 192.

26. Ibid.

27. Nixon, RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon, 501-02.

28. Ibid., 502.

29. Ibid.

30. Ibid., 1091.

31. Ibid., 1092.

32. See United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683 (1974) (denying Nixon’s claim of executive privilege).

33. See 978 F.2d 1269 (D.C. Cir. 1992) (holding that the seizure of Nixon’s papers was a Fifth Amendment taking requiring compensation).

34. Brian L. Frye, “Three Great Filmmakers: Haldeman, Ehrlichman & Chapin, or Nixon’s Home Movies,” Cineaste (June 2006): 36. See also Our Nixon (2013).

35. See www.nixonlibrary.gov/virtuallibrary/tapeexcerpts; millercenter.org/presidentialrecordings/nixon

36. Andy Kaufman, Andy and his Grandmother (Drag City – DC410), LP, 2013.

37. Bill Zehme, Lost in the Funhouse: The Life and Mind of Andy Kaufman (New York: Delacorte Press, 1999), 46.

38. Kaufman, Andy and his Grandmother.

39. See www.andykaufman.com/about/bio.html

40. Alex Pappademas, “Andy, Are You Goofing on Elvis?,” Grantland (July 20, 2013), at grantland.com/features/the-lost-tapes-andy-kaufman

41. Bob Zmuda with Matthew Scott Hansen, Andy Kaufman Revealed! Best Friend Tells All (New York: Little Brown and Company, 1999).

42. My Breakfast With Blassie (1983), at www.youtube.com/watch?v=9nm-VKy4HUs

43. Nolan Gawron, “Andy Kaufman’s Lost Tapes… Found,” Esquire (August 30, 2013), available online at http://www.esquire.com/blogs/culture/kaufmans-last-tape

44. Zmuda with Hansen, Andy Kaufman Revealed!, 43. See also Erica Wexler, “The Jekyll and Hyde Life of the Man Who Wrote Saturday Night Fever,” The Telegraph, January 19, 2013, at www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/film/9787564/The-Jekyll-and-Hyde-life-of-the-man-who-wrote-Saturday-Night-Fever.html

45.. Margolies joked about hiring someone to sneak up on Zmuda, poke two fingers in his back, and say, “Norman sent me.” See Alex Pappademas, “Andy, Are You Goofing on Elvis?”

46. Zmuda with Hansen, Andy Kaufman Revealed!, 43.

47. Ibid., 53.

48. Ibid., 49.

49. Kaufman, Andy and his Grandmother.

50. Chatman is best known as a writer for the television shows Louie, South Park, and The Chris Rock Show. Ascher is best known as the director of the Stanley Kubrick conspiracy documentary Room 237 (2013).

51. Kaufman, Andy and his Grandmother.

52. Pappademas, “Andy, Are You Goofing on Elvis?”

53. Gawron, “Andy Kaufman’s Lost Tapes… Found.”

54. Kaufman, Andy and his Grandmother.

55. Zehme, Lost in the Funhouse, 144.

56. But see, e.g., Brian L. Frye, Josh Blackman and Michael McCloskey, Justice John Marshall Harlan: Lectures on Constitutional Law, 1897–98, 81 GEO. WASH. L. REV. ARGUENDO 12 (2013) (edited and annotated edition of stenographic record of Justice John Marshall Harlan’s lectures on constitutional law).

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Brian L. Frye is an Associate Professor of Law at the University of Kentucky College of Law, where he teaches classes in intellectual property and nonprofit organizations, among other things. He is also a filmmaker, who has made many short films and recently co-produced the documentary film Our Nixon (2013).