The Brutal Reality of Change *

By Dominic Angerame

|

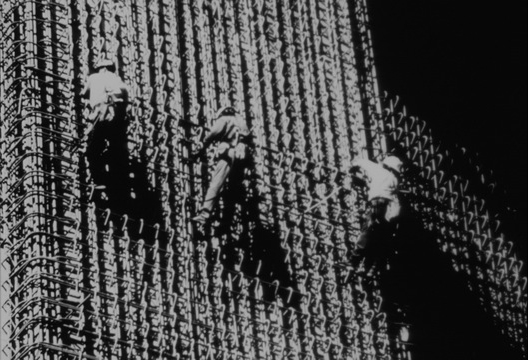

Image: Still from The Soul of Things (Dominic Angerame, 2012). Courtesy of the artist. |

Nothing is apparent to ordinary vision until

it is painted upon the window of the soul.

– William Denton (1866)

William Denton is one of the early pioneers of paranormal art and the science of psychometry. Psychometrics believes that every object emits a field of energy and that energy can transmit its entire history through touch. In the philosophy of psychometry, every brick contains the history of its creation, and if one is sensitive enough to this field of energy, historical information can be completely transferred, so that the “toucher” gains knowledge and understanding of the past. Denton performed many experiments in the field of psychometry in the mid-19th century. His research is documented in his book, The Soul of Things.

While the early psychometrics spoke literally of touch, I think of filmmaking as a kind of touch. Thus, the creation of an experimental cinema is very much akin to scientific experimentation. The filmmaker experiments with light and movement, yet his work also takes on a sense of mysticism, as he tries to find the hidden meaning of things and create a revolutionary way of capturing imagery. Such experimentation with mystery is seen in film work from Georges Méliès to Stan Brakhage.

In my filmmaking, I cannot help but be influenced by the urban area where I live, and which I love and sometimes hate. I am also influenced by the gritty urban cinematography of such 1930s filmmakers as Dziga Vertov, Walter Ruttman, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Joris Ivens. Other filmmakers I admire are Frank Stauffacher, Rudy Burckhardt, Jonas Mekas and one of my teachers, Robert Fulton, who made a series called the Street Films comprised of imagery of 1970s Chicago. Having been an urban rat most of my life in Albany, New York, Buffalo, Chicago and now San Francisco it comes quite naturally to focus my films on the urban environment.

Also, I am my father’s son: he was a union electrician and worked on construction sites almost all his life; a worker in the true sense of the word and blue collar in all respects.

When I became radicalized in the 1960s and passionately demonstrated against the Vietnam War, my father refused to get me a construction job for the summer because no one at the work site would accept my appearance. He told me to cut my hair and when I did not, he wished me luck finding a summer job.

I did find a job—making ice cubes in an ice factory. In the meantime, my father continued to work on construction sites, helping to rebuild Albany. To him, Albany was the cradle of civilization. As he saw it, everything a person could want was in that city. I was seeking further adventures, though, and began to shoot 8mm film. Shortly after that summer, I moved to Buffalo, first to Canisius College, later to SUNY Buffalo where I learned to use a 16mm camera. It was only much later that I realized that my film work had always been heavily influenced by my dad’s blue-collar background. This connection is most noticeable in the City Symphony series, which presents imagery filmed in San Francisco and portrays the urban landscape as poetic subject matter. I have filmed buildings, construction sites, the destruction of buildings, city street surfaces, manhole covers, and the Embarcadero Freeway (which was damaged by the Loma Prieta Earthquake in 1989). I finally made it onto the construction site!

City Symphony consists of Continuum (1987), Deconstruction Sight (1990), Premonition (1995), In the Course of Human Events (1997), Line of Fire (1997) and, most recently, The Soul of Things (2010). I try to capture the essence of the continually changing urban landscape, and explore the poetry of movement seen in the performance of hard manual labor by following the movements of crane operators, tar roofers, and urban construction workers.

|

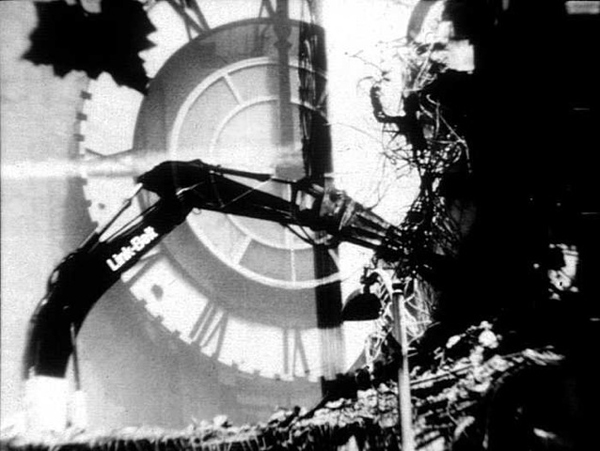

Image: Still from The Soul of Things (Dominic Angerame, 2011). Courtesy of the artist. |

The designation of these films as a series developed only after the fact; I had conceived of each piece as a separate entity, and it was only later that I realized I had created a body of work that dealt with similar themes.

I begin the process without any pre-conceived ideas about theme or direction. As such, there is no script, there are seldom any actors and there is no beginning, middle or end. I walk around the city carrying my 16mm Bolex camera and shooting images that I see as possible dynamic scenes. Sometimes, I set up a tripod in front of a construction site and shoot either the demolition or creation of a building, often exploring the surrounding urban landscape and architecture as well. The streets become my movie sets, and the construction workers, passersby, and others become my actors. I continue to collect footage until I feel that I have enough material to make a film.

Continuum began quite innocuously. I discovered a 16mm high-contrast black-and-white film which was designed for printing purposes rather than as a camera stock. Since I had had bad luck shooting in high-contrast before, I decided to do some tests. I was told that the film stock captured great blacks and powerful whites, so I decided to shoot the blackest material I could find.As it happened, workers were working on the roof across the way from Canyon Cinema,1 so I decided to film them tarring; using a mop as if they were painters working on a new canvas.

The footage that came back from the laboratory was stunning: the blacks were beautiful, and the whites were almost blinding. The light, as it reflected off of the newly mopped tar, sparkled with a brilliance I could have only imagined.

During the following months, I began to follow tar trucks. I would wake in the morning, smell tar, grab the camera and follow the smell until I reached a crew that was working on a roof. As I filmed, I began to see different reflections of tar in the sunlight and noticed the patterns and graceful rhythms of the worker’s movements as they applied the material. I noticed the shimmer of other elements as well, smoke rising from a tar truck, water spraying from sprinklers, sand blasted from a hose, and passersby stopping to look at the construction site. I found all of this quite cinematic. I began to superimpose scenes directly inside the camera, creating layers of moving images based on a spontaneous reaction to what was right in front of me.

|

Image: Still from The Soul of Things (Dominic Angerame, 2011). Courtesy of the artist. |

The next film, Deconstruction Sight starts with imagery of men using welding torches. However, as the film progresses, it does not focus in on the workers, but rather on the machines that the workers use. I had set up my camera and tripod across the street from a construction site and began to film day and night. For lights in evening, I used only the illumination of the site itself, and in one section, the kinetics of bulldozers on a moonlit night creates a science-fiction atmosphere. I was able to explore a world that most people do not see.

I have always wondered what happens to our urban spaces at night, when we are sleeping. Does some monster come out and destroy things without our knowledge? It sometimes seems so, because one can walk down a well-known city street and suddenly realize a building that once was there is no longer. Memory, though it attempts to visualize the past, rarely captures images accurately. Deconstruction Sight presents our urban surroundings as alive, even while we sleep, when machines may destroy the familiar to create something new.

This destruction, however primitive it feels, is part of the fundamental process of regeneration, which I attempted to capture in this film. In a highly technological society, we have an ideal vision of how change in our physical world is supposed to happen. Yet there is a tremendous gap between our “vision” of a better future and what is actualized. Deconstruction Sight is directed towards this gap between ideal and actual, and it opens with the following quote from Laszlo Moholy-Nagy:

Since the industrial revolution, our civilization has suffered from a growing discrepancy between ideological potentiality and actual realization.

My films are directed towards the process of change, and they investigate and expose the primitive, brutal nature of destructive forces and also find beauty in this process.

|

Image: Still from The Course of Human Events (Dominic Angerame, 1997). Courtesy of the artist.

|

My next two films, Premonition and In the Course of Human Events, deal with the Embarcadero Freeway in San Francisco. Premonition portrays the empty freeway and conveys an ominous atmosphere and a sense of impending doom. Lyrical imagery of the highway superimposed over the water in the San Francisco Bay creates a spirit of longing and remembrance.

In the Course of Human Events shows the destruction of the freeway that was torn down after it was damaged by the earthquake.This film doesn’t show people, an editing decision I made in order to convey the concept that destruction is a natural part of the evolutionary aspect of life itself. Humans do not necessarily need to perform these acts. The environment, whether natural or industrial, can and will destroy that which is no longer necessary.

Finally, Line of Fire is an addendum to these films. I had been shooting so much destruction and demolition that it came as a fitting irony when, in 1996, my apartment in San Francisco caught on fire. My girlfriend and I barely escaped the smoke and flames, and I felt as though the destructive elements I had been filming came directly into my life. This film, with its extremely black, ominous imagery, is the most personal of the series. I call it a “black comedy.” I had been filming, editing, thinking about and seeing destructive forces quite intensely when a fire forced Anna and me into the streets.

I like to allow my unconscious to direct me toward the imagery I shoot, so I often discover the reasons for certain choices only after the fact. While working on Premonition and In the Course of Human Events, I wondered about my choice of arterial freeways: Why was I drawn to the drab, gray freeway? In 1993, I found the answer: I was diagnosed with coronary arterial disease and had to have open-heart surgery. This diagnosis explained it all for me: My unconscious had been directing me inward, attempting to communicate my physical ailments to my conscious mind. In searching for this message, I had been drawn to the freeways with their systems of traffic flow, the fast and slow roadway, and their occasional blockages. The wrecking ball became an allegory for the breaking of my skeleton, which was necessary in order to restore the flow of blood, like traffic, and then rebuild a healthy city/body.

The Soul of Things, a silent, 16-minute black-and-white film was in the making for about twelve years. We see urban workers in harmony with their natural environment of palm trees, and they move with ease, as if they were actors in a narrative movie. In a science fiction vision at the end of the film an urban landscape is superimposed on a ship that sails off in the distance. Filming near the Todd Shipyards on the South waterfront of San Francisco offered me a unique opportunity to combine the industrial landscape with nature as it’s imported into the urban context. It seemed fitting to create images of the San Francisco Bay and its relationship to the architecture along the piers, where the Pac Bell Stadium (now AT&T Park) was being built, while palm trees were being planted near the Bay Bridge.

Overall, the work that I call City Symphony explores post-industrial tensions as they exist in the 21st century urban environment. I expand the possibilities of visual composition by splitting the screen into multiple images through a lens that allows me to film a circle of images within a circle of images. By doing so, I am able to reveal new and more significant meanings within the objects and the people I film and am also able to expand upon the creative language of film. Through various points of view, multiplicities and fragments, I transform urban structures into a visual array of beauty and motion.

As I film and scrutinize postmodern urban existence and the world in a state of flux, I create a narrative of selected threads of human experience, expressed as a series of related events that occur over time. The sequencing of images should work on the viewer’s sensibilities, and through them should elicit not only a narrative but also powerful emotions about contemporary society.

As I continue mining the theme of urban construction and destruction, I use what are considered to be antiquated tools—a 16mm camera, a projector, celluloid film—to create a cinema that can inspire and convey a passion towards a new vision. For me, this creation of a new visual world is the magic and potentiality of cinema. As Moholy-Nagy writes, creative visual imagery has the power to change the world in which we live. Experimental cinema is uniquely able to push back against the commoditization of art. In watching these films, we can come in contact with a truly artistic vision and reveal a new way of perceiving and reinventing the world.

|

Image: Still from The Soul of Things (Dominic Angerame, 2011). Courtesy of the artist. |

* This text was previously published in Left Curve 35 (2011). An abridged version also appears in Urban Geographers: Independent Filmmakers in the City, edited by Mark Street (New York: Berghahn Books, 2011). Reprinted by permission of the author. Edited by Rebecca Bella.

1. Canyon Cinema is a San Francisco-based, non-profit experimental film distribution company that I am the Executive Director of.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Since 1969, Dominic Angerame has made more than 35 films that have been shown and won awards in film festivals around the world. He has also been honored by two Cine Probe Series at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, and his 2004 film, Anaconda Targets, was exhibited at the Whitney Biennial. Angerame has been the Executive Director of Canyon Cinema, one of the world's renowned distributors of avant-garde and experimental film and video, for the past thirty years. He also teaches filmmaking and criticism at the San Francisco Art Institute as a visiting artist.