Interview with Bill Brown

By Sabine Gruffat

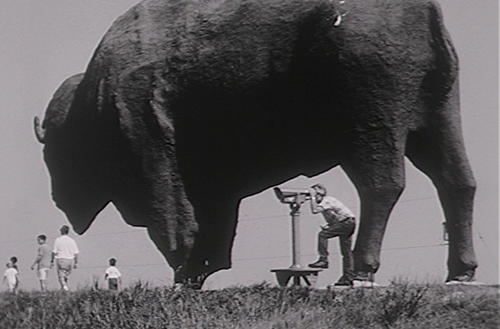

Image: Still from Buffalo Common (Bill Brown, 2001). Courtesy of the artist.

I first saw Bill Brown’s film Buffalo Common (2001) at the Onion City Film Festival in Chicago. Images from that film are still burned in my memory. After the screening I met him at a bar with a friend and he talked about how he thought the film was a failure. I was shocked that he would feel that way but I was also immediately drawn to this self-critical filmmaker. Several years later we started dating, but anyone who knows Bill knows that he has a habit of downplaying his achievements so it’s hard to get him talking about his work. This interview is my way of asking him questions I have had for a long time.

* * *

Sabine Gruffat: Although your films are mostly considered first person or experimental documentaries, you recently produced an animation called Document (2012), which owes its debt to formalist avant-garde film. Can you talk about your interpretation of Avant-Garde or Structural Film?

Bill Brown: Formally, my films have more in common with 19th century landscape paintings or 20th century street photographs than with the filmmaking avant-garde. That said, I’m a big fan of the latter, and I’m inspired by the temperament and politics of that work if not as much by the actual formal techniques (does it make sense to talk about an avant-garde as a series of formal techniques?). But now that 16mm film is vanishing, I’ve recently been thinking about it as a material thing with its own life and history, and I’ve been thinking about its importance to so many experimental filmmakers who explored its formal possibilities.

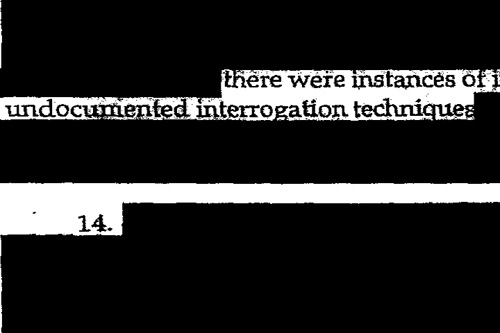

Image: Still from Document (Bill Brown, 2012). Courtesy of the artist.

In Document, I used a laser printer to transfer text from the CIA Inspector General’s report on detainee interrogation (i.e., torture) onto clear 16mm leader. The documents I appropriated are heavily redacted, so much of the information contained in them is suppressed. They are as much documents of concealment and censorship as accounts of institutionalized torture. I wanted to know what would happen if those static documents were animated. What’s interesting about 16mm film is that the area reserved for the soundtrack is also part of the visual field. So the documents I transferred onto the film make their own sounds, which are harsh and sort of violent. As if these documents are commenting on their content, or speaking up from behind the thick black lines of the redaction marks. The result is a short film that interrogates the documents with something like the brutality that the CIA report itself documents.

But I’m skirting your question, I think, about my relationship to structural/experimental film and video. When you watch a film by Tony Conrad or Hollis Frampton or Shirley Clarke, or a video by Jackie Goss, you realize that there are no rules you have to follow, or that you can make them up for yourself. You can set up a system or logic of your own and follow it. It’s like finding out you have superpowers. It’s liberating.

Image: Still from Confederation Park (Bill Brown, 1999). Courtesy of the artist.

SG: Can you talk about the character you play in your films? How do you think your performance and voiceover influence the way your films are read?

BB: Back in college, I saw Sherman's March (1986). The filmmaker, Ross McElwee puts himself on camera as this tentative, confused character: a totally unreliable narrator. He's the opposite of someone like David Attenborough, or any number of supremely confident on-screen presenters. There's a moment early in the film when McElwee appears, wearing a suit and holding a mic. He begins describing some historical moment during the Civil War. Then he falls down a hill. That's when I knew what kind of character I wanted to play in my own movies: an on-screen character who manages to sabotage his credibility. It seemed like a good way to confront the questionable authority and truth claims of documentary practice.

Putting myself in my movies also seemed like a good way to take responsibility for them. Lurking just off-screen seemed cowardly and a little creepy. Better just to step in front of the camera and out myself. I've always been more comfortable filming myself than filming other people. It's a big responsibility, putting people in your movies. Most of the time, your “subjects” have no idea what they're getting themselves into.

Image: Still from Mountain State (Bill Brown, 2003). Courtesy of the artist.

SG: Has that character changed over time?

BB: He's gotten quieter. Or disappeared behind subtitles and intertext. He seems to have less to say, or maybe after a half-dozen talkies, he's all talked out. Lately, that character has been hiding out behind the camera. You know he's there because he shoots out of focus, or struggles with his framing.

I guess I don't have as much confidence in my on-screen character as I used to. You have to have a fair amount of gumption to put your voice on the voice-over track, and stick your face in your movies. Or maybe it’s because of YouTube. Nowadays, everyone is sitting in front of a camera, confessing their most intimate secrets to strangers. It’s like being at a dinner party where everyone is talking over each other. Maybe I’m just doing what I always do in those situations: shut up and stare at the plate.

SG: Can you talk about the films that have influenced you the most? How have those films shaped your work?

BB: I mentioned Ross McElwee, especially his early road trip movies. The whole idea of making a movie while traveling–making a road trip part of my art making–came from watching those amazing Wim Wenders road movies from the 1970s: Alice in the Cities (1974), Kings of the Road (1976). Then there's Chris Marker. Sans Soleil (1983) is probably my favorite movie ever. It's a documentary made by a melancholy time traveler, s omeone who is lost in time and space, who spends his time writing letters that he doesn't expect to get a reply to. My first movie, Roswell (1994), is an attempt to rip off Sans Soleil. I should also mention Jem Cohen's movies. I was reading zines before I started making movies, and Jem's movies reminded me of the best kind of zines; a kind of dark, punk rock cinema of the cities. I discovered Walter Benjamin by way of Jem Cohen.

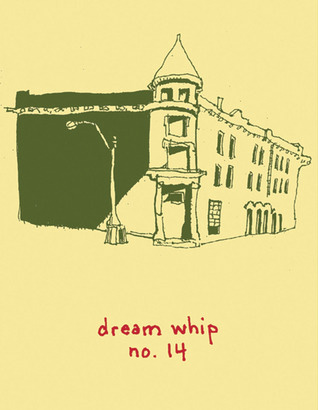

Image: Cover of Dream Whip no. 14 (Bill Brown, 2009).

Courtesy of the artist.

SG: You read a lot of nonfiction and travel writing. Is it those books that inspire your movies?

BB: No one has ever asked me that! Like I said, I've been reading zines for a couple decades now, especially zines about traveling– hitchhiking and stowing away. Cometbus. Scam. Doris. I also write my own zine, called Dream Whip. The voice-over in my movies sometimes comes straight out of it. I think my movies are really just issues of my zine. The voice, and sense of restlessness and roaming are the same. I always keep a notebook while making my movies, and some of that text makes its way into the movies, and the rest turns into a zine. When I began making movies, I was also reading more fiction that I do now–Pynchon, DeLillo, Philip Dick. These guys wrote about places that were full of secrets. Haunted worlds. My interest in memorial markers and historical sites probably comes from reading a bunch of Faulkner's novels. Of course, all these guys are interested in characters, but I always found myself more interested in the places where the characters live. So I was also reading Lewis Mumford, Jane Jacobs, Mike Davis, John Stilgoe– books about cities and geography.

SG: Your films often reference folklore and hearsay. How do these stories fit into your understanding of landscape?

BB: This is the reason there is text in my movies, the reason I can't make a movie with images alone. It's because of all this other stuff that floats around, invisible to movie cameras. Campfire stories; the things you say in your sleep; the things that people confess to you on late night bus rides; f airy tales and bathroom graffiti; t ruth and lies. All that stuff is what makes the places I film interesting to me, a sort of shimmery cloud that hovers over those places. I also like how folklore is inconclusive. It's not science or academic history. Folklore gives you access to the Rumor, which isn't always more interesting than the Truth, but it's usually more mysterious. More goosebumpy.

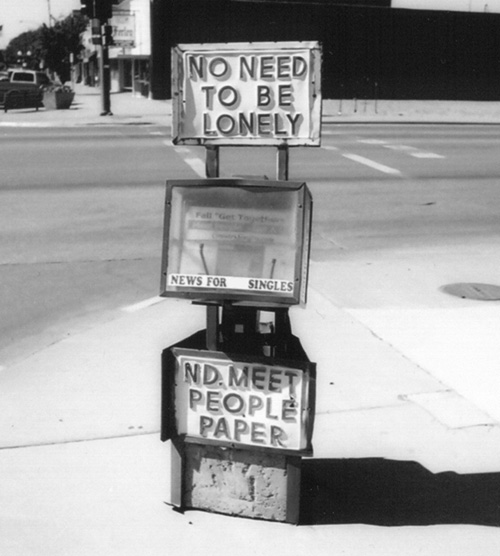

Image: Still from Buffalo Common (Bill Brown, 2001). Courtesy of the artist.

SG: I love the roadside attractions in your films. In all your films you also photograph m emorials. What is it about these types of spaces that is meaningful to you?

BB: At some point I realized that memorials do to landscapes what I'm trying to do in my movies: they stand there between you and the world beyond, using language to try to make sense out of things: to define the view; to direct your eye; or better still, to refer to what's not there. The ghosts. The invisible histories. It's a clumsy intervention sometimes. The markers have typos. Sometimes the language is outdated, or the facts are wrong. I feel a kinship and certain sympathy to these markers.

The roadside attractions are something else. I like how idiosyncratic they are. Mammoth beer bottles, giant fiberglass buffalos, and scale model Twin Towers. They point to the artistic impulses brewing inside everyone. They also exist, usually, outside commerce. They're not for sale. They're funky and eccentric and heart felt. The best roadside attractions show up in wide-open spaces, or along busy highways. At the moment when you're feeling most alienated and alone, you see one of these things, and you feel a human connection to these places that maybe you didn't feel before.

SG: You and Tom Comerford were pioneers of film touring as a way to reach new audiences. How did you get the idea for the Lo Fi Landscapes tour (2002/2005)? I like the idea of promotion and distribution as being an integral part of the work.

BB: Tom and I did a couple monster movie tours in the early-2000s. These tours were partly inspired by our grumpiness about spending lots of money on film festival entry fees only to get rejected by the festivals. But we also thought of touring as an expression of our politics. Tom and I both began making art in the 1990s, when DIY was a proud declaration of independence and autonomy (and before it was a marketing scheme for home improvement stores). It wasn't enough to be an autonomous art maker. The idea was to extend that autonomy to the entire life of the art, to its exhibition and distribution. Roll your eyes if you must, but we wanted to make art, not commodities. It turns out that an experimental film is the perfect anti-commodity. No one will buy that shit! It is pure in a way that warms the heart of an old 1990 s punk, and sleeping on floors and screening in basements and back yards was icing on the cake.

Image: Still from Memorial Land (Bill Brown, 2012). Courtesy of the artist.

SG: What is your new film, Memorial Land (2012) about?

BB: I've finally finished a short movie about a handful of people who built their own 9/11 memorials. I love the forms these homemade monuments take, and I was curious about the reasons they got built. A lot of it has to do with memory, though commerce and politics is in there, too, as well as a certain amount of egomania. The people I talked to for the film would kill me for saying so, but these monuments are way more about the monument makers than about the event the monument purports to memorialize. I think this is really poignant, and kind of funny.

SG: Where are you excited to go next?

BB: I've been dreaming of China, because that's where all the action is these days. It seems like an amazing, brutal, beautiful place. Plus I hear there are some really good roadside attractions, including the World's Largest Teapot.

Published May 31, 2012

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Sabine Gruffat is a digital media artist and filmmaker. When she isn't traveling she spends her time in Chapel Hill, North Caroline with Bill Brown.

INCITE Journal of Experimental Media

Back and Forth