Interview with Jennifer Bolande

By J. Louise Makary

Image: Movie Chair (Jennifer Bolande, 1984). Courtesy of the artist.

Though predominantly active in photography and sculpture, the multimedia artist Jennifer Bolande has generated a substantial body of work that engages with the “objecthood” and cultural experience of cinema. Both funny and elegiac, Bolande’s art explores how movies make us feel, and how the form and the phenomena of film work on us in ways that are altogether separate from film’s narrative content. Bolande uses complex strategies of remediation and signification to comment on our changing relationship to popular media and its attendant technologies, many of which are on the verge of disappearance.

I met Bolande in Philadelphia at the opening of her retrospective at the Institute of Contemporary Art (January 11 – March 11, 2012). The recurring tropes and the objects of her fascination – from stage curtains and marquees to projection screens and film stills – made me curious about the influence of cinema on her work. She met with me in her Los Angeles studio, where she was careful to point out that, for her, Hollywood feels as far away as New York.

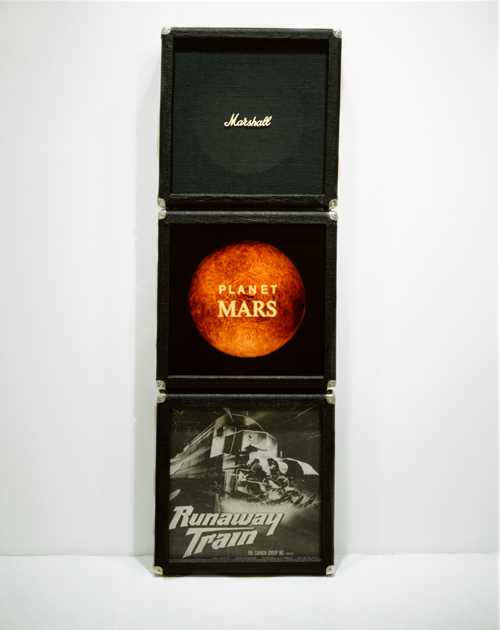

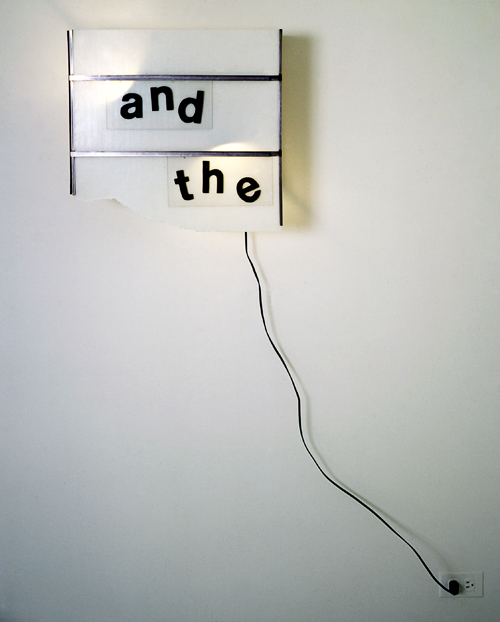

Image: Marshall Stack (Jennifer Bolande, 1987). Photo credit: Eeva Inkeri.

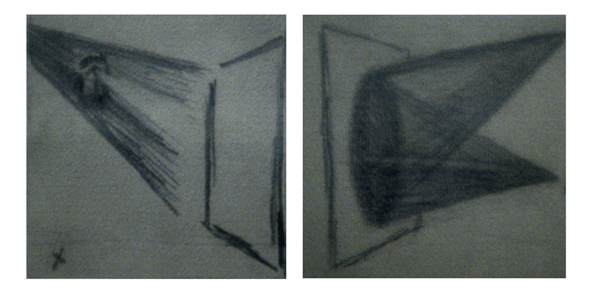

Jennifer Bolande: I saw a short documentary made by NASA called Planet Mars (c. 1979), at an exhibition on space photography. During the screening I took photos of the film from my seat. I’ve done that with a number of works. Whether it’s the end titles or opening credits, the main point of interest for me is often something peripheral to the body of the film. In this case, one of the things that appealed to me was how the beam of the projector focused on a circle (Mars), which filled the screen, forming a big, beautiful cone of orange light. I was very aware of my position in relationship to that cone, which my perceptual cone was intersecting with. The drawing Vision Cones Diagram illustrates this cinematic experience.

Image: Vision Cones Diagram (Jennifer Bolande, 1985). Courtesy of the artist.

Image: Vision Cones Diagram (Jennifer Bolande, 1985). Courtesy of the artist.

A cone is like a beam of attention. Often what is in the focal zone is not as interesting as what’s going on at the edges – I am very attuned to the periphery. I am wary of goal-orientation – the ever-pointier cone that starts out broadly and gets smaller and more focused. I go in the opposite direction. I start at the periphery and see what I can bring into it. It’s like the cone of a tornado, pulling more and more into its orbit.

Side Show (1991) was the first staged photograph I made. Prior to that I had mostly worked with found images. The scene, a kind of micro-spectacle, alludes to something happening off-screen, which seems like a cinematic idea. You can almost hear the sounds of the circus at a distance.

Side Show is from a body of work that was oriented around a circus-y theme. Another is One Day (1991),which features a Fotomat, a one-day photo processing drop-off location. This was before one-hour photos; one-day was the fastest processing you could get. It’s hard to see, but there are arrows to drop your film off on one side of the Fotomat and arrows to go to the other side to pick it up. I was standing on the top of a hill and looking down on the Fotomat, which is very similar to the point of view of Side Show. You can see directional arrows on the pavement, and all of the little photographs inside. Like, if you were coming from another planet and wanted to know what humans thought was beautiful or worthy of documentation, it was all there in a condensed form, any day. I wanted to have that sense that you are coming from afar, looking down on it, a slight aerial view. Like a lot of my work, these pieces hover around things that are on the periphery of attention or on the brink of extinction.

Image:Side Show (Jennifer Bolande, 1991). Courtesy of the artist.

J. Louise Makary: I found Side Show to be oddly moving. Because you’re using some cinematic devices – lighting, staging, off-screen space – which produce a sense of heightened emotion. You’re almost making a character out of that little stake.

Your titles often add another layer to the work: “sideshow” is a circus term, but it also seems to refer to a little figure to the side that is holding the apparatus up.

JB: The stake is a small but crucial element supporting the entire tent — so this little “sideshow” is of central importance. It’s not just an alternate center though. The stake was hammered right at the place where the two cones of light intersect. I am really interested in where things meet, in seeing or articulating the precise point where one thing intersects with or turns into, another.

JLM: There’s potential for something to happen, for you or the viewer to do something. It’s a pregnant moment, but not a decisive moment — it’s been staged, like in a narrative film.

JB: There’s a kind of framing of gestures and movements in my work, which may have something to do with my roots in dance. My works are like frozen movies.

JLM: So much of your work deals with technologies or objects that are facing extinction, or that are in transition: the Fotomat, for instance, or certain filmic or photographic processes. I read that you spend a lot of time with these objects and technologies. What is important to you about them?

JB: I spend a lot of time with everything. I’m not always sure why I am attracted to things, but since I’m working from particular to general, I honor my attractions. But, I don’t trust them entirely, so I have to wait for the newness to wear off. Sometimes you’re attracted to something because of the zeitgeist, or its superficial allure. I have a pretty elaborate filing system. I revisit things in my archive; I study things over time. Certain images or objects that are in my collections stay in there for years before I figure out how I want to engage with them. Sometimes the fact that their meaning is changing in the course of the time that I’m looking at them is part of what precipitates my having to deal with them. Something really is about to turn, and you suddenly understand what it is before it disappears.

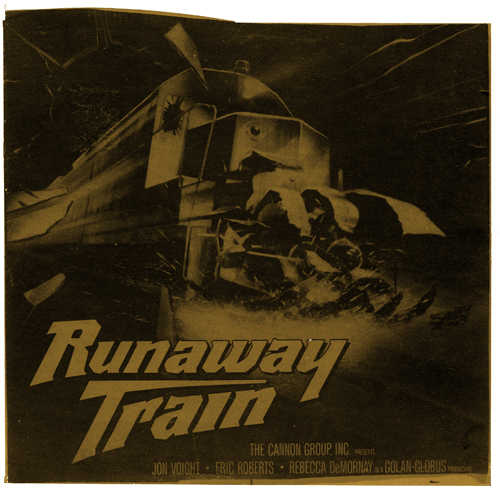

Image: Runaway Train... (Jennifer Bolande, 1988). Courtesy of the artist.

I wouldn’t say I prescriptively go out looking for aging technologies, or certain cultural artifacts on the brink of extinction. It’s more of an intuitive process. But when you look at my work over time, it’s uncanny how many times it’s come up. The movie Runaway Train (1985) figures in a number of works. I could feel that it was a metaphor. The train was a symbol of industrial progress – but what does it mean now? We weren’t quite in the information age in the mid-80s, but we certainly weren’t in the industrial age anymore. It was as if the train was going off the rails in another way – it had become separated from its cultural moorings.

JLM: Within the last 10 or 15 years that symbol of the train has lost its legibility – what it meant as a sign.

JB: It lost its currency; I think it’s still legible through a reading of history or a historical period, but it was right on the cusp then. Trains have a particular relationship to cinema and also to perspective. I thought about them in relation to perspective – barreling along a perspectival cone from the past to the present. In the mid-80s, you still had to “catch” a movie – it was before VCRs were common. The advertisement said: “Runaway Train. Coming soon. Catch it at a theater near you!” I followed its trajectory, which is a bit of a pun, but that’s what happened. First I cut out the ad from the New York Times. Then, I photographed the title on the marquee. The last part was going to see the movie. The train moves forward relentlessly, parallel to the narrative trajectory of the movie. You catch the train (and the movie) and ride it all the way through.

JLM: Your “travel” with the idea or the topic does approximate one typical, film-viewing path: you see an advertisement, you’re introduced to a film, you see it up on a marquee – that whole act of being drawn to see the film, it being sold to you and you buying into everything from the spectacle of the marquee to the experience of watching it. So it’s fitting that you say that watching the film was the last thing. I find that a lot of your work deals in that margin, using the objects associated with an experience to talk about the experience – the intuition or perception about an experience. You’re moving away from the physical object to talk about how that object is experienced culturally, such as with your photograph Movie Mountain (2004).

Image: Movie Mountain (Jennifer Bolande, 2004). Courtesy of the artist.

JB: Movie Mountain is a kind of emblem – a distillation and combination of other works or elements in my vocabulary. I have done a number of works like this. They are like a cast of characters or a family portrait. Movie Mountain is a photograph of the multifaceted photo-sculpture Mountain (2004), positioned to cast a shadow onto a movie screen. I like recombining elements or actual works into new composites, in the process adding more layers of representation, complicating their meanings.

JLM: What interested me about Movie Mountain was the final presentation, like you said, the layers of representation and how they bring attention to the viewing process. It’s fascinating to look at. This particular sculpture casts a completely idiosyncratic shadow that is itself very photographic, very cinematic. The shadow is not exactly an index, but it’s a representation cast onto the screen and you’re framing the composition in a very selective way. But you also have a second shadow of the screen itself.

JB: Yes, I love that part. There are quite a few layers to pass through, and no apparent hierarchy of importance.

JLM: The shadow calls attention to the screen. It’s no longer something that just disappears when and because something is being projected onto it. So you become more aware that the image is mediated, that you are a viewer.

JB: I have used portable home movie screens in a number of works over the years. I always have a pile of them in my studio. The corners of the screen are often rounded, which mirrors the old format of a slide or film frame that is projected upon it. I’m not sure why the screen needs to have that format, too – why did they do that?

JLM: There’s emotional content in those details. They are part of the seduction of the projection experience. They work on us on a deeper level.

JB: It’s interesting to look at why that is. Our interfaces with things are always changing. Because of the particularities of those interfaces, our engagement changes. I’m interested in engaging with things in ways that make sense but aren’t necessarily how you’d normally engage with them. Asking, how do we relate to this object, this technology? How might we relate to it?

JLM: The light in the photograph is great – is it only one source?

JB: It’s the sun! I built this at my house in the desert. It was very early in the morning, and I just opened the garage door in the studio to light the photograph. For me, sculpture is really interesting in its relationship to photography. I haven’t made many completely in-the-round sculptures; much of my work is wall-oriented and low-relief. The nature of sculpture is that you have multiple viewpoints. With photography, you’re choosing a specific perspective on an object or a set of objects, or a place, or a person. When I make a sculpture I’m continually moving around it, looking at it from different angles and distances. In this photo-sculpture (Mountain) I wanted each photograph to be legible perspectivally. Each photograph in the sculpture is of a different globe, sitting in a window. So if I was looking up at a window when I photographed it, the viewer would be looking up that window in the sculpture. It followed that premise, and the piece determined its own shape. It’s an example of going from particular to general, and not knowing what the outcome will be. I didn’t make it make that shape. It made that shape. Even though it wasn’t planned, from certain angles, its shape resembles the Matterhorn. In the photograph Movie Mountain, I oriented it to accentuate that shape. The shadow of the mountain also conjures up the Paramount logo.

JLM: Right, I can see that!

JB: I like the beginnings of movies. I get excited about the sudden field of color, the film company logos. To me, there’s a relationship between mountains and movies – the spectacle and majesty of nature that’s called up.

In New York, I went to Times Square a lot to see movies. Being in the city, embedded in the urban, I just wanted to see a jungle, or some trees, a mountain. I remember going to Aguirre: The Wrath of God (1972). The beginning of that film, with the trek down the mountain, is so amazing. I would also go see dumb movies like Greystoke [The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes] (1984), because I knew there would be a jungle in it. I loved that contrast, going to Times Square for a nature experience. I knew it was artificial but it was still good enough. So there’s that going on in a lot of my work – the nature/artifice contrast.

JLM: There are two kinds of movie experiences that you seem drawn to in your work. One is the institutional or industry-oriented experience of going to the theater, sitting in the seat, the other being the more intimate home-movie or classroom viewing experience.

JB: It’s all kind-of magic, isn’t it? Either kind provides a threshold into a different world. Being in a dark room with other people, the projection light, the sound – imagination across a darkened space.

I used to go to the ballet when I was in high school. I’d be excited for the first 10 minutes – the curtain going up, the lights, the stage set. But inevitably, once the story got onto its trajectory, I would get bored. The expectation and heightened awareness excited me more than the thing itself. This reminds me of Jack Goldstein’s films and records, which made me more aware of that moment of expectation – the reduction of an experience to an image or a sound or a single gesture. It was as if he reduced these forms to their most basic elements and made you see things in a new way. You’d put the record on – I remember a green record, Three Felled Trees (1976). You’d hear “chop chop chop – crash,” “chop chop chop – crash,” “chop chop chop…” and you’d have to flip the record over to hear the last tree fall. His film MGM (1975) holds open for extended examination something familiar that usually flickers by unnoticed: the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer lion turning its head, roaring, and blinking. This gesture is simply repeated for two minutes, long enough to change your relationship to that logo forever.

JLM: Something you said earlier, about how fascinated you were and continue to be with this sense of expectation that films provide – it’s interesting to me that this is a focus of your work because it is so important to the film-going experience. But it’s not studied as much as the content of films and what they mean on a textual level. Your work seems to deal more with film spectatorship, how these peripheral aspects of cinema affect the viewer emotionally, the excitement of being at a threshold, and how excellent movies are at making that happen, although that may be changing. Fewer people are going to see films in the theater. And it’s changing not so much people’s engagement with movie content, but how audiences experience films in terms of those threshold moments.

JB: There seem to be fewer and fewer spaces where people congregate to share an experience. 3D seems to be a last-ditch effort to get people to the movies for an experience they can’t have at home.

It’s similar in the art world. Viewership has fallen for regular gallery exhibitions. Art fairs have become increasingly dominant, which is upsetting to me, because I make exhibitions. We’re tempted to look at jpegs of art and believe we’ve really seen it. I experienced this myself while working on the exhibition catalog, which required looking at my work as jpegs for some time. I was almost convinced it was better! You can move them around without the encumbrance of material objects. To then go back to installing the work at the ICA and to re-experience all the material aspects of the work was so different, so much richer. I fell in love with certain pieces all over again. How you encounter a work, whether you have to look down at it or up at it, the textures, proximities and conjunctions of materials, there may even be electromagnetic charges to things that you sense – all of that contributes to the way you experience or understand the work. This is obvious, of course, but also easy to overlook in favor of expediency.

Another thing about the theater experience relates to what I mentioned earlier about going to the movies for a nature experience. In a true nature experience, you are made aware of your relatively small place in the universe. You are not in control. There’s a giving up of control when you become a spectator – as a film viewer, you leave your body behind to a certain degree and you go for a ride. Before the narrative ride begins, there’s such a sense of potential. I call it the “held-open space,” and that’s not only with respect to film or movies – it’s in other experiences we have in life, when we don’t know what’s important, when we just have a heightened perception of what could be. With movies, I notice this particularly during title sequences. They start to drop clues about mood, place, and characters. As a viewer I’m alert, scanning the whole screen: Where am I, what do I notice, is this going to be important later? If we could only live in that space of heightened awareness and curiosity all of the time. Good art can bring you there.

One of the other really great, influential experiences for me was Richard Foreman’s Ontological Hysterical Theater. I love, love, love this work. Foreman barrages you with a thousand fragmentary things unhinged from traditional narrative. When you come out, you can’t describe what just happened. I remember feeling really awake and alive and engaged. Foreman has talked about these “unbalancing acts,” and employs all kinds of strategies to keep himself and the viewer from going to sleep. I believe that’s what happens with traditional narrative – you can come up with a name for it, summarize it, and you think you know what it’s about, but you’re really asleep.

JLM: There’s so much emphasis on narrative logic in theatre and film. Instead, what Foreman’s work is doing, what your work is doing, is disrupting that logic. What you’re saying is that there is complete, utter enjoyment in having to be active, in being destabilized. It’s more about that experience than “the answer is X.”

JB: Exactly. It’s such a reductive way of engaging with things, to just name them. Things can get really disembodied, reduced, stripped of all nutrients, so to speak. But, you know, this is what experimental filmmakers have been engaged in – creating experiences that interrupt our complacency as spectators. I had a somewhat spotty exposure to experimental film. There were a lot of films that I didn’t manage to catch at Anthology Film Archives in the late-70s and 80s. [Laughs.] Through the increased access to that work that DVDs have made possible, I’ve been able to fill in the blanks in recent years. Also, now that I am teaching I have the opportunity to rent a lot of films for my classes. I have discovered what feel like missing links that have directly affected me. Over the past 10 years, exploring the work of Michael Snow has been a revelation, like discovering a new continent.

I just read a great book by the film critic Scott MacDonald, Adventures of Perception (2009), which is a term he uses to describe the experimental films that have forced him to expand his own perception and sense of what cinema might be. That’s what I want from cinema, and what I want from art, too.

JLM: I’m glad you brought up Michael Snow because I was thinking a lot about his art in relationship to yours. When were you first introduced to his work?

JB: I first encountered him while studying at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design because he visited while I was there. His book Cover to Cover (1975) was published at NSCAD the year I arrived. I adore this book – it’s a sequence of photographs, a movie, a sculpture, it’s a complete thing that must be experienced firsthand. Although it issues from a set of logical premises, it’s utterly unpredictable. Every time I look at it, I think I understand the structure, but somewhere along the way I lose what it is and find myself wondering, what’s going on? Now I have to turn the book over? Where am I? I show Wavelength (1967) every year in class. I must have seen it in college, but I only remembered the image of the waves at the end. Seeing it again has been so satisfying. There’s a developing awareness of a shape – a cone – that emerges through the experience of the film. It’s sensual and conceptual, dimensional, temporal, auditory, and visual.

JLM: The idea in Wavelength is of time being connected to space, not narrative. And, like you’re saying, becoming aware of this tunnel of perspective, the cone.

JB: All of its mediating layers – the gels, the different film stocks – enhance the sense of a cone that’s being intersected by planes. I’m interested in the mediating layers between the cornea of the eye and what we see and also what is behind what we see. Then beyond that plane, things that might be in the imaginary space, or that are culturally influencing how we address something or see something. I feel that’s going on so palpably in Wavelength.

JLM: You and Snow have a shared interest in framing – how things are presented to the viewer, and the prescribed conventions of how we interact with and perceive things. I see a lot of shared ground, despite the fact that your work is so radically different.

JB: Snow talks about making seeing palpable. This is something I can really relate to. He does this in his works in all media. Each medium is inflected by another – for instance, he makes what he calls “camera-influenced sculptures,” a designation I really like. A lot of his works deal with the failures or limits of media. What I really love about his work is that the viewer is simultaneously in the work – rooted in the present moment over and over – and hovering outside of it. We are continually made aware of the mediating role of the medium, which prevents us from completely identifying with what we are looking at, but implicating us at the same time. La Région Centrale (1971) does this exquisitely – it’s one of the most moving films I have ever seen.

JLM: Were you making work that dealt with theatrical or cinematic experience before you moved to Los Angeles?

JB: Oh, yeah.

JLM: Did the way you were working with it change after you moved to Hollywood?

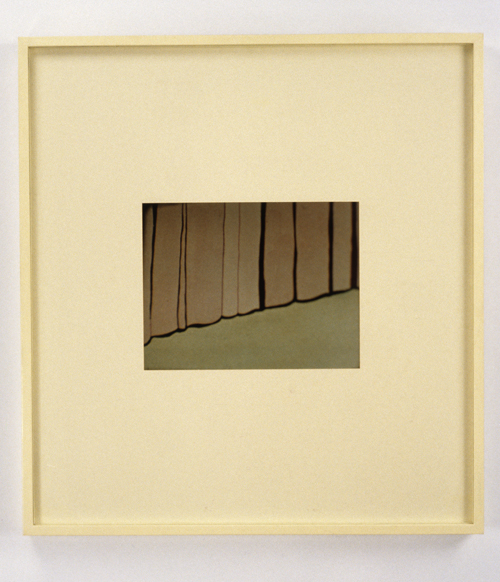

Image: Cartoon Curtain (Jennifer Bolande, 1982). Courtesy of the artist.

JB: Ha! Funny question. I’d been working with those things from the very beginning. My early jobs in New York were all in the film industry, mostly in post-production. I worked at a film lab as an apprentice timer, the person who does color correcting. One of the things I had to do was examine release prints on a high-speed film viewer called a Vedette. I’d look at release prints hundreds of times faster than you would normally watch film, checking for what they call “mis-times,” such as light leaks and flashes. Amazingly, you could detect these in a single frame even though it was going by so quickly. This particular lab was in Times Square; a lot of their bread-and-butter business at the time was soft-core porn, and cartoons for mail order. A lot of my early pieces, like Cartoon Curtain (1982), came out of that experience. Also The Porn Series (1982), which are cropped stills from 50s retro porn films by Irving Klaw. Watching them really fast, I noticed these moments of calm at the beginning or the end, with all of this “activity” in between. It was this kind of aporia, with just an empty set, before that particular kind of narrative ride takes place. [Laughs.]

JLM: These are displayed as photographs?

JB: Yes, they were photographed off of a screen. Mostly they were from the opening frames of films, which were cropped in a certain way to accent the area I was interested in, reducing each set to just a few elements. The cropping creates equivalence between set, character, and prop, and a kind of pregnant, ominous sense of expectation. The prints are very small and intimate.

JLM: These images seem to draw the eye toward details that are peripheral to the “main event.” Those details might not seem crucial to the film-viewing experience, especially in this case, but they are deeply important. It’s different to film a porn on this kind of a movie set, and to light it in a certain way, rather than in a blank white room. These details contribute to the viewing experience. I like that these images, like so much of the rest of your work, are dealing with things that are on the periphery and that go overlooked if we just focus on content. If you do that, you leave behind so much of what goes into our experience that makes it pleasurable.

Image: Porn Series (Jennifer Bolande, 1982). Courtesy of the artist.

JB: Yeah, that’s interesting. Porn films are updated all the time. They’re expected to look current, so there’s that element of fashion and interior décor. The Porn Series images are black and white and stripped of most of their identifying details.

JLM: What other jobs did you have in film?

JB: I worked for a few years as a negative cutter. I started to work as an apprentice editor, but they wanted me to work 60 hours a week for $8 an hour. I couldn’t, because I still wanted to be an artist, but I loved doing it. I loved the materiality of film, the smell of it, the process. I loved wearing the little white gloves. But I just couldn’t afford to go that route. I left it behind and found other ways of supporting myself. In my work, I start from wherever I am. Whatever jobs I have, there are things from those environments that go into the work. You were asking me about moving to California: I am so not interested in Hollywood movies, and I don’t care about movie stars.

JLM: Looking through the survey of your work, there’s a slightly analytical, slightly scientific way of looking at some of these technological devices or objects that are falling by the wayside, but it’s not entirely intellectual or scientific. There’s a very personal, experiential side to it, where your intuition leads you to things. The fact that you no longer go to the theater to engage with films in the way you used to, in the way we used to as a culture – brings up the question of nostalgia. Do you think nostalgia is a bad word when it comes to art?

JB: I kind-of do. I have to really distinguish what I do from nostalgia. It could look like nostalgia to the superficial eye, but I am in no way saying, “Things were better back then.” Of course you do think about differences between the past and present, through the technologies that we are all engaged in and through the acceleration of information and how fast we feel we have to move to keep up. The way I work, which is very slow and involves really steeping myself in experiences, and things over time – it’s hard to imagine someone developing a practice like this now. I wonder about the fullness and depth of engagement that people are encouraged to have, not just pedagogically, but because all of that’s there to be moved through. I have concerns about that. [Laughs.] There is certainly an elegiac quality to what I do, but that’s different from nostalgia. I read somewhere that the world can be divided into two kinds of experiences: things that are arising, and things that are passing away. I’m definitely oriented toward things that are passing away, but I try to attend to things that are arising too. The hardest part is being in the present moment, which is what I think I try to get to. I tend to be looking at what just passed, with the assumption that I probably didn’t catch it very fully when it was first arising. Our whole culture is so oriented towards the next new thing. I like to counter that and exercise the freedom to place my attention elsewhere.

JLM: Being in the present is essentially being in a moment of transition. Sometimes the thing that’s arising is forcing the other thing to fall away. In some religious philosophies, the idea of the present is supposed to be empowering. But in some of the ways that you’re describing it, it’s also scary.

JB: It is scary. It’s scary for all of us. I think that’s why every chance we have, we’re jumping into planning or imagining the future or we’re remembering the past, because we don’t really know how to deal with the present. The present is the only place where you can actually do anything. Or have an actual experience or perception. Maybe it’s scary because the present moment is always disappearing; it has to do with death. Having something be open – that’s the unknown. People want to foreclose that.

JLM: And that would give rise to the idea of nostalgia, the comfort of thinking that this thing, this object or technology, is comfortable and we can know it.

JB: Right.

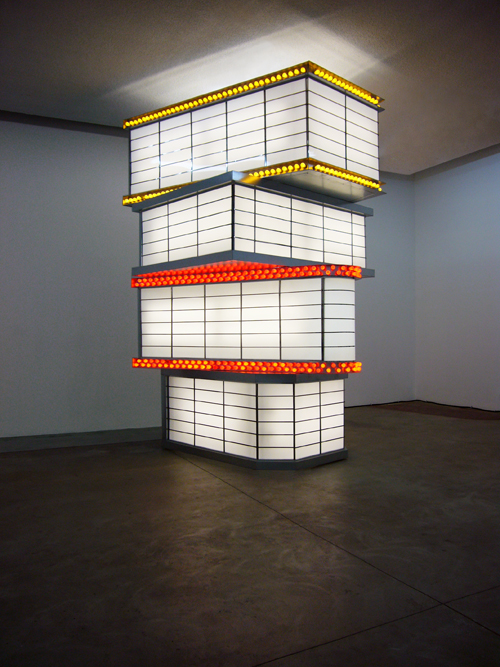

JLM: I want to ask you about one more piece that fits in here, a piece I really love, the Tower of Movie Marquees (2010). What was the genesis of that?

JB: This ties in with the Runaway Train story and photographing the title on the marquee in Times Square. I noticed an aging movie marquee in Times Square that had all these gnarled pieces of metal coming off of it. This was at a time when Times Square was really decaying, in the 80s. I had a fantasy about the marquee falling and crashing to the ground – a pretty powerful metaphor. That fantasy generated the piece and the (1987). The marquee had the title for Harry and the Hendersons (1987) on it. I fantasized that if it did fall to Earth, that fragment – “and the” – is what I would want.

Image: and the (Jennifer Bolande, 1987). Photo credit: Eeva Inkeri.

I’m interested in certain kinds of things that you have a bodily orientation to. We look up at movie marquees with a sense of expectation about what’s to come. They hold promises, in a sense. The Tower of Movie Marquees is a promise of – I had a phrase for this: “empty containers of yesterday’s promises.” So the marquees come “down to earth,” and then by stacking one on top of the other I can begin the process of climbing back up to the sky.

There was another movie marquee that I fell in love with. It was on 42nd Street. When I heard about the Times Square redevelopment plan, I tried valiantly to try to get it, seeing it as a rescue mission. I didn’t really know structurally how it worked. I just pictured that it would come off of the building, like a big found object. Of course, it doesn’t work that way; they’re integrated into the building. I was very much attached to the idea of using that particular marquee, and when I couldn’t get it, I gave up. Then, one day I read in the paper that they had removed all of the marquees in Times Square; they put them in one building and then the floor collapsed and destroyed all of them.

Image: Tower of Movie Marquees (Jennifer Bolande, 2010). Photo credit: Maegan Hill-Carroll.

JLM: So your prophecy came true.

JB: Yes, but it was liberating. Now that it was gone, I was set free to recreate it. I had taken enough photographs of it that it was easy to follow.

I went to Artkraft Strauss, the company that has made most of the signage for Times Square for the last hundred years, and they had stacks of movie marquee panels and parts, which I used to build the prototype. At first I constructed a two-stack, but I always imagined it being taller. In 2010, I made a four-stack. But I still want to go higher. I am searching for a home for this tower in public space. I do love Times Square, and there is a traffic island there that’s perfect – almost the exact same shape. But I think the piece would make just as much sense in L.A.

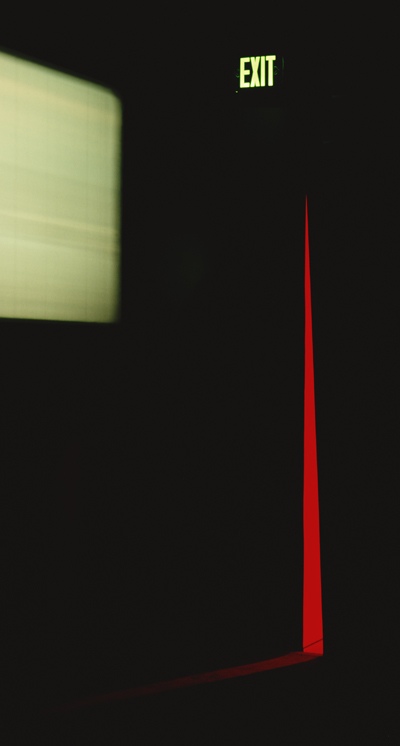

Image: Exit Triangle (Jennifer Bolande, 2010). Courtesy of the artist.

Published August 21, 2012

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

J. Louise Makary is a filmmaker and writer based in Philadelphia. She recently spent a year writing about the comic book version of the movie Grease (1978), and is now working on an experimental narrative film set at Colonial tourist site. www.jmakary.com

INCITE Journal of Experimental Media

Back and Forth