Interview with Sam Green

By Penny Lane

Utopia Part 3: The World's Largest Shopping Mall / Sam Green

While Gordon Gekko was making it big on Wall Street and Nancy Reagan was asking us to “just say no,” a disaffected teenager named Sam Green was hanging out in a 7-Eleven parking lot in East Lansing, Michigan, bored out of his mind. In college, he started digging on William S. Burroughs, hardcore music, and all the rest of the “rad counterculture” he didn’t know he’d been missing. Green says of the alt culture scene back then, “We all had an anti-corporate, anti-state-power kind of sensibility, but a lack of belief that things could really change.” He started to realize that “the shadow of the failure of the 1960s” hung over his generation, and he wasn’t too sure how to feel about it.

This question stayed with Green as he went on to study art at the University of Michigan (“I didn’t like art school… it seemed too solipsistic, too cut off,”), then journalism at UC Berkeley (“Journalism seemed a good way to engage with the real world”). While working for Fox News in Los Angeles, Green found his calling as a documentary filmmaker. His first film was Rainbow Man/John 3:16 (1999), an underground darling that premiered at Sundance. By now, he is best known for The Weather Underground (2002), which Green co-directed with Bill Siegel. The film is a remarkably even-handed portrait of the Weathermen, a radical sect that tried to overthrow the U.S. government in the 1970s. The film was nominated for an Academy Award and included in the Whitney Biennial.

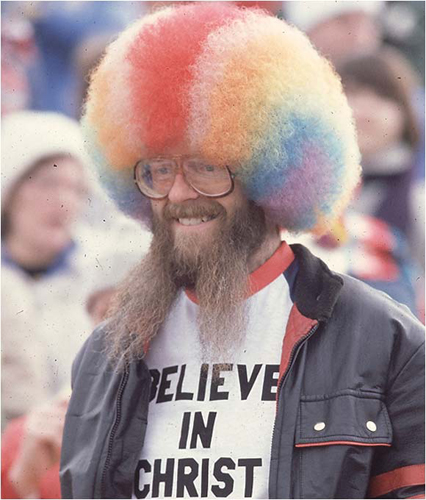

Green’s films have a kind of gentle irony: he makes cautiously hopeful films about the failures of other hopeful people. The Weathermen tried and failed to use terrorist tactics to bring about peace. The Altamont Music Festival was supposed to be the Woodstock of the West Coast, but instead it became a nightmare of bad drugs and grim violence (the subject of lot 63, grave c, 2006). Investors wanted to create the world’s largest shopping mall in China, but they ended up with the world’s largest ghost mall (see Utopia Part 3: The World’s Largest Shopping Mall, 2009). Rainbow Man/John 3:16, which follows the bizarre career of a man who tried to save the world by donning a rainbow wig and promoting Biblical scripture at sporting events, traces the same contours of idealism, hope and failure.

But even if his subjects are sometimes convinced of their own failures, Green takes a more nuanced view. Pie Fight ’69 (co-directed with Christian Bruno, 2000) documents an elaborate prank organized by a radical film collective at the San Francisco International Film Festival. The collective thought the prank would be a good fundraising tool. But it didn’t work, and the collective disbanded in frustration. The footage of the prank was discarded and forgotten–until Green’s friend, the filmmaker Bill Daniel, found it in an unlabeled box in the basement of Other Cinema. Pie Fight ’69 pairs the footage with an interview with one of the original pranksters. The glum tone of the interview stands in sharp contrast to the joyfulness and hilarity of the image; you can almost hear Green saying, “Okay, it didn’t work… but I really love your film.”

Rollen Stewart, the Rainbow Man

Penny Lane: Tell me about making your first documentary, Rainbow Man/John 3:16.

Sam Green: After I finished journalism school in 1993, I moved to L.A. and got a job working for Fox TV. My job was to find and license footage. It sounds funny, but I love licensing footage. Haggling and contracts and shit like that. I liked it, but I was still bored at work. I read something about the Rainbow Man, and it really just moved me for some reason. All of my films have come out of being touched or smitten or moved by an image or a story or a detail. With the Rainbow Man, I found out that before he totally went off the deep end, he had been homeless and living in his car in Los Angeles. T he idea of the Rainbow Man being homeless in a car… that detail really got to me. The more I read about the story, the more it affected me on an emotional level. Because of my job, I could call, say, MLB [Major League Baseball], and ask for footage from a particular game [that I knew the Rainbow Man had appeared in], and bill Fox News for it. [Laughs.] And that’s how I made the film. It was sort of a lark. I didn’t even know that there was like, a film world. It was just fun to work on. It ended up as a 42 minute film, and that’s the absolute worst length, right? [Laughs.] I just had no clue. But then it showed at Sundance, which was really surprising and cool. Then Craig Baldwin asked me to show it at Other Cinema, which I did. He gave me 50 bucks or something, a big wad of one dollar bills. Through [making] that film, I got my first glimpse of the underground film world, as it was called at that point.

PL: Tell me about interviewing Rollen Stewart, the Rainbow Man. That interview felt intensely uncomfortable.

SG: Well, before I realized I was even going to make this film, I had started a collection of Rainbow Man clippings and footage. I was just interested in him, so I wrote him a letter. He was in prison, at the California Men’s Colony in San Luis Obispo. I asked if I could visit him. He wrote back saying nobody had ever come to visit him, and it would be great. He was a great character, and I was really energized after meeting him. Then when I realized I wanted to make the film, I decided I should go back and interview him. When I met him the first time, he was really funny and nice and kind of light. But when I went back to do the interview, he was very tense, as you can see in the movie. He still believed that the world was about to end, so [this interview became] a way to get the word out. He was really distraught, and [at the time] that wasn’t what I was going for, you know? So I thought, “That is a disaster. Okay, never mind the interview.” But then I showed the footage to some other people, and realized that there was something really significant about the way he was not happy and funny. So in the end I used the interview.

PL: I’m glad you did! You moved back to San Francisco at a certain point?

SG: Yeah. The Fox News show went under. And I realized I didn’t want to do TV news. TV news was terrible. I decided I liked documentary better. Somebody told me that if you want to work in documentary, you got to learn how to either shoot or edit. So I learned how to edit. I heard that if you learned how to edit on the Avid, you can make fifty dollars an hour. I thought that sounded pretty great! I did learn Avid, but I never made fifty dollars an hour. [Laughs.] I edited a lot of bad docs for the History Channel.

Weatherman Mark Rudd, from The Weather Underground / Sam Green and Bill Siegel

PL: Your next big project was The Weather Underground, which you started in the late 90s. Why did you think that the story of the Weathermen needed to be revisited at that time?

SG: Most of the people I knew in the 90s were not into politics, or thought that [activism] was lame. I wanted to make a movie that would get some political ideas out there. But I knew that it had to be a story that would resonate with people that weren’t necessarily open to that. I loved the story of the Weather Underground. It sort of embarrassed me and thrilled me at the same time. I also knew that it was sexy enough to get people’s attention: you know, good-looking people bombing buildings and running from the FBI. But at its heart, it’s a totally radical story with radical ideas and many different critiques of state power that still resonated with the world today. There was a sort of moral ambiguity that interested me. The Weather Underground people were in a shitty situation, a desperate situation where there were no good or obvious paths in front of them, and they acted. I couldn’t make up my mind on whether what they did was right or not. And that kind of morally ambiguous story, for me at least, raised questions about the world today, and it did it in a complex way. I liked that.

PL: How did you find and convince the former Weathermen to participate in the film?

SG: That took a long time. At first, they all said, “This is a terrible idea. Don’t do it.” There had been very little done about them, and what had been done was really sensationalized. It’s super easy [to sensationalize the story], if you play down the political context and play up the drugs and sex. So they just assumed that this film was going to be like that. It took a long time for [the subjects] to get to trust us, and know that we wanted to take it seriously. What we said was, we’re not going to do a hit piece and we’re not going to do a puff piece. It took about two years before we felt like, “Okay, we have enough people who are willing to do this, that the movie will work.”

Meredith Hunter in the crowd at Altamont, from Gimme Shelter by the Maysles Brothers.

Still from lot 63, grave c / Sam Green

PL: Your follow-up to The Weather Underground was lot 63, grave c. Was it intended as a kind of post-script to the feature?

SG: When I was doing research for The Weather Underground, [I found that] Altamont is cited over and over again as the end of the 60s, and people often point to the moment when Meredith Hunter [was murdered at Altamont] as the exact moment when that era ended. So he was sort of famous, right? But I had never even seen a picture of him. After the dust had settled, it was one of the things I was still curious about. I started to poke around trying to learn something about him, and there was just nothing. There was a newspaper article about how he had died during the trial, but that was about it. I figured out what cemetery he was buried in, and I went there, just to see his grave. And the film basically [replicates] the experience I had, because the experience had really affected me emotionally. [Hunter’s unmarked grave] was in the shittiest part of the graveyard, right next to be a big fan cooling system. And so the film is really a poem, in a way, about that experience and that feeling that I had.

PL: I remember you telling me that some people that saw your film ended up donating money to give him a gravestone. Did you intend that outcome when you made it?

SG: No, I didn’t intend that at all. I dedicated the film at the end to Sarah Jacobson, [a filmmaker and friend] who had died not that long before. I was feeling kind of sad that not that many people knew her films anymore. [Her career] was right before the web took off, so she doesn’t really have much of a web presence, and so she has just been… forgotten, to some extent. I had been thinking about that when making the film, that time erases people, erases even their traces. It’s just kind of sad. So the film was really an expression of that feeling. I never thought that someone would want to give him a headstone, but yeah, that’s what happened. Different people saw the film and offered to give me money, and I gave some money. It was nice. For some other documentary filmmakers, they might say, “I got somebody off death row!” or “I changed a law!” But probably the most I’ll ever accomplish is that I got a headstone for Meredith Hunter. [Laughs.]

The Universal Language / Sam Green

PL: Tell me about some of the other short films you are showing at Anthology Film Archives on November 8th [2010].[1]

SG: Clear Glasses is a film I made in 2008. Mark Rudd, who was in the Weathermen, was wearing these dorky tortoiseshell glasses when he turned himself in. I remember being struck by these glasses in the news coverage I’d seen–they were just so weird. And then, one day I got a package from him, years after I’d made The Weather Underground. I opened it up, and there were those fucking glasses. I was just delighted and flummoxed. I loved them. I made the piece because I felt like the fact that I would love these glasses so much was connected to my impulse as a filmmaker. It’s kind of a little ditty about that. I’m also showing Utopia Part 3: The World’s Largest Shopping Mall, which is about this huge Vegas spectacle of consumption in China, but [the mall] ended up being a total flop.

PL: Another failure.

SG: And another big idea. It’s part of this larger project I am doing about utopia.[2] With the Utopia project, I wanted to [tell these four stories] that are about utopia [in one way or another]. I feel that they, when added together, create this larger emotional truth about who we are today, and how history lingers with us and shapes our sense of hope and possibility. I’m also showing a new, longer piece from the Utopia project, a half-hour work-in-progress about Esperanto. The Utopia project is not a history lesson, or a hard analysis. It’s more about feelings and ideas, and a complex knot of things that are not easy to talk about, not easy to think about, or to come up with easy answers about. It’s more like a poem using different through-lines from the history of the past century. Hopefully, it adds up in a way that it’s not easy to summarize.

PL: Do you think of yourself as an activist?

SG: No, that’s a good question . I’ve always felt like there is a tension between making art and activism. For me at least, I think that activism, in some ways, is about simplifying things. Getting people to do this or that. And art, the kind of art that I like, is about embracing complexity and nuance. And so I kind of think they don’t always go so well together. So, I don’t see myself as an activist. I know a lot of activists, and I admire them. And I know that I’m not out there doing the work. In some ways, I couldn’t justify calling myself an activist. I see myself as a documentary filmmaker who makes work that is political.

1. Sam Green will show a selection of his short films, including a brand-new work in progress about Esperanto, at Anthology Film Archives on Monday, November 8, 2010, at 7:30pm. This event is presented by Flaherty NYC, a monthly series of risk-taking documentary films sponsored by The Robert Flaherty Film Seminar and programmed by Penny Lane.

2. Most recently, Sam Green has teamed up with the musician Dave Cerf to create Utopia in Four Movements (2010), a “live documentary” event pondering “the battered state of the utopian impulse at the dawn of the twenty-first century.” Green intends Utopia to be experienced only as a live event. “It’s about utopia,” he says. “Do you really want to watch this alone on your iPod?”

Published November 1, 2010

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Penny Lane is a filmmaker and video artist whose work has shown at International Film Festival Rotterdam, Images Festival, Women in the Director’s Chair, AFI FEST, Antimatter, Impakt, and the Museum of Modern Art’s “Documentary Fortnight.” Her video-essay The Commoners (2009), made with Jessica Bardsley, appears in the second issue of INCITE. www.p-lane.com

INCITE Journal of Experimental Media

Back and Forth