Interview with Jim Finn

By Penny Lane

Jim Finn’s idiosyncratic shorts have been a fixture on the experimental film and video scene for over a decade now. In the past four years, he has also released three feature films with essentially no budget–an astounding feat. And they’re good, really good, g ood enough to watch and enjoy repeatedly. In fact, if you don’t watch them several times you might just miss their incredible craftsmanship.

Interkosmos (2006) is a Communist love story based on Finn’s “What if?” interpretation of a 1970s East German space program. The film looks a lot like a 70s-era documentary, save for the musical scene s. La Trinchera Luminosa del Presidente Gonzalo (2007) is a painstaking re-creation of a day in the life of a female Peruvian inmate, circa 1988. The prisoners are members of a brutal Maoist insurgency, The Shining Path, whose rigid adherence to ideology terrifies and strangely impresses. The Juche Idea (2009), Finn’s best film yet, details a video artist’s attempts to update the antiquated film theories of Kim Jong-Il while employed at a North Korean artist residency (or is it a work camp?). The film is based both on Finn’s fantasy of what a North Korean artist residency might be like and the true story of a South Korean filmmaker who was kidnapped and forced to make propaganda films for the North Korean dictator. Together, these three features form a fascinating (and hilarious) trilogy about an increasingly nostalgic longing for Communist revolution, the poetic possibilities of propaganda, and the limitations of historical documentary.

Although his films are unmistakably, fiercely political, Finn is anything but an ideologue. He embraces and even encourages confusion – the propagandist’s worst nightmare. I wanted to know more about how Finn squares his strong political leanings with his open-ended approach to filmmaking. The morning after a February 1st screening of Finn’s work at the Museum of Modern Art, we met at the Ace Hotel, where we each downed about six cups of Stumptown Coffee. This interview has been edited slightly to remove (most) traces of the ensuing caffeine-induced insanity.

* * *

PL: Can you share some of your pre-filmmaking background?

JF: I was born in 1968 and grew up in the 70s and 80s in St. Louis. The first president I was excited about was Jimmy Carter. I went to a lot of different Catholic schools – I had the St. Joseph nuns, the Jesuits, the Christian Brothers, and the Benedictine monks. Then I went to a small Jesuit college, Fairfield University, for a couple of years, and moved from there to the University of Arizona’s creative writing department, where I studied poetry with Barbara Anderson, Jane Miller, Terry McMillan and a number of other writers. I got into poetry , but, I did n’t have any concept of how to build a career writing poetry. I was like, I have to read these magazines that I don't really like; I have to do these public readings which I like, but which I don't know how to set up. And, I’m supposed to hang out alone a lot, or something. I didn't really get it. [Laughs.]

S o I went and did political work for a couple of years. Lived in Latin America, worked with a group called Witness for Peace, working with Guatemalan refugees in Chiapas during the Zapatista uprising. I did that for two years, then moved to Chicago in 1995. I had taught myself photography in Latin America, and when I got to Chicago I really jumped into photography and was still writing a bit. I fell in with a lot of young filmmakers and musicians, a gang of artists who became friends and collaborators, like Jeff Mueller, Dean DeMatteis, Jim Becker, Nicole Emmons, Dana Carter, and Butcher Walsh.

I almost left Chicago– it was too fucking cold and I didn’t like it. But instead of moving, I got a small grant, maybe $900, in 1997 to make a short 16mm film, Sharambaba, which ended up costing around $3000. I shot it, and it looked like a goddamn student film; I did not like it at all. I didn't start making films until I was 30, and I didn't feel like a student filmmaker, either. So I put it [Sharambaba] on the Steenbeck and started running it and rewinding it backwards and realized the film was better and funnier backwards, which worked because I had an Ecuadorian-American actress who spoke with an accent that sounded good backwards. English is so staccato, whereas Romance languages are more mellifluous, so backwards and forwards they kind of flow into each other. So I re-wrote and gave her all the best lines in subtitles , such as “ Marriage is like a mad dog on a piece of wood, floating on a river. It runs back and forth, frantic, thinking how to get off. And yet it’ s happy.” Although I shot the film in 1997, I didn't screen it until 1999. I edited the film for two fucking years, a three-minute film .

PL: So poetry was an important part of your films from the beginning?

JF: Yes. My whole idea was I wanted to make something that seemed like fiction, but was really a kind of poetry. And I felt like short films worked really well with that concept. Trying to make a short film with the exact rules of narrative feature filmmaking is, in a sense, cheating the medium.

PL: Were there people that were instrumental in discovering and promoting your films along the way?

JF: God yeah. All the programmers at THAW [in Iowa City], New York Underground [Film Festival], Rotterdam, Chicago Underground, Cinematexas, Impakt, people like that. I had this phenomenon at many points in my life, where I would make this work, and there were key people who would be really excited about it early, like right away . Then it would take a while for other people to catch on. It happened to me with my poetry, then with my short films. After a while, I got this confidence. I also read a lot of guerrilla theory, and I have this idea of a people’ s war that’ s not going to happen overnight. You just gotta keep doing the thing that you believe in and eventually–

PL: How do you fund and distribute your work?

JF: Well, in Chicago I had a system where I worked three part time jobs and got a lot of favors. I’ ve always been of the mindset that you have to, if you're working outside the system, then you have to build an alternative community. And rely on other filmmakers too. Most of my films have friends working on them, and I've also acted or shot video or helped edit other people’ s films as well .

I also got a couple of small grants from the city of Chicago. They weren’ t that big but they helped. I would go for all the big ones everyone goes for, and I don’ t know exactly why I never got any of those. Part of the problem is that I build my films a lot during the editing, and I have a hard time articulating my vision ahead of time.

There are basically two ways to get funding for a film: One is to have a very clear idea of what you’re doing in advance; the other is to have a very clear theoretical framework so that you can explain to someone why you’re making a weird-ass experimental film. I’m not very good at either of these . It’s taken me a long time to figure out why I even do what I do. Anyway, that helped to keep me broke and non-funded.

Interkosmos / Jim Finn

But with my first feature Interkosmos, I made it and started selling DVDs like crazy. And I went on tour with my shorts and made a little bit of money from screenings. I had gone on two national tours with my short films so I figured out a lot about self-promotion. I turned that money around right away and into La Trinchera Luminosa, my second film, which was cheaper to make than Interkosmos. During this time I went and got my MFA, and put all my credit card into student loans. Then I decided to make those two feature films in grad school, which I treated as a kind of a residency where I could do whatever I wanted. I made up names for classes like “Postmodern Socialist Realism,” “Biomedia Study: Insects,” and “Luminous Visions in Video.” Those are like really the titles on my transcript. [Laughs.] But I didn’t work while I was in school, so basically I racked up about thirty grand in debt. However, I came out with three films and an MFA, and since I had health insurance I also got my knee surgery, which I needed very badly.

PL: All three of your feature films relate to ideological Communist societies or social movements: East Germany in Interkosmos, Shining Path in La Trinchera, and Kim Jong-Il’s North Korea in The Juche Idea. How did you research these societies and movements, and how do you use the ideologies in writing and creating the films?

JF: With Interkosmos, I was interested in how these Marxist-Leninists imploded. They imploded at almost the exact wrong time, at the height of the neoliberal capitalist model, after Reagan had supposedly proven how great Friedman economics were. So these places became the great experiment for Friedman economics and it was a total fucking disaster: young women were forced into prostitution, people got tuberculosis, all this shit. With Interkosmos, I wanted to think about what could have happened if there had been some kind of transition to a center-left, democratic model. I thought about this utopian system within a system. And I thought, well, that system was actually so corrupt and autocratic that it never could have been reformed in that way, but if they had launched into space, maybe there could have been this space utopia thing.

I also like the idea of the genre film that can be viewed as a genre film, but that also has another, deeper significance. I like to work with a genre system, where you have rules to follow. So I create my own studio system. With The Juche Idea, I created my own North Korea studio system where I had to learn the rules in order to subvert them. Or, I created the Maoist Shining Path system that I subverted, and the East German documentary style that I then subverted. In a sense, this method is sort of similar to what Fassbinder did with the melodrama, or what Buñuel did with Simon of the Desert (1965), or Pontecorvo with The Battle of Algiers (1966), where you have seemingly one kind of film and then it goes in a different direction. I feel like I’m referencing that tradition and also bringing in other weird elements, like poetry and video art. But the main thing is, with all three of these films, I could never shoot anything that would show the system to be corrupt, because they would never allow that.

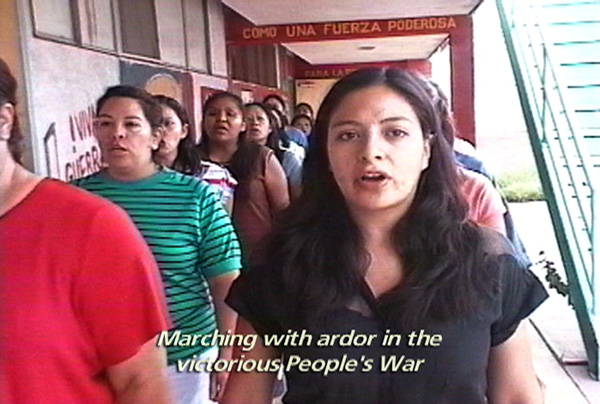

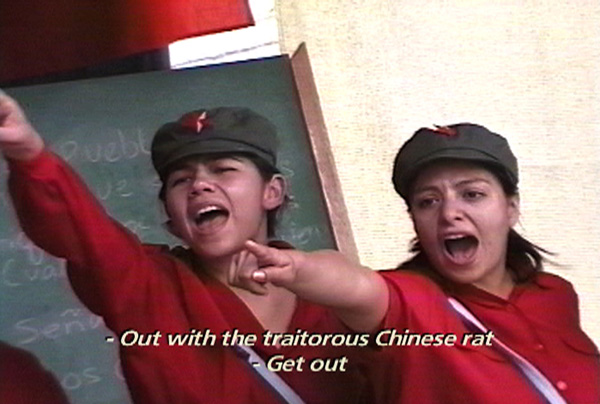

La Trinchera Luminosa del Presidente Gonzalo / Jim Finn

PL: Why did you approach the Shining Path material in the way you did? It’s very different from the collage styles of Interkosmos and Juche. It’s more like an observational documentary.

JF: I wanted to create it like it was a video I found in a market in Peru. I had seen these BBC documentaries about the Shining Path, and they would use this raw footage of them marching or whatever, but then they always cut away to an analysis of the group. But I wanted to see a self-criticism session, stuff like that. There’s this idea that after you see a documentary you can say, “OK, great, now I get that, I understand that culture or group or society.” And you know what, you don’t. How can you get it? This is a whole phenomenon–there was a civil war in this country for ten years, and you can watch a documentary for an hour and feel like you understand it? That doesn’t make any sense. Trying to jump into this other language and ideology and culture and history is really hard, so I felt like creating an intense thing where I’m playing by their rules: Now they get to talk, they’re going to explain their dogma and we’re going to have to listen. The first edit was 70 minutes of pure dogma and it was brutal, man. But I wanted it to be brutal. I wanted it to be immersive. Though the final edit is 60 minutes and it is a bit more reasonable.

As someone who grew up in Catholic schools in the 70s and 80s, you can appreciate this idea of having an ancient, rigid ideology where everyone else in the world knows you’re wrong, but you know you’re right. There’s just something about that idea, that things are fucked up and there’s this capitalist storm around you but you are a redoubt. That was appealing to me. And the Shining Path, I had been thinking about for ten years. In the States there’s this idea of the pure, good Left: Che Guevara, the Zapatistas, Allende, who’s the saint of the Left in Latin America. Then there’s the bad Left of Pol Pot, the Shining Path. So I thought, well, who’s making these judgments? Let’s look at the bad Left, the really nasty Left. I wanted to think about who gets into these movements–the young people trying to figure stuff out, idealists. I wanted to make something not sympathetic exactly, but from their perspective.

Interkosmos / Jim Finn

PL: How did Interkosmos come to be? Did it start as a feature, or did it evolve?

JF: It evolved. Interkosmos was a Soviet program, an international space program. The idea was that Americans had this great space program, but they're into American nationalism and imperialism and all that. And so the Soviets, even though they were also imperialists, pretended like they were really international Communists, so they had Vietnamese cosmonauts, I think there was one North Korean cosmonaut, a Mongolian cosmonaut, Syrian, Indian, and East German cosmonauts. No one spoke German in space; everyone spoke Russian. So when I was making the film, I had the idea of a utopia where everyone spoke different languages.

Before Interkosmos I had made Wüstenspringmaus (2002), which was about the history of gerbils and capitalism. And I wanted to make this new film, which would be the history of guinea pigs and Communism, like a sequel. I had the idea of guinea pigs as the international youth symbol of Communism, and that they sent them into space on this mission. But then I was like, well, why would there be guinea pigs and no humans? And if there’s going to be humans, they have to have a capsule. Obviously! Originally I was going to make a 12-minute film with these models and the guinea pigs. Then I decided on humans, and it got to be 20 minutes. And I thought, well, if I’m going to go through all the trouble to make a space capsule, I gotta make this thing longer. And then I was on tour in Houston, and these guys were like, “Oh, you're making a space movie? We have all this NASA footage this guy left at our TV station.” And the Goethe Institute asked if I needed some electronic equipment, because they were decommissioning all their 80s stuff. Joe Bristol, my art director, had some lumber left over from an Ace Hardware ad. So it was like that. I pieced it together. A lot of people helped.

It took forever, man. And I had talked about it around Chicago in bars and people were asking about it, “Where's your space film, it sounded great man, are you ever gonna finish it?” I made that mistake, of talking about your project before it’s done. [Laughs.] I didn't know how long it was, it just kept getting longer.

PL: It seems like your films, both the shorts and the features, require multiple viewings. I can only speak for myself, obviously, and some folks I’ve talked to. I like them the first time because they're strange and entertaining, but I don't feel like I really get them until the second or third time. I watched Dick Cheney in a Cold, Dark Cell (2009) three times. The first time I was too busy asking myself, “What’s going on here? What is this filmmaker saying?” It was just so strange and shocking that I didn't know what to make of it.

JF: But it’s kind of funny, right?

PL: It was hilarious! But I needed the second viewing, when the shock and original surprise of the strange form of humor had faded, to see it analytically and feel like I understood what you were doing. Does that surprise you?

JF: Well, part of it is due to the fact that I came from a poetry background, which is more of a rarified, esoteric audience. And I’m also kind of against the fast food idea, where you’re like “That tasted great!” and then you feel kind of dirty, like “Did I like that?” That’s the worst feeling.

On the one hand, the films can be demanding, but on the other hand there’s stuff like the Oleg scenes in The Juche Idea. I mean, I laughed out loud at my own movie again last night [at MoMA]. The guy is just a genius. And the way the writing went, and Sung backing him up, it just blows my mind. Also, if you have the ability to make people laugh, that’s basically the equivalent of grabbing someone by the balls in the film world. You have them, they’re not going anywhere, if you can make them laugh. If you can make someone laugh out loud multiple times, that is fucking gold. So what I then do is go in this other direction, to dry political commentary.

PL: I guess what I’m getting at is that you assume a fairly sophisticated audience. For example, you don’t provide background information. You just kind of plop us into a situation and ask us to come along.

The Juche Idea / Jim Finn

JF: Well, here’s the fact: When I go to make the movie, I have all this background info. I want to get all the historical information in there. And I start to do it, but there’s always so much exposition that it slows everything down. A lot of this stuff you can just read on Wikipedia, or you could watch a documentary about North Korea or the Shining Path. So I realized that the more interesting thing for me is this emotional connection to the people, the ideology, all this sort of stuff. So I set the stage as if you have this background already, and I ask the audience to just hang with it–that’s why I throw the audience some fucking bones. Like, I’ll have this long dialogue going back and forth, and you’re like what the fuck, you’re starting to get lost. Then I’ll stop and go into a musical number, so it doesn’t have to be a horrible marathon.

PL: Are audiences ever confused by your films? Do they misinterpret things?

JF: Well, sometimes they don’t know what’s real and what’s not. When they don't know that, and then find out it’s fiction, there’s that feeling of, “Oh, it's a mockumentary! I’ve been fooled!” I don't see my work as mockumentary. I feel I’m doing this other thing, creating a genre structure and subverting it, playing with the fiction-nonfiction line.

But also, because I’m an American white-guy filmmaker making films about other cultures, it’s kind of a dangerous ground. I could be seen as making fun of someone else’s entire culture or social movement. I was told in Venezuela, by one filmmaker, that I had somehow made a film that mocked every Latin American revolutionary movement. This was an ultra-leftist filmmaker, and he didn’t like me. Then an ultra-rightist filmmaker that was there told me that I should make a History Channel documentary with the footage I had, something like that. Obviously I wasn’t pleasing either of those two. Politically I feel my films are on the left, but they’re critical of the left, too. So that adds another element of potential confusion. When I made Interkosmos I had this idea that a lot of Communists might really love it; or I thought they might criticize it, I didn’t really know. A lot of Marxists really don’t like what I do. They’re not excited about it. They’re not into it at all.

PL: Because you're not an ideologue?

JF: Maybe. Also, there’s this idea that if you’re criticizing Communism, you must be doing it as an excuse to prop up your own dead, decrepit, Capitalist system. I mean, why am I using my talent to go after and take apart these easy targets of Marxist-Leninism, when I could be using my talents to take apart these ideologies that led to the Iraq war, which I also still kind of do, with some of the shorts and stuff.

PL: You said that you basically see your films as coming from the Left. Why do you choose material or topics or stories that make the Left so uncomfortable?

JF: Well, I don’t go into a film thinking I’m going to elucidate some subject. I want to understand it myself. I’m trying to work through these ideological systems, too.

Part of using Marxist-Leninist ideology is that it allows me to jump into other cultures and other languages. Part of the reason I can use this weird poetic language in the films is that it’s not in English. If someone spoke that way in English it would sound like irony. Whereas when my characters do it you wonder, well, is that the way they spoke? I guess maybe it is; I don’t know that culture or that ideology. It’s part of a triple separation: a lot of the characters are women, so there’s a gender separation. Then there’s the political separation of the Communist system. Then there’s a cultural-linguistic separation. Conveniently that lets me use my weird poetic language, where in some other country and political system people might actually talk in metaphors like this.

La Trinchera Luminosa del Presidente Gonzalo / Jim Finn

There’s nothing wrong with being a dissident in the United States and making films about how fucked up our system is; actually, that would probably help you with grants, especially in the Bush years. [Laughs.] But I felt, in a way, that I was trying to elucidate some of our own ideological traps that we fall into even now, that in some way you could read the present into these films, which are about systems that have already collapsed in some cases.

I really did have this fantasy that somehow, for instance, a Cuban film department would hear about me and invite me. But they’re not going to. If you’re making a film that’s experimental and critical of the autocratic systems of the Left and Capitalism, you're muddling the message; it confuses people. As opposed to a kind of orthodox Marxist filmmaking in the U.S. or Europe where your thesis, your message, your criticism has to be clear. I kind of feel like, what’s the point? These critiques have been happening, these films have been made, and yet here we are. As soon as someone fucking blows up a building, we can just go back to pretending we’re British Imperialists.

PL: No matter how many dogmatic lefty movies get made.

JF: Yeah, exactly. So I wanted to work without it. I just feel like it’s a trap, so I try to invent my own systems.

PL: One of the fun things about watching your films is that there’s all this text, and as a viewer you know a lot of it is appropriated, but it’s really hard to tell where your writing starts and where the texts end. Do you consciously find ways to mimic or parallel the tone of the found materials?

JF: I’ll have a line in my head like, "Capitalism is a kindergarten of boneless children. It looks good from the outside hallway but once you get closer you can see how squishy and rotten it is.” I can’t remember the exact fucking line right now, but I had it in my head and I thought it was really funny, so it made its way into the film. But how will anyone accept a line like that? A lot of the work is establishing the language up to a point where I can get away with a line like that. So I’m trying to set a tone where I can slip those kind of lines in. There’s a certain humor in my films which is laugh-out-loud funny, and there’s another kind of humor that’s more like, “Wait, what just happened?”

PL: How do you use characters in your films?

JF: The main characters in all three of my features are women, and they’re sort of like Greta Garbo in Ninotchka (1939): Stalinists who come to the west judging the Capitalist countries and sticking with their own ideology. All three are revolutionary females. But there’s sort of a crack in the facade. In Interkosmos, I built the love story around the guy who’s kind of a quasi-Communist, he just wants to sing his crappy capitalist love songs, and she’s judging him or maybe she’s just teasing him a little bit because there’s this flirty thing between them.

I’ve been held hostage by bad video art, or difficult experimental film where you don’t know where the fuck it’s going; but I feel like if a film’s structure is difficult, a character that we can relate to and grab onto and be interested in can help mitigate the difficulty of following the plot. I’m not giving people a lot of traditional suspense; you’re kind of thrown into this situation and you don't know exactly what’s going on, so the characters help ground you a little.

The Juche Idea / Jim Finn

PL: Jung Yoon’s a really great character in The Juche Idea. Of everyone, she seems most like your alter ego. Do you think that’s accurate?

JF: That's interesting. Yeah, she is sort of like me, a Stalinist alternative me, or–

PL: Like if I asked you, “How do you feel about making films in a Capitalist society?”

JF: Yeah, right, “It's like building a homemade floating barge in the bay, people come by and give you bits of carpet and lumber, and then when it's time to launch the barge, everyone's off watching the cruise ship spread its diesel bilge and raw sewage across the open ocean.” [Laughs.] The fact of the matter is, in the U.S. there’s this concept of artistic success, and even if you’re doing well, you might be broke, you know? You might have stepped on so many friends along the way that you've ruined all your friendships. I don't want to say everyone’s clawing their way to the top, that’s not exactly what I mean, but there is the concept of what it takes to “get there” as an artist, and what you have to do, and maybe when you get there your original goals have been lost.

Young artists all have that idea, they imagine what it would be like to be an artist and have all your basic needs taken care of, all your food and stuff. Like, oh, I want to move to Berlin, or some magical other place like New York–

PL: Or Canada.

JF: Right, Canada. But seriously, how many people move to what they think is some magical place, where there’s support for the arts and where you don't have to struggle to eat, where you can just make your work, which is already a struggle. It’s a huge struggle to figure out and realize your vision in some kind of a smart way. On top of that you have to figure out how to fall in love, pay the rent, live a life, maybe have a little bit of fun. And so, I thought maybe there’s a residency in a Communist country where they provide you with the space, but then there are these limitations too. Like you have to make weird propaganda films, but maybe you can have fun with that. And you have to shovel chicken shit.

PL: I know you have to run, but thanks for your time, Jim! Will you please sign my copy of the Kim Jong-Il’s On the Art of Cinema?

JF: Sure, man.

Published April 3, 2010

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Penny Lane is a filmmaker and video artist whose work has shown at International Film Festival Rotterdam, Images Festival, Women in the Director’s Chair, AFI FEST, Antimatter, Impakt, and the Museum of Modern Art’s “Documentary Fortnight.” Her video-essay The Commoners (2009), made with Jessica Bardsley, appears in the second issue of INCITE. www.p-lane.com

INCITE Journal of Experimental Media

Back and Forth