Jawa Manifesto *

By Tasman Richardson

Jawa: Those scavengers of modern myth, stealing and salvaging

technology and remodeling it for their own purposes.

Nomadic pirates of the alien wasteland.

The term “Jawa” stems from the Star Wars mythology of George Lucas. The Jawa were the scavengers of the desert planet Tatooine. They lived by stealing and re-wiring old technology for personal use and for profit.

One of the earliest tenets of Jawa video was the insistence on appropriating recordings; taking from the existing pile of video detritus instead of making new recordings. Television and film had come to inform much more of our time and consciousness, so that these shared “personal” experiences could provide a fast and effective source of content; a cultural dictionary.

The television screen is the retina of the mind’s eye.

Whatever appears on the television screen

emerges as raw experience for those who watch it.

Therefore, television is reality and reality is less than television.

- Videodrome

As in any form of written or verbal transmission, we do not reinvent words with which to communicate, but rather reorder the familiar, thus allowing for a free-flow of idea-exchange. The value of any word in and of itself is null, but rather can be used to compose a grocery list or a poem, as the author chooses. Only then are they infused with value. Therefore the available visual dictionary, which is filled with easily recognized symbols, can communicate vast ideas with immediacy.

Images of sex and death were early, primal examples used by Jawa members to stimulate. Over time this has evolved into the use of any emotionally charged or culturally loaded pop imagery. The best uses are those that can convey an entire storyline in a 30th of a second. For example, a single frame of Darth Vader instantaneously evokes the whole mythology of Star Wars and that character. This, in turn, calls to mind significant elements of Greek tragedy because that is its source origin, as described in Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with A Thousand Faces. The symbol that the Jawa editor appropriates imparts all the ideas it first appropriated. A theft of a theft of a theft.

Beyond the importance of this widespread relevance was the essence of the medium itself: editing. The technique of placing things in an order (in video, clips in a timeline) and, in particular, re-ordering that which already exists was explored by William Burroughs and Brion Gysin. They used the cut-up technique in writing to reveal the truth or the essential content of earlier work by reducing it through a series of edits.

The permutated poems set the words spinning off on their own;

echoing out as the words of a potent phrase are permutated

into an expanding ripple of meanings which they did not seem

to be capable of when they were struck into that phrase.

- The Third Mind (Burroughs/Gysin)

Jawa is focused on the same technique with breaking and re-ordering visual/aural symbols. An example is attempting to mix together disparate cultural symbols to see if they can be merged into a recombinant work. Early on, Jawa attempted to discover what happens when symbols from religions, occult images, and global popular culture are fused. Would the result model the way a homogenous culture would look or would it only compare symbols that were resilient, remaining separate and unique?

An offshoot of Jawa was to re-mix the source material from the work of other appropriation artists. Even though multiple artists would use the same material, it would be infused with their own style and intent. The edit, or the artist’s particular gesture, gave the work its unique value. A video with an image of Darth Vader does not tell the story of Star Wars; it is given new life with each iteration of new context. Meanwhile, the Burroughs/Gysin effect could be observed through overlapping themes, which surfaced and infused the final piece with further meaning.

Fig. 1: Still from Attack of the Clones (Tasman Richardson, 2003), a Jawa video commissioned for the FAMEFAME competition The 6th Day, in which all participants were forced to use the film The 6th Day (2000) as their source material.

Fig. 2: Close inspection of Roy Lichenstein's paintings reveals flawless uniformity.

An earlier example of this same exploration of the fundamental nature of the artist who chooses a technology-focused medium can be seen in the work of pop artist Roy Lichtenstein. He said, “I want my painting to look as if it has been programmed. I want to hide the record of my hand” (see Figure 2).

However, he can only achieve the look of mechanization he wants by crafting it with those hands he wishes to conceal. Jawa works to approach machine-like perfection but can only improve upon it with the human ability to assess and craft every aspect of the video.

So, in Jawa editing no automation is used. It relies heavily on straight cut and cut-and-paste methods. There is no software triggering the edits or automatically synchronizing pictures and sound separately. Nor does software automatically correct pitch and speed to create rhythm or melody. All of the musical elements and the layered visual compositions materialize through the slow method of adjusting, placing and compositing each clip one-at-a-time.

The composition of music and imagery works together to compound the experience of both seeing and hearing at once. In Jawa there can be no separation; the two sensations are integrally bound: what you see is what you hear and what you hear is what you see.

Jawa attempts to make all of the information necessary to the audience. Entire films are reduced to their essentials, sometimes no more than a single frame. Further, it attempts to overload the audience’s ability to experience the work on an intellectual level.

It is able to do this because what we see on video is processed in the same way as what we experience in life. What we see, whether via a recording or not, is perceived as emotionally real by our brains. Consciously we can tell ourselves that an image is not real; but, nonetheless, the sight of sex is arousing and the affect of watching violence is to become afraid or enraged, etc. We respond emotionally as if the stimulus were real.

In Jawa, the early use of sex and violence was designed to catalyze an emotional response in the audience, making them feel something real through the careful uses of artifice and speed. The goal: to present stimuli faster than the audience can logically process, comprehend, accept or reject. The cultivation of the emotional response was seen as the most genuine response one could seek out in the viewer. The intensity of the edit in the work drives out the viewers’ ability to edit their own response to it.

To create the desired information overload, the liberal use of jump cuts (jolts) contributes to re-focusing the audience, as in advertising. When the audio and video are simultaneously and constantly cut and replaced with new information, the viewer is repeatedly called back to fully focused attention on the work in front of them.

A further tool in this desire to maintain the constant attention of the viewer is the musical editing. All of the information contained in each video is given an appealing structure in the form of music. It is difficult to ignore as rhythm draws people in and it is employed to reinforce the intended meaning of the recombinant visuals. As clips combine and layer a clearly recognizable musical foundation is developed and repeated.

It is then regularly interspersed with new clips, which stand out as new focal points, catching the audience’s attention and directing their digestion of the video while still allowing the viewer to spot and match the video source for everything they’re hearing.

The focus on immediacy and deliberate manipulation of the viewing experience is summed up in the objective that every Jawa work should convey the feeling to the viewer that they are “in the now and only now” Everything is reduced to the moment being watched. Moreover, because of the symbols and techniques that play on the subconscious, the viewer should get the sense that they are sharing the daydream of the person who crafted it. Non-verbal communication and direct, shared experience are the aims.

In this way, Jawa videos are somewhat like pharmaceuticals; designed to alter emotional and cerebral states. Early Jawa theory posited this transmutation could only be executed via a single channel experienced by a single person. Ideally the setting would be intimately familiar; even the viewer’s own home. One project involved distributing Jawa videotapes for free by leaving them in random mailboxes in the hopes that the curious would take them inside to take them in.

Fig. 3: The media collective FAMEFAME (2002-2007) used events like this one, Videodrome 2, at the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art, Toronto, to expose large audiences to Jawa-style video.

Later, through experiments with the size and scale of presentation, the number of viewers, and the volume and clarity of sound, we discovered that the Jawa experience was enhanced when treated in a spectacular setting. The viewing becomes like a religious event with multitudes facing the one focal point, responding together and exponentially multiplying and reinforcing the stimulation. The experience seems more powerful because it’s shared. In an interesting way, this kind of video becomes a superego magnification of the personality of the artists, replacing things we’ve lost: the rock star, the pulpit/priest—sending a message to a large group of people simultaneously (see Figure 3).

The inspiration for speed, violence and the aesthetics of a new, immediate, modern ideal was found in the Italian Futurists. One major point of dissent would be that the futurists had an anti-feminist ideal, whereas Jawa rejects the importance of any identity in the work. It is more interested in the ethereal nature of recordings, that their use is more about ideas and with them flesh and gender become irrelevant. Through the anonymity of appropriated clips, Jawa attempts to eliminate reference to identity or gender and work strictly within archetypes of masculine/feminine and myths of popular culture. It is a pursuit of universal symbols and reactions.

THE TECHNIQUE

Amongst people who have practiced the style over time there is a confirmed development: the ability to perceive minute details is increased vastly. They start to perceive moments that pass for other people. Their vision, perception and consciousness are raised by microediting for long periods of time. Furthermore, the mode of observing recordings of all kinds is no longer passive. All material becomes raw source to be absorbed and processed.

The act of editing in Jawa style is akin to a meditation; the concentrated focus of attention and analysis required to achieve the details is painstaking. If you make a mistake by one frame, you risk losing all of your work. The rhythm will be lost. The process requires you to collapse your sense of time. An hour of work may equal 10, 20 or 30 seconds of video—so, you have to collapse your sense of time and scale to those tiny fractions of moments that you’re working in. When you’ve completed a section and play back your work, you become your own audience who disjointedly experiences it for the first time.

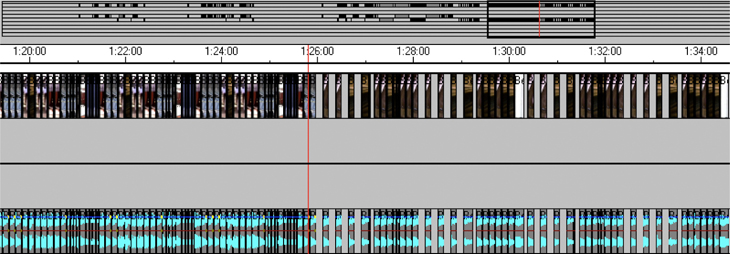

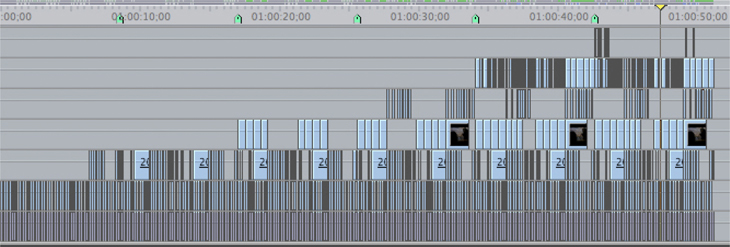

Fig. 4: This timeline contains a layer of blank placeholders, each of which is 4 frames in length. This layer can be used as a guideline. Although this screen is taken from Final Cut Pro, the technique can be performed in any timeline based editor. Early Jawa edits were single layer, straight cuts using primitive editors like DDclip, as seen in the above image.

Fig. 4: This timeline contains a layer of blank placeholders, each of which is 4 frames in length. This layer can be used as a guideline. Although this screen is taken from Final Cut Pro, the technique can be performed in any timeline based editor. Early Jawa edits were single layer, straight cuts using primitive editors like DDclip, as seen in the above image.

You will know it is working if you evoke that sensation of the now, in spite of the fact that you can anticipate what’s coming. Because the process hobbles you, it doesn’t let you have the precognition of what the piece will be. The struggle between locating the needed source, with usable video and audio, and your intent is constant. Sometimes the image works but the sound doesn’t, and you have to discard everything and start over. You are forcing things together that don’t easily integrate.

Your freedom of expression is further constrained by the technology, which imposes a slow distillation process. Instead of building up to something we’ve already anticipated, you find your vision is quickly made subservient to the source material at hand. You are left to work in stumbling steps, cajoling these factors and obstacles into something like what you imagined, although the execution will never be exact to your mental picture.

Working with the puzzle pieces, while each piece is unknown you can trust that they will interlock if you follow the strict frame-counting technique.

Jawa was founded in North America using NTSC video with 29.97 frames per second and 640x480 resolution. So, the Jawa cut-up method relies on edits or jump cuts every 4 frames, or a multiple of that. When edits are made at the 2 or 1 frame point, they must be used in groupings that equal the same length as a 4-frame cut (e.g., two 2s or four 1s). To slow the tempo, edits can be made by multiplying four–every 8th, 16th, or 32nd frame (see Figure 4).

Melodies can be made by sampling single notes from films or taking an object that has a tone, like a siren or an animal or human voice, and pitching (speed adjustment) the sample up or down. Finished samples or clips should always fit within the four-frame count.

In summary, Jawa began as a violent reaction to the misuse of video as a literal, narrative, identity focused and time-based medium. Fast, rhythmic edits of sex and violence, both catered to and encouraged the dissipation of the attention span of its audience. Today, Jawa video seeks to transform and re-contextualize mainstream media. It has evolved into audio-visual musical and composited layers in which the clips are the source of both what is seen and heard. The sound track is now and always will be the image track.

* Revised 2008, and edited by Elenore Chesnutt. This is an overview of the Jawa style of video, including amendments and revisions to the original concept, as stated in the first manifesto of 1997 by Tasman Richardson. For more information, visit www.tasmanrichardson.com

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tasman Richardson is a Canadian video artist, electronic composer, designer, curator, and organizer. For over a decade he has exhibited or performed extensively throughout the Americas, Europe, North Africa, and Asia. His work focuses on tele-presence, appropriation, synesthesia, and JAWA editing (of which he is the founder). His artworks are available through Vtape, Art Metropole, V-Atak, and his website. He lives in Toronto.

INCITE Journal of Experimental Media

Counter-Archive